Chapter 15: The Pope is Back!

Greek Pizza, Hold the Basel

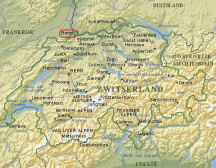

The papacy’s tussle with the clergy outlasted Pope Martin V’s passing in 1431. The cardinals again tried the “prenuptial” trick on Martin’s successor, Gabriello Condulmaro, the nephew[1] of Gregory XII, the last pope of the Roman obedience. Before the conclave Condulmaro pledged to share revenues with the cardinals, follow the council’s decrees, consult with the cardinals in administrative matters, and implement reforms. Once he became Pope Eugene IV, contrary policies seemed preferable. The conclaves’ demands for capitulations have enjoyed approximately the same success rate as Bullwinkle’s attempts to pull a rabbit out of his hat. The Council of Basel (also spelled Basle or Basil) did not exactly blast out of the starting blocks. It was scheduled to commence in March of 1431, but only one priest arrived on time. Cardinal Cesarini, who was scheduled to preside over the sessions, was fashionably late by six months. This council was not the usual aggregation of mitered clergy. One report stated that bishops constituted less than 5 percent of the attendees. Basel became a gathering of Church intellectuals rather than of the hierarchy that historically dominated such gatherings. Worried that the council might undermine his authority, Pope Eugene attempted a telekinesis trick known as “prorogation.” He issued a bull suspending the council in order to move it to Bologna. The attendees, however, remained in Basel and insisted upon the pope’s personal presence. They threatened to charge him with contumacy if he failed to appear within sixty days. Sometimes the magic works; this time it didn’t.Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class never heard of these conflicts. Maybe S’ter considered the vocabulary too difficult. Surely the Church’s hierarchy is unsurpassed at the use of obscure terminology. Where else would a “bull of prorogation” be met by a countercharge of “contumacy”?

Pressured by the clergy, the emperor, and the ruling class, Pope Eugene reluctantly submitted to the council’s authority and disavowed his previous bulls. He issued a new proclamation unequivocally acknowledging the legitimacy of the council from its opening, an unprecedented concession. The pope even sent legates to run the proceedings, and they were accepted. What kind of trick was this? It demeans Pope Eugene to compare it with a magician sawing someone[2] in half. It was as if the pontiff himself had entered a transparent box after handing his saw to his enemies. No, he actually let them use their own saw! Not even Houdini would have agreed to that. Pope Eugene’s showstopper requires spotlights for both the Swiss council and the pope in Italy. The pope is about to reveal what is up his sleeve even as the council begins to assume governance of the Church. But first His Holiness must deal with a severe setback on his home turf. Suspecting his predecessor’s relatives of expropriating Church funds, Eugene had ordered a search of the Colonna’s palazzo in Rome as soon as he became pope. The pope’s minions “exceeding their commission, instead of searching, plundered the palace of all its rich furniture and of everything else they thought was of value.”[3] The pope was not satisfied. “He tortured Otho, the treasurer of Pope Martin, an aged man, till he expired.”[4] Pope Martin’s palazzo was destroyed, and approximately two hundred Roman citizens were reportedly sent to the gallows. These acts by a Venetian pontiff ignited a rebellion in Rome. When papal mercenaries could no longer defend the pope, he took flight,[5] disguised in the black cowl of a Benedictine monk. Even so his exodus was discovered. As his boat crept down the Tiber to meet his ship in Ostia, it was pelted with stones flung by unhappy Romans on both sides of the river. He covered himself with a shield and eventually gained the awaiting ship. After a few stops the pope settled in the friendly confines of Florence, which was celebrating the completion of Brunelleschi’s magnificent cupollone for its huge cathedral.Could matters conceivably have been worse for Pope Eugene? He had conceded supremacy to the council in Basel. He had been evicted from his own see. All that he had going for him were his friends in high places. He was looking at a deuce and a five-spot in the hole. But he defied the odds, went all-in, got a great flop, and ended up with a straight flush.

Assistance arrived from an unexpected source. The Greeks in Constantinople, in schism from the Roman Church for almost four centuries, faced severe military pressure from the Turks. The Byzantine Empire no longer deserved the name; it struggled desperately for its very survival. In the summer of 1434 the Greeks sent two delegations to the west to discuss reunion with the western Church.[6] Their real objective was assistance against the Turks. One group approached the council at Basel. The other found the exiled pontiff residing in Bologna. The first step was to set the details for a summit of both branches of Christianity. Never pay negotiators by the hour; it took three years to determine the when and where of the next meeting. Meanwhile. both the council and the pope marketed indulgences earmarked for financing meetings with the Greeks.[7]

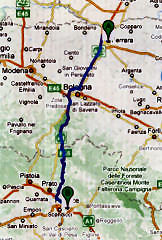

In 1437 separate embassies from the papacy and the council journeyed to Constantinople to treat with the Byzantines. In September Pope Eugene set the stage for his show-stopper. He issued a bull condemning the council for partaking in negotiations. He prorogued the council again, this time to Ferrara, a city both friendly to the papacy and convenient for the Greeks. He assured the easterners that the papal purse strings would be loosened for their visit. In January of 1438 twenty-two bishops, mostly Italians, attended the council’s opening in Ferrara.Outrage ruled in Basel. The pope’s bull was promptly declared null and void. Again the council gave him sixty days to appear. When the pope ignored its decree, the council in January of 1438 passed a resolution that suspended Pope Eugene as a simoniac, a perjurer, and a heretic. The next year a commission in Basel elected Amadeus, the Duke of Savoy, as Pope Felix V. A widower turned hermit who had fathered nine children in his first life, Pope Felix was supported by several German princes, Savoy, and many prestigious universities. Among his most trusted associates was the brilliant young Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini. [8]

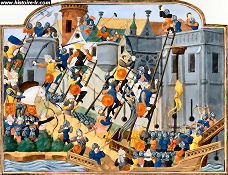

The council’s blustering availed nothing. The Greeks opted for the sea voyage and short journey to Ferrara over the transalpine trek to Basel. The synod in Basel remained in session throughout the negotiations, but over time most bishops deserted its theoretical disputations in favor of participating in the historic reunion of Christ’s Church. Eventually Frederick III, King of the Romans, sided with Pope Eugene. Piccolomini followed shortly thereafter and even became an important papal agent.In 1439 the Pope’s council moved across the Apennines to Florence. The inland location reduced the likelihood of the Greek delegation’s abrupt departure. Moreover, Florence, home of the Medicis, knew how to entertain guests. To assure their continued presence the pope paid (Byzantine) Emperor John VIII Palaeologus (who reportedly spent most of his Italian getaway on hunting trips), the Patriarch of Constantinople, and the other seven hundred or so Greek officials a generous monthly stipend. He also pledged a few ships and a few hundred men – nothing approaching a crusade – for the defense of Constantinople. Did no one savor the irony of his offer? Pope Eugene had been chased from town by dissidents throwing rocks at his rowboat, powerless even to enter his own diocese. Yet he felt no qualms about promising to defend Constantinople from the onslaught of Turkish hordes!

When Pope Eugene adjourned his council in 1445, he controlled the Church, and the conciliar movement was out-flanked, if not totally defunct. The clergy and theologians in Basel nevertheless plodded along until 1449. They were intent on implementing reforms, but that issue was so 1430’s. Pope Eugene had seized the issue of the day, reunification of the Church. Never mind that his efforts had little long-term effect. They succeeded beyond all expectations at uniting the western Church under his leadership. No subsequent council successfully contested papal authority.[9] Felix V, the last antipope of any note, respectfully submitted to Eugene’s successor, Pope Nicholas V, in 1449. He was awarded a red hat.[10] Three of his cardinals were also allowed to keep their galeri.

The Eyes Slowly Open

Pinpointing when the Italian Middle Ages yielded to the Renaissance is much more difficult than naming which pope welcomed the Renaissance to Rome. Pope Nicholas V, elected in 1447, spared no expense in restoring elegance as well as mundane items like plumbing and paving to the Eternal City. He tore down St. Peter’s dilapidated basilica and began its reconstruction. He encouraged literature, even tomes critical of the popes.[11] He financed translations of the Greek classics and was as well-read as anyone in western civilization. Piccolomini said of Pope Nicholas, “what he does not know is outside the range of human knowledge.” How did such a man get elected? He could not even claim to be a pope’s nephew. Not all was wine and roses, however. While the pope focused on edifying his capital, Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. The papal historian Platina ascribed part of the blame to the pontiff’s delay in sending already assembled troops. Pope Nicholas may have held up deployment to pressure the schismatic Greeks into reconciling with Rome. He was succeeded in 1455 by a 78-year-old Valencian named Alphonso de Borgia, who had supported his fellow Spaniard, Benedict XIII, the last pope of the Avignon obedience. Borgia ingratiated himself with Rome by helping to persuade Benedict’s successor, Clement VIII, to submit to Pope Martin V in 1429. Borgia’s papal name was Callixtus III. His pontificate contrasted sharply with his predecessor’s. Pope Callixtus thought highly of his nephews. One became governor of Castel Sant’Angelo and Duke of Spoleto. Two others he named cardinals. The 26-year-old Rodrigo[12] (also spelled Roderigo) played a leading role in the Church for five decades. This amazing fellow somehow maintained the critically important office of vice-chancellor through five consecutive pontificates. How he persuaded five popes who shared almost nothing besides a devotion to their own nephews to entrust the Church’s treasury to him remains a mystery. The Spanish pope’s urging of European princes to join forces to expel the Turks from the continent was mostly futile. He invested enormous sums, raised by massive marketing of indulgences,[13] in the construction of a papal navy that never saw action; the ships rotted away in the Tiber. Literally.Pope Callixtus arranged a retrial for Joan of Arc. The do-over found her not guilty, but the pope was powerless to commute her sentence. After her first trial in 1431, only ashes remained.

The first Borgia occupied the throne for only three years. In 1458 it seemed obvious to the conclave that it was Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini’s turn. His papal name was Pius II. Although only fifty-four, he had been a force in the Church for decades. Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia diplomatically led the “accession” by which Piccolomini’s plurality became the required two-thirds majority.Pope Pius was as intellectual as Nicholas V. He was also an accomplished writer and an inveterate diarist. Years earlier Emperor Frederick III had named him poet laureate. At the age of forty he had even written erotic stories! His youth entailed more than writing about sex. His two bastard offspring died in infancy.

Absolutely nothing about sex was ever mentioned in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class or anywhere else in our school. It was treated like a contagious disease; boys and girls were physically separated at the daily mass, at recess, and on nearly every other occasion. Students were strictly prohibited from attending co-educational social functions until eighth-grade graduation. There was whispering in the shadows, but if more was going on, my friends and I were ignorant of it. That a writer of erotic stories who had sired illegitimate children might become pope was so far off the chart as to have been incomprehensible to us. The Church figures about whom we learned were all like Catherine of Siena and Dominic Savio, completely free of impure thoughts. Although Pope Pius’s curriculum vitae would surely have shocked us, his successors made him look prudish.

When Pope Pius II needed a cardinal, he exercised his world-renowned creativity. His exhaustive search of available candidates determined that the best man was his twenty-two year-old nephew. Anyone with a few euros can view the highlights of Pope Pius’s career in the breath-taking Piccolomini Library inside the Duomo in Siena. The exhibit, which features luscious murals by Pinturicchio, was financed by this nephew. Pinturicchio somehow missed the pope’s trip in 1459 to Florence. The Florentines constructed a large cage for his benefit. “Lions were enclosed with horses, wild boars, dogs, and a giraffe to welcome Pius II.”[14] One can only imagine what transpired therein for the pope’s amusement. A mural of this event would stylishly finish off the library. Any takers?A warm corner of Pope Pius’s heart was devoted to the abbreviators, a group of scribes who saved paper by copying documents in a condensed format; essentially they developed a system of shorthand. Pope John XXII had transformed this group into a papal profit center. By the 1460’s the quality of their work had seriously deteriorated. Pius established the “College of Abbreviators.” Here is what The Catholic Encyclopedia says of them:

In the pontificate of Pius II, their number, which had been fixed at twenty-four, had overgrown to such an extent as to diminish considerably the individual remuneration, and, as a consequence, able and competent men no longer sought the office, and hence the old style of writing and expediting the Bulls was no longer used, to the great injury of justice, the interested parties, and the dignity of the Holy See. To remedy this evil and to restore the old established chancery style, the Pope selected out of the great number of the then living Abbreviators seventy, and formed them into a college of prelates, and decreed that their office should be perpetual, that certain emoluments should be attached to it, and granted certain privileges to the possessors of the same. He ordained further that some should be called “Abbreviators of the Upper Bar” (de Parco Majori), the others of the Lower Bar (de Parco Minori); that the former should sit upon a slightly raised portion of the chamber, separated from the rest of the hall or chamber by lattice work, assist the Cardinal Vice-Chancellor, subscribe the letters and have the principal part in examining, revising, and expediting the apostolic letters to be issued with the leaden seal; that the latter, however, should sit among the apostolic writers upon benches in the lower part of the chamber, and their duty was to carry the signed schedules or supplications to the prelates of the upper bar. Then one of the prelates of the upper bar made an abstract, and another prelate of the same bar revised it. Prelates of the upper bar formed a quasi-tribunal, in which as a college they decided all doubts that might arise about the form and quality of the letters, of the clauses and decrees to be adjoined to the apostolic letters, and sometimes about the payment of the emoluments and other contingencies. Their opinion about questions concerning chancery business was held in the highest estimation by all the Roman tribunals.[15]

A slightly terser explanation for all this folderol is that the college served as a sinecure for the pope’s favored literary lights.

A large deposit of alum, a sulfate used in the fabrication of paper and the dying of wool,[16] was discovered in the Papal States in the middle of Pius’s pontificate. Mining of this valuable commodity provided dependable revenues for the popes throughout the Renaissance period. Nevertheless, lack of funds often posed a real problem. “(Pope Pius II) once suffered so extreme a dearth of money that he was forced to restrict his household and himself to one meal a day!”[17]Pope Pius’s letter in 1462 to the Bishop of Ruvo declared that enslaving recently baptized Africans would be a great crime. The crime was not so much the enslavement per se as the degrading treatment of fellow Christians. The papacy never directly condemned the institution of slavery for the next five centuries.[18]

Pope Pius patched up relations among several princes of Europe. However, his call for a crusade against the Turks failed. Few Europeans evinced any interest, perhaps because of the availability of many easier ways to earn indulgences. He nevertheless felt so strongly about this project that he volunteered to lead it himself, a first for a crusade to the Holy Land. He died in Ancona awaiting the Venetian fleet’s arrival to transport the assembled crusaders. By the time that the ships finally sailed into port, the army had disbanded.

A Gem of a Pope

Pius’s successor in 1464 was Paul II, a Venetian. Although only forty-seven, he had been a cardinal for more than half of his life. His own career was plainly engineered by his uncle, Pope Eugene IV. Nevertheless, one of his first actions as pope was to outlaw nepotism, perhaps the most futile decree in papal history.

Pope Paul had sworn to convoke an ecumenical council within three years. He warmed St. Peter’s throne for eight years, but calling the council never quite made it to the top of his “to do” list. As usual, pressure from the tiara on the papal cranium repressed memories of commitments to limit pontifical power. One might think of Paul II as the first metrosexual pope, or something like that. He loved the highest quality clothes of the latest fashion. His thing about jewels went way beyond adorning his outfits with lustrous baubles. He had a backup papal tiara made to order. Both crowns were studded with precious stones worth a pope’s ransom. He maintained a drawer full of sapphires. He was often observed fondling colorful jewels à la Captain Queeg. He reportedly amassed fifty-four silver chests full of pearls. Pope Paul applied makeup to bring out his best features. So vain was he about his appearance that he even considered taking the name Formosus (which means handsome or shapely) II. The ghastly fate of the corpse of the ninth-century Pope Formosus – disinterment followed by a posthumous trial, dismemberment, and ejection into the Tiber – must have given him the vapors. Under stress Pope Paul reportedly had a disconcerting habit of breaking into tears. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Feeling that ordinary Romans could profit from a little more color in their humdrum existences, Pope Paul restored the pagan elements of the Carnival (Mardi Gras) celebration – images of gods and mythical characters such as nymphs and satyrs. He also staged a track meet (in February!) with separate divisions for seniors and Jews.[19] Animals joined in the fun; horses, donkeys, and buffalo all had events. His Holiness presided over the festivities from the balcony of his recently constructed residence, Palazzo San Marco (now called Palazzo di Venezia), whence he tossed coins to the multitude. What a pleasant way to get in the mood for Lent! Pope Paul had disdain for his predecessor. He quickly eliminated the College of Abbreviators. Since practically all literati of the period belonged to this organization, this act insured abominable press[20] for Pope Paul. He had arrested an abbreviator called Platina and charged him with paganism, sodomy, and attempted assassination. Everyone considered the charges bogus, but Platina was imprisoned and tortured anyway. However, the writer outlived the pontiff, and the next pope placed him in charge of the Vatican Library. When Platina was asked to update the official papal history, his treatment of Pope Paul was not exactly flattering. In 1466 Pope Paul II called for a crusade against George of Podebrady, the King of Bohemia, whose sympathies with the Hussites were not to the pontiff’s taste. “The tens of thousands who responded to the bloody summons of the assumed ‘Vicar of Christ,’ were for the most part, an undisciplined rabble, the scum of Germany, with vagabond reprobates and mercenaries from all parts of Europe.”[21] The king put this motley assemblage to rout. The number of defenders was reported less than the number of papal troops they captured.Platina reported that in 1471 Pope Paul expired suddenly in a fit after dining on some melons. It could happen.

The Renaissance Uncle

Many historians date the official commencement of the Rinascimento, the Italian Renaissance, to the election of Francesco della Rovere as Pope Sixtus IV in 1471. Few realize that a famous Vatican building bears his name. Italians don’t like the sound of the letter X, so they call the pope’s magnum opus “Cappella Sistina”, the Sistine Chapel.In several important ways the new pope was a true Renaissance man. He built up the Vatican library and instigated the construction and decoration of his chapel, although Michelangelo’s frescoes came later. He continued and even accelerated the modernization and beautification of the city of fountains. His taste was beyond reproach.

Even the pontiff’s most critical biographers carefully note that Pope Sixtus was very attentive to religious ceremony. He performed every ritual and function with punctilious respect and devotion.

There. I did it: three entire paragraphs about the legendary Pope Sixtus IV without using the word “nephew.” Someone should contact Ripley’s, for Sixtus raised the bar for papal nepotism to a level never previously contemplated. His nephews were key players even before he became pope. His sister’s son,[22] Peter Riario, was also his campaign manager in the conclave. A humble Franciscan monk[23] in his mid-twenties, Peter assured the cardinals that Uncle Francesco would not forget them after he assumed the tiara.Pope Sixtus certainly remembered his own family. He made cardinals out of five nephews and a grandnephew. He rewarded Peter’s yeoman’s work in the conclave with a few well-paying positions: Bishop of Treviso, Cardinal Archbishop of Seville, Patriarch of Constantinople, Archbishop of Valencia, Archbishop of Florence, and Bishop of Spoleto. That Peter actually visited these dioceses before he died two years later is unlikely; after all, Seville and Constantinople are not exactly neighbors. Another nephew, Julian della Rovere, a couple of years Peter’s senior, was appointed Archbishop of Avignon, Archbishop of Bologna, and bishop of the following dioceses: Lausanne, Constance, Viviers, Ostia, and Velletri. He was also named the head man at a few abbeys. Domenico della Rovere had to wait a few years before becoming a cardinal. Meanwhile he contented himself with the bishoprics of Corneto, Tarentaise, Geneva, and Turin. The grandnephew, Raphael Sansoni Riario, received his red hat when he was only seventeen years old. Every male member of the pope’s large family received valuable fiefdoms or benefices.

All Della Rovere family members held advanced degrees in the art of high living. Peter Riario’s was summa cum laude. Despite the obscene income from his benefices, he died deeply in debt only two years after becoming a cardinal. He insisted on traveling with a retinue of one hundred horsemen. His tastes were lavish, and his mistresses were “high maintenance.” De Rosa wrote that he had chamber pots made from gold. Pope Sixtus provided the cash to support such lifestyles. Not since $crooge McPope, the legendary John XXII, had Holy Mother Church been blessed with such imaginative financial wizardry. Brothels were a big business in Rome in the 1470’s, employing approximately seven thousand out of the fewer than fifty thousand Romans. Licensing these entrepreneurs allowed the Holy Father to tax them. He also set sales record for collagia, permission slips for the supposedly celibate clergymen to satisfy their need to breed. Laymen could purchase similar dispensations when they determined that certain matrons with absent husbands required solace. For centuries one pope after another had sold bone fragments of the early Roman Christians to churches[24] and to pilgrims. Unfortunately, these remains were not an easily renewable quantity. The bones could be chopped up into ever tinier pieces, but inevitably the supply of such fragments became depleted. By the fifteenth-century the Church faced a severe shortage of relics, and it was affecting the bottom line. Having obtained his doctorate from the University of Pavia, Pope Sixtus understood that the Treasury of sanctifying grace amassed by the good works of Jesus and the saints qualified as a boundless asset. This Treasury had for four centuries been tapped for indulgences for crusades or pilgrimages and eventually for financial support for papal causes. The pontiff checked the Treasury’s balance sheet and gleefully discovered that all these indulgences had hardly dented it.Having only one soul each, Christians previously had little incentive to earn more than one plenary indulgence. However, most had numerous deceased friends and relatives, and many of the most lovable were sinners who died without a plenary indulgence. Pope Sixtus’s brilliant scheme allowed Christians to earn indulgences for the dead. When he authorized indulgence transfers, demand just skyrocketed. After the pope relaxed the association with crusades and elaborate pilgrimages, Rome’s revenue stream flowed much more reliably than its aqueducts.

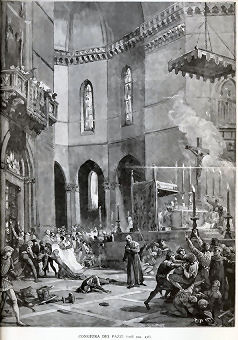

Since 1400 the Medici family of Florence had functioned as papal bankers. They grew as rich as the Rockefellers and had consistently been shrewd enough to support the papacy. In Pope Eugene IV’s darkest hour, for example, the Medici princes financed the wining and dining of the Byzantines attending the council of Ferrara-Florence. However, when one of Pope Sixtus’s nephews opened an account at the First Medici Bank and Trust to deposit a month’s indulgence sales, the teller neglected to offer him the customary free toaster. The cardinal reported the slight to the pope. His Holiness indignantly shifted the Church’s accounts to the bank run by the rival Pazzi family. When Philip de’ Medici, the Archbishop of Pisa, died in 1474, the pope designated Francesco di Bernardo Salviati to succeed him. Lorenzo de’ Medici, who expected his brother Julian to succeed Philip, was so upset at Salviati’s appointment that for three years he prevented him from entering his see. The absentee archbishop conspired with Francesco de’ Pazzi and Giovanni Battista da Montesecco, the captain of the papal mercenaries, to remove Lorenzo and Julian from the scene and to overthrow the Republic of Florence. They planned to assassinate the Medici brothers during mass in the cathedral.[25] If Pope Sixtus did not specifically order the assassinations, he evidently knew the details of the plot. Montesecco felt a little squeamish about committing murder in church, so he hired two less scrupulous priests to do the deed on April 26, 1478. At the consecration of the Eucharist the dagger-wielding padres fell upon the unsuspecting Medicis. Julian perished from multiple stab wounds. Lorenzo was also wounded; he wrapped his cloak around his arm and used it as a shield as he retreated to the sacristy. Evidently no one had apprised the teen-aged cardinal, Raphael Riario, of the plot. As he witnessed the sacrilegious spectacle, his complexion turned an ashen grey, and it allegedly never recovered its normal shade.The Florentines were not amused. Pazzi, Archbishop Salviati and his brother, and others involved in the plot were guests of honor at a necktie party thrown in the Piazza della Signoria. The assassin-priests had their ears and noses amputated before they too were executed. Montesecco lost the top foot or so of his physique to the executioner’s axe. Raphael, a cardinal and grandnephew of the pope, was imprisoned as an accomplice.

In the fifteenth century no one incarcerated the pope’s kin. Sixtus retrieved a large X-bomb from the armory and placed the entire city of Florence under interdict. He ordered his in-law, Ferrante, the King of Naples, to bring Florence to heel. However, Lorenzo de’ Medici himself journeyed to Naples and persuaded Ferrante to abandon the pope’s cause. Naples even allied itself with Florence, France, and Venice. Meanwhile, the Turks had made their first sally onto the Italian peninsula and seized the city of Otranto! Pope Sixtus removed the interdict on Florence and forgave Lorenzo’s insubordination. In 1481 a unified Christian response forced the Turks to abandon their Italian toehold. Nobody expected the Spanish Inquisition seven years later, but Pope Sixtus authorized it. Perhaps he hoped to postpone the onset of the Little Ice Age by augmenting the supply of atmospheric carbon dioxide. In one year in Andalusia alone two thousand people were burned to death as heretics.Sixtus IV enjoyed an excellent relationship with his vice-chancellor, Rodrigo Borgia, who was ordained a priest during this pontificate. On October 1, 1480, the pope expressed his thanks for Borgia’s service by granting Caesar (also written Cesare)[26] Borgia, the cardinal’s six-year-old son, dispensation from the requirement of proving that his birth was legitimate. Without the dispensation Caesar could never become a cardinal. What a comment upon the fifteenth-century Church that powerful prelates laid the groundwork for their bastards’ clerical careers before they reached the second grade! Two years later young Caesar was granted the revenues from the prebendals and canonries of Valencia and was appointed canon of the same see. In his tenth year he also became the provost of Alba and the treasurer of the Church of Carthage.

[1] Or perhaps the son. Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 117.

[2] A once-in-a-lifetime variation on this trick produced an incredible effect. “Gasps and screams were heard in the audience. Many people fainted. Others fled the theater.” Ricky Jay, Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women, Warner Books, 1986, p. 71.

[3] Archibald Bower, The History of the Popes From the Foundation of the See of Rome to the Present Time, 1766, part 7, p. 239.

[4] Milman, op. cit., Vol. IX, p. 336.

[5] Philip Schaff reckoned that Eugene was the twenty-sixth pope forced to flee from his diocese. Only one subsequent pope, Pius IX, suffered this humiliation, and that was four centuries later.

[6] “Western” is appropriate; there was little Roman about the Church in 1434.

[7] Henry Charles Lea, A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences, Philadelphia, 1896, Vol. II, pp. 179-180.

[8] The accent in his last name goes on the middle syllable. The lyrics of a clever song consist solely of this name repeated over and over with the emphasis on different syllables.

[9] Of course the revolutions of the Protestants would soon provide challenge enough.

[10] He was also allowed to wear all the vestments and insignias of the papacy except the Ring of the Fisherman and the cross on his slippers. The pope was even required to rise from his seat and salute him with a kiss when they met.

[11] Rest assured that this attitude was short-lived. Even in the twenty-first century nearly all books soft-pedal criticism of even the most outrageous pontiffs.

[12] Rodrigo Borgia is considered the first “cardinal-nephew,” the young man charged with managing the details of the papacy. From 1555 to 1691 every pope but one appointed a cardinal-nephew in an official brief.

[13] “At his command legions of monks spread themselves through the different kingdoms of Europe, … laid the inhabitants under exactions, sold to them indulgences and absolutions, and drew from them such enormous sums that the cellars of the Vatican were none too large to accommodate them.” Cormenin, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 128.

[14] The Papacy, an Encyclopedia, 1958, Vol. I, p. 58.

[15] The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. I, p. 29.

[16] You can also use it to write a message on a hard-boiled egg through its shell. The trick is explained at http://www.wackyuses.com/experiments/secretmessageegg.htm. Amaze your friends.

[17] Leopold Von Ranke, History of the Popes: Their Church and State, translated by E. Fowler, 1901, Vol. I, p. 277.

[18] John T. Noonan, Jr., “Development in Moral Doctrine,” Theological Studies 54 (December 1993), p. 675.

[19] This detail would have fascinated Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class. Some might have fixated on the dissonant notion of the Vicar of Christ introducing pagan images into a Christian festival. A wise guy might have posed the following theological question: If the Second Coming had occurred during Pope Paul’s pontificate, could Jesus have competed in the senior division, or would he be required to race against his fellow Jews?

[20] The printing press had been invented around 1445. By Pope Paul’s time there was something vaguely resembling a press in Italy.

[21] “A Papal Retrospect,” The Dublin University Magazine, Vol, LXXXVI., July to December, 1875, p. 237.

[22] Peter Riario was also widely considered to have been the pope’s son.

[23] De Rosa has claimed that as a monk Peter Riario baked his habit once a year to rid it of vermin.

[24] In 787 the Council of Nicea mandated that relics of saints be placed in the altar stone of every altar in every Catholic church in the world.

[25] Many authors assume that the cathedral was the familiar Duomo of Santa Maria Del Fiore, but Machiavelli, who should have known, placed the assassination in the old cathedral of Santa Reparata.

[26] He is also often called Valentino, which refers either to the family’s home town of Valencia in Spain or to the title that the King of France gave him, Duc de Valentinois.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Immediately after his election, Pope Eugene IV dispatched men to the palace of the family of his predecessor. They plundered everything of value. The pope then ordered Otho, the Church’s treasurer, tortured. He did not survive the ordeal.

$ Pope Eugene IV had to disguise himself to escape from Rome. As he left he was pelted with stones by angry Romans.

$ Pope Pius II wrote erotic stories when he was forty. He also fathered two children out of wedlock.

$ Pope Paul II was a fashion horse and used makeup. He had a huge collection of gems and pearls, which he loved to fondle.

$ Pope Paul II added pagan touches to the Carnival celebration

$ Pope Paul II hired a bunch of thugs as mercenaries in order to invade Bohemia. The papal army was routed.

$ Pope Paul II died in a fit after dining on some melons.

$ Pope Sixtus IV made cardinals out of five of his nephews as well as one grandnephew.

$ Pope Sixtus IV was privy to the semi-successful plot to murder the Medici brothers in the cathedral in Florence. The assassins were priests.

$ Pope Sixtus IV licensed the prostitutes of Rome.

$ Pope Sixtus IV expanded the market for collagia, permission slips for celibate clergy to have sex, to include laymen looking for guilt-free sex outside of marriage.

$ Under Pope Sixtus IV indulgences earned by the living could be applied to the dead.

$ Pope Sixtus IV exempted Caesar Borgia from proving that his birth was legitimate.