Chapter 4: Forging the Holy Roman Empire

Gregory’s Legacy: The Church Militant

Another tribe of Arian Christians, the Lombards, descended into Italy from the north and seized control of northern Italy in 568. The next September they overran Milan. By 572 they had conquered south-central Italy. The empire controlled only a corridor between Ravenna and Rome and scattered outposts. In 579 the Lombards besieged Rome. The siege was broken, but then things deteriorated.The Church was guided through the worst of this period by its second “great” pope, Gregory I, who reigned from 590 to 604. He was a brilliant hard-working guy who never shrank from any challenge. Born into the aristocracy, he forfeited all his worldly goods to become a monk. He always seemed to be the most competent person in every endeavor. In 590 he was elected pope against his expressed will. He even voiced the hope that the emperor would reject him,[1] but after his consecration, he threw himself into the job with boundless energy.

The Lombards dominated the lands north and south of Rome from coast to coast. Several of their kings had made no secret of their wish to unite their two territories at the expense of the pseudo-Papal State that owed its existence to imperial neglect. Because of the Church’s access to a great deal of productive land in Sicily, Sardinia, and other places not controlled by the Lombards, the pope proved uniquely capable of providing sustenance to the fifty to one hundred thousand Roman citizens.

Gregory’s reforms began with a sort of clergy-ocrasy. All lay employees working in the Lateran Palace were replaced with priests. The “rectors” and “defensors” – the men who ran the pope’s estates – were likewise replaced with clergy. These moves quickly rooted out long-standing corruption and greatly improved efficiency.Gregory fervently supported the concept of a Christian empire. He seemed to regard the emperor in Constantinople and the exarch in Ravenna as God’s representatives in all things secular. He tried not to interfere with the imperial government in civil matters. He never hesitated to plead insistently for aid from the empire, and not just for defense against the Lombards. He expected the imperial government to help him suppress schismatic and heretical notions and even to enforce discipline among the clergy. When the empire failed him, Gregory sprang into action. In 592 he designated a tribune to assume command of Naples’s garrison. Stretching his spiritual authority to encompass military appointments in another city was a momentous act. When the Lombards threatened Rome, Gregory negotiated directly with them. Several times when the exarch seemed too lackadaisical about the situation, Gregory was on the verge of making a separate peace. Little by little, despite the fact that he never attempted to raise an army, the pope became the de facto ruler of all Italy not subject to the Lombards.

Gregory reportedly was the first bishop of Rome whom the emperor referred to as “the pope.” Previously Constantinople had recognized the claims of eastern patriarchs as equivalent or nearly equivalent to those of the Bishop of Rome.Pope Gregory undertook significant negotiations with the Frankish kings. He markedly influenced the development of the Church in France. A century and a half elapsed before this investment paid handsome dividends. Gregory sewed the seeds; his successors reaped the harvest.

Gregory was as unflinching in opposing heresy as any predecessor. He devoted considerable time and effort to promoting conformity to the Roman line on all theological issues. He even made inroads into converting the Lombards away from Arianism. He was fortunate to be contemporaneous with Theodelinda, the queen of the Lombards. Unlike her two husbands, King Authari and King Agilulf, she was an orthodox Christian who promoted papal missions in the Lombard territories. By the end of the seventh century – long after Gregory’s passing – the nation had been converted.Wait a minute. The entire Lombard nation was converted? One at a time? By the sheer force of the true faith? Sister Mary Immaculata now and then mentioned mass conversions, and we often prayed for the conversion of Russia, but she never explained the precise circumstances. Pope Gregory definitely employed persuasion and missionary zeal; he sent out missionaries to much of western Europe, including the British isles, and they enjoyed great success. He was never reluctant to seek help from rulers, and their aid sometimes included force, maybe even deadly force.

The use of force to inculcate Christian doctrine into unreceptive minds is a familiar concept to alumni of twentieth century parochial schools. A favorite topic of reminiscence is comparison of enhanced interrogation techniques administered by their respective teachers. However, this approach to proselytizing might seem outre to post-Enlightenment readers not privy to such an upbringing. How did the concept become so prevalent – no one seriously challenged it for centuries – that the Church had the right to condone, recommend, and sometimes even demand the use of force by civilian authorities in order to convert people to the Christian faith or to suppress ideas deemed heretical? Some context might help. Pope Gregory believed that the emperor and all civilian rulers received their authority from God. The Church, headed by the See of Rome, determined what was required to spread the Word of God. In Pope Gregory’s mind, the civilian authority’s primary role was to implement the Church’s decisions, and he expected them to do so unquestioningly. In return he willingly granted the government free rein (short of actual sin) in non-religious matters.Eradicating heresy had been one of the Church’s highest priorities for centuries. The notion that people should be free to believe and worship as they chose – a hallmark of the pagan empire! – would seem absurd to Gregory. His reasoning was something like this:

• There is one true faith. All others are heretical.• People who spread heretical views can obstruct conversions to Christianity and might delude Christians into losing their faith.

• People without faith are doomed to eternal damnation.

• Failure to stop the heretics results in people being damned to hell for all eternity.

• Such high stakes justify virtually any measure.

This delineation helps reconcile two seemingly dissonant facts: Pope Gregory condoned the use of force against heretics, but he opposed the forced conversions of the Jews. The Jews were certainly damned according to the above reasoning, but unlike the heretics they seldom openly competed for the minds of present and future Christians.[2] The Jews more or less minded their own business.

In Pope Gregory’s pontificate the papacy became an estimable political force. Necessity forced the role on him, but subsequent popes came to relish the exercise of power. Gregory concentrated authority in the hands of the clergy. He condoned the use of violence against people whose only offense was what they thought and said. In 600 the pope still had almost no direct power and exerted only limited influence on those who wielded it. Later popes, however, would be less inhibited. Clairvoyance is not required to foresee where this might lead.

Is Purgatory Only in Colorado?

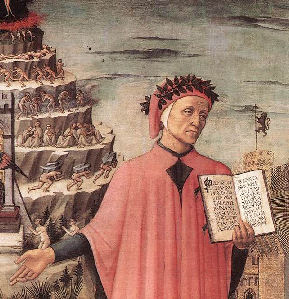

Anyone who ever occupied a desk in a classroom like Sr. Mary Immaculata’s will probably be shocked to learn that the Bible never mentions purgatory. Not only is the word absent; there is no reference to the concept itself in even an oblique manner.

If your skull has not had the concept of purgatory hammered into it, you might benefit from a primer on the topic. S’ter explained the two levels of sin,[3] mortal and venial, to us. If a baptized Christian dies with even one unforgiven mortal sin, he/she is damned to hell for all eternity. Period. However, if only venial sins stain the soul, the sinner will eventually enter heaven. First, however, the taint must be removed. Since the soul is purged by the punishment, the “place” in which the ordeal occurs is called “purgatory.”

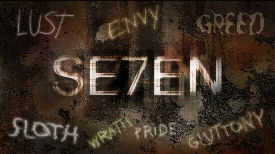

How does one determine whether the sins are mortal or venial? There are some official guidelines[4] for this, and Gregory got the ball rolling by naming seven deadly sins: pride, avarice, envy, wrath, lust, gluttony, and sloth.[5] Here is what Sr. Mary Immaculata taught about the distinction between mortal and venial sin: Best not to worry about it; avoid all “near occasion of sin,” wear your scapular,[6] confess regularly, and assure yourself life everlasting.Purgatory is a critically important concept to a Church preaching salvation and damnation. Without it there would be no middle ground; when a person died, he would be consigned to heaven or hell. Sr. Mary Immaculata and all of her predecessors taught that no one can enter heaven in a state of sin. The Church would therefore find itself forced to defend the concept that any person dying with even one unconfessed parking ticket would be doomed to hell for all eternity. A rational person might judge the probability of dying in an utterly blameless state to be so low that risk-benefit analysis would dictate that efforts directed toward achieving such perfection were futile. To put it succinctly: A guy might as well go for the gusto if those irrepressible thoughts about his mother-in-law are going to damn him to fire and brimstone anyway.

Purgatory, on the other hand, provides an incentive to avoid big sins and to limit the little ones even if one reckons that the chance of dying in a state of grace, i.e., altogether free of unforgiven sin, is slim. The Church fathers, among whom were brilliant men who ceaselessly ruminated on this subject, must have recognized purgatory’s importance at a very early stage.Gregory the Great did not invent purgatory, but he was as responsible as anyone for integrating it into Church doctrine. In the fourth book of his Dialogues he explicated its official scriptural basis. The first and most important reference is to Matthew 12:32: “he which speaketh blasphemy against the Holy Ghost, that it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come.” The gist of Gregory’s point is that if the author of Matthew’s gospel emphasized that blasphemy against the Holy Ghost is not forgiven in the world to come, then there must exist some sins that will be forgiven only in the world to come. Otherwise, why mention it? In Gregory’s words, “For if forgiveness of sins is refused for some particular sin, we conclude logically that it is granted for others.”

Uh, no. In fact, that is not within spitting distance of logical. Substitute this statement: “There is no way that the pope would allow disco music in church, whether the mass was celebrated on earth or on Jupiter.” If someone you trusted said this, would you interpret it to mean that some other type of music would be allowed on Jupiter but not on earth? Of course not. Gregory’s reasoning would be ridiculed in the first month of the first semester of Logic 101. Clearly it is possible – and in fact it is a well-known rhetorical device – to add a second outrageous condition to emphasize the impossibility of the main condition. So, a rather obvious interpretation of Matthew’s verse is that it emphasizes the seriousness of blaspheming against the Holy Ghost. Gregory also cited 2 Corinthians 3:12-15: “Now if anyone builds on this foundationGregory never advanced the idea of purgatory much beyond encouraging people to pray for the dead. However, as subsequent popes gazed on those gigantic crossed keys reserved for the See of Rome, tricky applications of the concept materialized in their heads.

The Donation of Constantine

Pepin amassed support for Stephen’s cause from other Frankish nobles. He spelled out in writing which territories rightly belonged to the pope and emphasized his intent to reclaim them for him. Embassies were then sent to the Lombard king, Aistulf. Pepin demanded that the Lombards cede the territories in Italy surrounding the corridor between Rome and Ravenna. King Aistulf was unreceptive. In the summer of 754, therefore, Pepin, with Pope Stephen beside him, marched into Italy to force Aistulf to surrender those lands. The Franks defeated the Lombards, and Aistulf was forced to submit to Pepin’s terms. Pepin then returned to France.

Once the Franks had departed Italy, Aistulf reneged on the agreement and again placed Rome under siege. Pope Stephen appealed to Pepin, and in 756 the Frankish king invaded Italy anew. Again he decisively defeated the Lombards. This time Pepin forced Aistulf to concede Ravenna and twenty other cities to “St. Peter” himself. Since the apostle himself was seldom seen in the eighth century, the keys to each of the cities and a new deed of gift were deposited on his traditional tomb in the Vatican. Thus, the papacy suddenly became a political power in Italy. Pepin made it clear to both the Lombards and the Byzantines that these were papal territories and that the Frankish kings had sworn to enforce the pope’s perpetual sovereignty.

So, how did Stephen persuade King Pepin to do so much for him? Ah, therein lies a tale worth telling. Set the Wayback Machine for 324, Sherman.Here we find the great emperor Constantine exhausted from the string of battlefield successes that consolidated his authority. He had directly witnessed the power of the Christian faith as demonstrated by his saintly mother Helena, and it inspired him. Then disaster struck; the emperor somehow contracted leprosy, the horrible maiming malady with neither cure nor effective treatment. But the emperor was a man of faith. The great saints Peter and Paul appeared to him in a dream and counseled him: “Since thou hast placed a term to thy vices, and hast abhorred the pouring forth of innocent blood, we are sent by Christ the Lord our God to give to thee a plan for recovering thy health. Hear, therefore, our warning, and do what we indicate to thee. Sylvester – the bishop of the city of Rome – on Mount Serapte, fleeing thy persecutions, cherishes the darkness with his clergy in the caverns of the rocks. This one, when thou shalt have led him to thyself, will himself show thee a pool of piety; in which, when he shall have dipped thee for the third time, all that strength of the leprosy will desert thee. And, when this shall have been done, make this return to thy Savior, that by thy order through the whole world the churches may be restored. Purify thyself, moreover, in this way, that, leaving all the superstition of idols, thou do adore and cherish the living and true God—who is alone and true—and that thou attain to the doing of His will.”

Constantine, who could state the doctrine of the Trinity with admirable clarity and precision, somehow got the notion that Peter and Paul were divine. When he questioned Sylvester about them, Pope Sly explained that they were not gods but apostles. Furthermore, the emperor’s leprosy resulted from sins he committed as a pagan. The pope insisted that absolution required that Constantine remain in his Lateran Palace dressed in a hair shirt and engaged in “vigils, fasts, and tears, and prayers.” After this penitential period Sylvester administered the holy sacrament of baptism to the emperor. Constantine felt the unmistakable power of the Holy Ghost issue from the baptismal font. The waters washed away not only his sins but also the unclean leprosy. He emerged as a whole man, spiritually and physically renewed.The emperor became convinced that God had personally invested in St. Peter and in each successive bishop of Rome, as the “universal pontiff” and “universal pope,” the “very wonderful and glorious” power to bind and loose on earth and thereafter in heaven. So convinced was Constantine of this divinely endowed authority that he ceded his imperial sovereignty to it in these inspired words: “to the extent of our earthly imperial power, we decree that his holy Roman Church shall be honored with veneration; and that, more than our empire and earthly throne, the most sacred seat of St. Peter shall be gloriously exalted; we giving to it the imperial power, and dignity of glory, and vigor and honor.

“And we ordain and decree that he shall have the supremacy as well over the four chief seats Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople and Jerusalem, as also over all the churches of God in the whole world. And he who for the time being shall be pontiff of that holy Roman church shall be more exalted than, and chief over, all the priests of the whole world; and, according to his judgment, everything which is to be provided for the service of God or the stability of the faith of the Christians is to be administered. It is indeed just, that there the holy law should have the seat of its rule where the founder of holy laws, our Savior, told St. Peter to take the chair of the apostleship; where also, sustaining the cross, he blissfully took the cup of death and appeared as imitator of his Lord and Master; and that there the people should bend their necks at the confession of Christ's name, where their teacher, St. Paul the apostle, extending his neck for Christ, was crowned with martyrdom.”

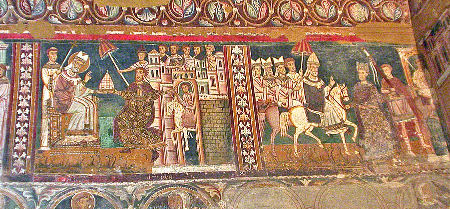

That all would recognize Sylvester as the true emperor of these lands, Constantine gave him “a diadem, that is, the crown of our head, and at the same time the tiara; and, also, the shoulder band, that is, the collar that usually surrounds our imperial neck; and also the purple mantle, and crimson tunic, and all the imperial raiment; and the same rank as those presiding over the imperial cavalry; conferring also the imperial scepters, and, at the same time, the spears and standards; also the banners and different imperial ornaments, and all the advantage of our high imperial position, and the glory of our power.”

Constantine then performed what would then have been an unthinkable act of humiliation: “holding the bridle of his (Sylvester’s) horse, out of reverence for St. Peter we performed for him the duty of groom.”[9] In order to emphasize His Holiness’s sovereignty, he moved his own retinue to the boondocks of Constantinople and built his own capital in a pale imitation of the pope’s city.To Pepin’s ears this must have seemed such a marvelous revelation that he devoted his life to enforcing Constantine’s decrees. Defeating Aistulf was only the first step. He and his son Charlemagne eventually routed the Lombards and claimed most of central Italy for the “Papal State.” It wasn’t precisely “Judea, Greece, Asia, Thrace, Africa and Italy and the various islands,” but it was enough to make the pope the most powerful man on the peninsula, a position that he would maintain for most of the next eleven centuries.

The only discordant note is that the whole tale was a crock. Nearly every word was an outrageous fabrication; it contains almost as many anachronisms as the folderol about Peter’s magic sword in the first chapter. Over the centuries the pope’s men repeatedly brandished this document to reinforce various territorial and jurisdictional claims. Indeed, for centuries after the “Donation” had been convincingly debunked by scholars, the Church still vouched for its authenticity. Precisely when all of this hogwash was gathered together over Constantine’s name into the document known as “The Donation of Constantine” is still disputed. It surfaced between 750 and 850. Pope Stephen might not have brought it with him when he trekked across the Alps to schmooze with Pepin. Charlemagne might not have read it (or had it read to him) when he became emperor forty-seven years later. Nevertheless, only believers in the tooth fairy accept that this hoax just happened to surface at the time that the Christian Franks were persuaded to assay parlous journeys into Italy in order to establish a papal state just as the pope was on the verge of losing his see to the Lombards. Even if the document itself was not fabricated until later, then at least the fictions described therein must surely have prevailed in the eighth century. Indeed, Pope Adrian I’s letter to Charlemagne in 780 mentioned donations made by Constantine to Sylvester I on the occasion of the emperor’s supposed baptism.Holy! Roman! Empire!

The commoner Leo III succeeded Pope Adrian I, scion of an ancient noble family, in 795. The Roman nobility resented Leo’s election and his conduct. In April of 799 a group that included Pope Adrian’s nephews Paschal and Campulus, who had been appointed to high offices by their uncle, waylaid a procession led by Pope Leo and assaulted him. “Some of the bystanders declared that they had seen the bandits tear out his tongue and eyes. The legend vouched for by the pope himself was added that St. Peter by a miracle restored them both the next night.”[10] The dissidents then deposed him and incarcerated him, but Pope Leo’s own supporters rescued him. He then fled to Paderborn in Germany and sought Charlemagne’s protection. The king provided an armed escort for the pope’s return to Rome. The Roman nobles also turned to Charlemagne. They accused the pope of adultery and other heinous crimes, and Charlemagne evidently took them seriously. In December of 800 he traveled to Rome to oversee the resolution of the conflict. Pope Leo asked the bishops to sit in judgment on the case, but they all demurred. Small wonder; if they came down on the wrong side of this issue, they might blow a really good gig and find themselves at the none-too-tender mercies of one side or the other. In those days “getting medieval on” someone was de rigueur. Charlemagne allegedly ordered 4,500 Saxons beheaded in one day. Pope Leo’s oath that he was innocent of all charges satisfied Charlemagne. He arrested the accusers and intended to execute them. Leo stayed his hand and instead proposed exile as their punishment. On Christmas Day in 800 Pope Leo crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor. Charlemagne’s contemporary biographer insisted that the act surprised the monarch and that he would have protested the pope’s plan. Charlemagne probably already considered himself emperor, in fact if not in name; after all, he ruled most of western Europe. The coronation officially confirmed the Church’s recognition that God had chosen him and his family to rule for all eternity. Charlemagne took the responsibility seriously. He made all of the important decisions in western Europe, even the nominally religious ones. He decreed that the practice of tithing to the Church the income from all lands would be enforced throughout the empire. He established schools in a world that had forgotten learning. He, not the pope, standardized the liturgy.The popes had gained the assurance of Charlemagne’s protection of the Papal States. They could act as monarchs of those territories without incurring the expense and the danger – most coups, after all, are led by generals – of maintaining a standing army. Moreover, Leo’s coronation of Charlemagne set a powerful precedent by establishing the papacy’s authority to crown (and therefore withhold the crown from) the emperor. Future popes jealously protected this power. Sometimes they could enforce their selections; sometimes they went with the flow; in other cases, the emperor asserted the authority to appoint the pope. If the emperor was in Rome at the right time and had his army with him, he was usually successful. Some emperors even deposed popes who displeased them; others reinstated deposed popes.

Thus began a long period in which the papacy became increasingly political and decreasingly religious. In some ways the course of events thrust this upon the pontiffs, but many choices were deliberate. No hint of this – forged papal documents, one pope beaten up by another’s relatives, a pope on trial for adultery before a king, emperors selecting popes and vice-versa – was discussed in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s classes.

For those keeping score, Pope Leo III is a saint. Charlemagne, despite his five mistresses and heaps of headless corpses, was beatified by a court bishop shortly after his death. Although he was never canonized, his veneration as a saint in a few locations has long been tolerated by the Church. Historians have mixed opinions of Pope Stephen. Trivulzio called him a great pope. Gelmi, on the other hand, said that he was devoid of scruples, that he began all the political intrigues, and that he was a catastrophe for the Church. He has never been canonized.

[1] Evidently Gregory was in this instance on the receiving end of the trickery. He wrote a letter to the emperor encouraging him to reject his election, but the Governor of Rome intercepted the missive.

[2] Except, of course, for Madonna’s.

[3] The third type of sin, original sin, is not applicable to the discussion of purgatory.

[4] They are pretty vague. For example, it has to be a “grave matter.” Pretty nearly everyone agrees that murder, in more ways than one, is a grave matter, but beyond that opinions differ greatly.

[5] L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, published a new list on March 10, 2008: polluting, genetic engineering, being obscenely rich, drug dealing, abortion, pedophilia, and causing social injustice.

[6] Chapter 13 relates the strange tale of Pope John XXII and the brown scapular.

[7]

A somewhat clearer statement is in 2 Maccabees 12:46: “Therefore he

[8] A pope named Stephen had a three-day pontificate in 752. Some lists included him; some did not. Subsequent popes named Stephen are often assigned two different numbers with one in parentheses. There have only been nine (ten) Pope Stephens, and most are forgettable. Pope Stephen VI (VII), however, was a doozy ( Chapter 5).

[9] The Latin word is strator. This rite became a part of the papal investiture ceremony, and it was performed off and on for over one thousand years.

[10] Johann Heinrich Kurtz, Church History, translated by John Macpherson, Funk & Wagnalls, 1989, p. 487. Could they have employed rubber knives? Cormenin insisted that the assailants used their nails and teeth.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Pope Gregory I wrote a letter to the emperor asking him to reject his election, but the Governor of Rome intercepted it.

$ Pope Gregory I authorized the use of force against heretics but not against Jews.

$ Purgatory, a core concept in the Church’s teaching, is nowhere mentioned in the Bible.

$ Pope Leo III was attacked by a band of thugs hired by disgruntled Roman nobles. Using knives they allegedly attempted to cut off his tongue and gouge out his eyes. Leo miraculously recovered both his vision and his speech overnight.

$ Pope Leo III was tried for adultery and other crimes. Charlemagne absolved him.

$ The “Donation of Constantine,” the document on which the popes based their claims to sovereignty in Italy and elsewhere, was a flagrant forgery.

$ Charlemagne reportedly ordered the beheading of 4,500 Saxons in one day.

$ Charlemagne, not the clergy, rewrote the Christian liturgy.