Before breakfast I went down to the hotel’s deserted lounge area and signed on to the Internet. Yes! Michigan had beaten Northwestern 42-24 by outscoring the Wildcats 28-0 in the second half. Rockhurst, however, lost to Jeff City 35-33 in two overtimes. The Hawklets were without Jordan Walker, the running back who rushed for four hundred yards (!) in Rockhurst’s first game.

I consulted the forecast for Positano on weather.com. It said that it would be in the sixties this day and the next with little chance of rain. Rainer told me, however, that there was a 50 percent chance of rain in Paestum.

I ate breakfast with Ed Zieve. Just as I arrived, Charlotte left the table to return to her room and pack. I tried the coffee instead of the cappuccino, and this was a very wise choice.Ed was surprised to learn that water buffalo rather than bison were the main attraction of the buffalo farm that we were scheduled to visit. As usual, he had a story ready.

Years ago Ed and Charlotte had attended races in Indonesia in which a pair of buffalo pulled one person who was riding in some kind of contraption. Ed courageously volunteered to try his hand at it. He fell off the first time and got covered in muck. Undaunted, he got back on his chariot and managed to finish the course. They awarded him a booby prize, which consisted of a roll of locally produced cloth. He removed the cloth from the roll and wrapped himself in it to maintain his bella figura.

During this story I kept waiting for Ed to ask me if I had ever been to Shug Indonesian coutry,[1] but he never did.Sue managed to get downstairs in time to wolf down a little breakfast before the entire group assembled in the hotel’s courtyard at 8:15. From there we hiked up to the spot in the new town where the bus was parked. Sue got winded and had to stop once or twice, but she made it. Others also had trouble managing the climb up the stairs.

The plan for the day was to motor westward all the way across Basilicata and Campania to the town of Capaccio-Paestum, where we would visit a water buffalo farm and the ruins of Paestum. Giulio would then drive us up the shore to the Amalfi coast. We would then head past Sorrento to our home base for the next two nights in Positano.On the bus Rainer told us about the proprietor of the Locanda di San Martino, Antonio, a lawyer,[2] and his American wife Dorothy, who was a Professor of Anthropology (or maybe Archeology). She was in Turin for a new teaching assignment. Evidently she sometimes talks with the group about their experience in trying to adapt to life in the Sassi. Rainer filled us in on some of the details.

In the eighties the couple bought a dwelling in the Sasso Barisano and fixed it up. The process was very difficult because water and utilities were not available. Eventually the town tore up the little street that we had traversed to get to the hotel and laid pipe and cables. After the area became inhabitable Antonio and Dorothy began inviting their friends and family to visit them, and everyone seemed to enjoyed staying in the Sasso. So, the couple began acquiring additional adjacent properties to be converted into guest lodging.In the 1990’s they turned their properties into a hotel. Rick Steves’ tours, which began coming to Matera in 2004, began staying at the Locanda di San Martino, which was reportedly much nicer than the hotel previously used, five years later. The lounge area of the hotel had been used as a bomb shelter in World War II.

I tried to work on the computer on the bus, but I was unsuccessful. The road was too curvy, and there was too much glare.

Rainer decided to give us another history lesson on the bus. In the period from 1943 to 1945 Italy was bombed into ruins. In 1940 Mussolini had made the “Pact of Steel” with Hitler. Italy tried to invade Greece, but the Greeks repulsed the attempt. Italian troops had a little more success in Africa, but the heavy cost that was paid produced little or no perceptible benefit. In the eventful year of 1943 Mussolini was thrown out of office, Italy surrendered to the allies, Germany promptly invaded the peninsula, and then the allied bombing campaign was initiated.

In the same year the allies landed in Sicily. The mainland invasion started with the landings at Salerno and Anzio. The Americans inched their way up the west coast. The British and Commonwealth troops had an easier time in the east.A very bloody battle ensued at Montecassino,[3] which was the site of the German stronghold blocking the way to Rome. The Polish troops were exceptionally heroic in the battle to drive the Germans off of the hill.

The Americans liberated Rome on June 4, 1944. The Germans repositioned themselves in the “Gothic Line” along the Po River.There are two American cemeteries in Italy and dozens of British/Commonwealth cemeteries.

Rainer told us of one instance in which thirty-three German soldiers were killed by partisans in an ambush. In retaliation the Germans rounded up 330 or more Italians and executed them. The Germans had spread the word that their policy was to kill ten Italians for each German who was killed by partisans.

After the war came the golden age of Italian cinema. Most of the famous directors used the technique of Neorealism. Roberto Rossellini shot a trilogy of films about the war. Rome, Open City told the story of the liberation of Rome from the Italian perspective. Paisà was a set of six short tales about the allied advance. The third film, Germany, Year Zero depicted the fall of Berlin from the German perspective.Our route took us from the arid region of Basilicata west of Matera toward the modern-looking town of Potenza, at which point we took a short break. Thereafter, hills and mountains dominated the landscape until we got close to the agricultural regions of coastal Campania.

In the 1960’s women in Italy were not allowed much freedom. Few jobs were open to them, and divorce was illegal. In the ensuing decades, the Italian family structure had undergone drastic changes. Now some families had two working parents. Day care was starting, but most of the care of children was provided by the grandparents. “Badanti,” i.e., foreigners who provide care, were hired by some people to maintain their homes.Berlusconi’s government[4] had been cutting subsidies for education. Previously a good cheap education was considered a right for anyone who could pass the exams. College tuition was only a couple of hundred dollars per year. In recent years the children stayed home even after graduating from college. The sons seemed to stay especially close to their mothers.

Over the last few decades the government had every so often granted amnesty to immigrants who could establish that they had resided in the country for a specified number of years. One of the parties in Berlusconi’s coalition was vehemently opposed to all forms of immigration.Health care has traditionally been provided for everyone in Italy, a legacy of the Catholic Church. Abortion was legalized in the 1970’s. Berlusconi tried to impose severe restrictions on it, but he was unsuccessful.

In 1938 the Fascist government signed the Lateran Treaty with Pope Pius XI. The Italian government paid the Church a huge sum in reparations for the land seized during the Risorgimento in the nineteenth century. The government also agreed to the Church’s demand to prohibit divorce. An astonishing 90 percent of Italians claimed to be Catholics, but only 25-30 percent attended services regularly.Water buffalo were brought to southern Italy from India. They thrived in the hot swampy climate that they found in Campania. Unfortunately the malarial mosquitoes also thrived, so the government had to drain the swamps.[5]

We drove through the town of Capaccio-Paestum and in a minute or two reached our destination, Tenuta Vannulo, which we learned was a totally organic buffalo farm that was only five minutes from the ancient ruins of Paestum. I expected to see water buffalo wallowing in the mud; boy, was I ever mistaken. Although the farm did not not export anything, and it did not even sell through stores, it was extremely modern. The results of its high-tech approach to a traditional product were of such high quality that people were content to journey there to purchase mozzarella straight from the buffalo’s teat. Our hostess and guide, Stefania[6] (accent on the second syllable), explained that the milk from the buffalo did not need to be pasteurized because the operation was so carefully controlled by computers. The process started every day at around four in the morning.She explained to us how the curd was placed in very hot water and then very cold water, or maybe vice-versa. While she was talking, some men in white uniforms were working with the cheese inside a building. We were outdoors looking at them through a glass window. After the cheese was removed from the bath, it was shaped by hand, stretched into long rope-like pieces, and then actually braided. This seemed like a bizarre and fascinating thing to do with fresh cheese.

The cheese should be eaten as soon as possible after this process has been completed. If necessary, it should be stored at room temperature, but in any case it does not keep for more than three or four days.

Mozzarella, we learned, comes from the word mozzare, which means “to cut.”After the cheese-making demonstration, Stefania led us over to the building that housed the three hundred buffalo cows. They seemed to have a relatively comfortable life, all things considered. They did not seem crowded at all, and their quarters were exceptionally clean. They were furnished with sleeping areas and relaxation areas. There was even a machine that gave them massages.

I looked everywhere for a jacuzzi, but I did not see one.

The cows entered the milking area on their own accord – no one herded them or led them! The machine told them when they had been sufficiently milked. It knew which cow it was milking because of a chip which had been embedded in the animal. The cows were almost completely free from contact with humans!The cows generally produced milk for about fifteen years. Then they were sent to the butcher. This also provided a second source of income to the Tenuta, which had hired a designer whose name was, I think, Mr. Ricci, to design handbags and the like. Two people worked in the leather goods shop. The prices, however, were a little out of my league. All of the pieces that I glanced at were three-digits. I saw one price tag that was more than €400, and I did not look at very many prices. Fortunately for me (I guess), Sue is much more into quantity than quality.

A fantastic lunch was served in a lovely little setting. I sat between Sue and David Jones. David was very interested in what I knew about the very early Church. He said that he thought that the fourth-century historian Eusebius had been the first person to write that Peter was the Bishop of Rome. I told him that the oldest extant list of the popes was from Ireneus. I later looked it up in Appendix 1 of my book, and it turned out that Dave was right. Neither surviving version of Ireneus’s list included Peter.

I can usually squeeze an obscure reference to one of the popes into almost any conversation, but I never thought that I would get the opportunity to discuss this topic on one of these trips.

Lunch started with bread. There were two kinds – plain and a loaf that was stuffed with olives and anchovies. Since hardly anyone else at our table liked anchovies, I got to make a pig of myself. They also served both kinds of water and a white wine called Fiano from Alfonso Rotolo, a nearby winemaker.

The prospect of touring Paestum did not excite me at all. There were three Greek temples that were pretty well-preserved amidst the very clear outlines of a Roman town. I could not claim, however, to be fascinated by the differences between classical Doric architecture and more ancient types.

Sue and I started walking through the self-guided tour that the guidebook recommended, but she soon ran out of gas and wandered around on her own. I walked through the entire area and did my duty by taking photos of just about everything.Then I crossed the street to the museum and looked at some examples of the vases and votive offerings. It was quite warm in the museum, and I was thankful to find a chair. I saw Frank at one point, and it appeared to me that he was close to his boiling point. What would the museum have been like if it had been as hot as it had been only a week earlier?

The tomb with the frescoes of the diving person was somewhat interesting, and a few of the other frescoes were worthy a photo or two.

The view of the mountains out the back window of the museum was impressive. Aside from that, the biggest attraction of the museum were the chairs in a small auditorium.Rainer had purchased the tickets for all of us. Admission to the grounds cost €10. The museum cost another four. I am not such a student of architecture that I would have spent half that much for this experience. On the other hand, it was not nearly as big a ripoff as the Ara Pacis in Rome.

Needless to say, the shops offered souvenirs of every stripe. A statue of Totò, the Italian answer to Charlie Chaplin, who also wrote the famous song “Malafemmina” caught my eye, but I kept my money belt inside my pants.

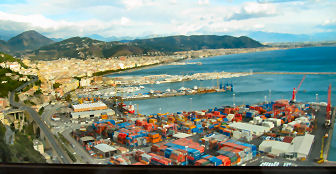

The wind really picked up while we were in Paestum. The sky was clearing, but it seemed to be getting colder as we boarded the bus for the drive to Positano. If we had been seagulls, this would have been a short trip, but the Amalfi Coast was not easily accessible by road. We had to drive almost to Naples and then double back through Sorrento.

As the bus rounded the Bay of Naples, the view was absolutely spectacular. Rainer told us that he had never seen such a crisp view of Naples splayed out at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius. The wind had cleared out the haze and smog that usually obscured the vista. I wished that I had claimed one of the seats in the front of the bus for this leg of the journey.

Rainer told us that an evacuation plan had been developed for an eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The scientists reportedly believe that they will have a twenty-seven day advance warning.

Any casual visitor to this area could not help but think, however, that when (not if) the mountain blows, the casualties would certainly be in the tens of thousands at the very least.

Many gardens and hothouses were visible on the right side of the bus in the heavily populated area between Paestum and the Amalfi Coast. I took some shots, but bus photography is very challenging under the best of circumstances.

Rainer informed us that by the year 900 Amalfi had joined Genova, Venice, and Pisa as the four rich maritime city-states. It hit its zenith in the twelfth century and went into decline thereafter. In 1343 the coast was hit with a massive tsunami and four years later the Black Plague[8] struck. It has been estimated that one-half to two thirds of the Italian population was wiped out by the plague.

I had no plan for the upcoming day in Positano, so I asked Rainer if it were feasible to make it to Vesuvius and back from Positano. He said that it was possible, but one would need to start early. I looked up in the guidebook what that would entail:

- Take the SITA bus from Positano to Sorrento. This might be a little tricky since the only road in Positano is one-way, and it does not go towards Sorrento.

- Take the Circumvesuviana train to Herculaneum, a forty-five minute ride.

- Take the Vesuviana Mobilità bus to Vesuvius.

- Climb to the peak, which takes twenty to thirty minutes. Then do everything in reverse.

I decided not to attempt this because our supper in Positano was scheduled to begin at 6 p.m., and I lacked confidence in my ability to figure out all of these different public transportation systems under time pressure. I remembered vividly how I had wasted one hour and fifty minutes waiting for the train in Viterbo because I had misread the schedule.

The drive to Positano ended along the famously scenic Amalfi Coast, but, since Sue and I had taken this same ride all the way to Amalfi eight years earlier, for us a bit of the bloom was off of the rose.

Rainer assigned us to room 408 of the Albergo Savoia. Giulio parked the bus at the top of Viale Pasitea (which at some point became Viale Cristoforo Colombo), which was as close as he could get to Positano proper. The entire group all came down in two vans supplied by the hotel. If Patti and Tom had been with us, they might have had to ride on the roof.

You had to register to use the Internet at this hotel. They told Sue to come back twice before they consented to give her instructions on how to sign on. This was both puzzling and very annoying even though Rainer had warned us about it.

At 7:30 Rainer led us on a walk down to the beach. As we left, I could swear that I heard someone asked whether the beach was downhill from the hotel. Maybe it was one of the Horenkamps; in Vieste they had appeared confused by the concept of a beach.Sue’s knees had considerable trouble with the steep slope of the pedestrian path, which was appropriately called Via Mulini. The two of us ended up abandoning the group and coming back to the room before we reached the beach. On the way we stopped at the “Delikatessen” and purchased some cheese, salami, and chips. When we arrived at our hotel room, we ate our cookies and crackers with the stuff from the Deli and washed it down with the last of the Frascati wine that Sue had been toting around for a week.

The instructions stated that the name of the Internet connection was Net Gear. We could not get either computer to find it in our hotel room. We carried our computers around to every corner, and they located plenty of networks, but they could not find the hotel’s network. Sue tried calling the desk for help. The phone rang a few times, and then it stopped ringing. Eventually Sue made it down to the first floor (not the ground floor), the site of the breakfast room, lounge, and bar, which was the only place that the Internet worked. She learned from her e-mails that the Corcorans had made it back to the States, and Patti had been admitted to St. Francis Hospital in Hartford. That was a relief.I did a quick inventory of my clothes and determine that I needed to wash a few pairs of socks, some underwear, and a shirt or two.

Overall, this had been a pretty good day. The scenery was great, the farm was very interesting, and the lunch was delicious. I could not, however, understand why the tour had taken this bizarre detour into Positano, and I did not have a thing planned for the upcoming day. I took my nightly shower and went to sleep.

[1] This is a reference to a hilarious bit by W.C. Fields in the underrated movie Mississippi.

[2] A lawyer in Italy is called an avvocato. There is another related professional, the notaio, that has no parallel in America. These extremely highly paid individuals are in charge of making sure that legal transactions are executed correctly. I have read that Italy has more laws than any other country.

[3] Montecassino is often spelled as two words. The abbey on the hill there was the home base of St. Benedict himself, the founder of the Benedictine order in the sixth century. The abbey was almost destroyed by allied bombing runs. Our bus passed by the hill in 2003, and I could not imagine anyone assailing it from the ground.

[4] The government fell on November 12, 2011. The new President of the Council was Mario Monti, an economist.

[5] Production of mozzarella from water buffalo is found only in Campania and southern Lazio. Originally this must have been because of the swampy landscape. However, now that the process has been almost completely automated, I do not see why it could not be implemented virtually anywhere that people were willing to pay for fresh cheese.

[6] It was a little brisk, but the temperatures were in the fifties and it was sunny. Nevertheless, Stefania wore a thick scarf around her neck. We had learned in the Village Italy tour in 2005 that Italians take great precautions about exposing their necks to the cold in order to prevent an ailment called cervicale.