Police work for the Army at SBNM. Continue reading

I don’t recall much about my first couple of weeks patrolling the base and standing guard duty alongside the other members of the second platoon. I remember that whenever I had to stand guard duty I listened to an FM station on the radio that I had purchased. The good reception was another unexpected benefit of being so close to a major city. When I was at the main gate I made up license numbers to record in the log that no one ever examined. The other two gates got much less traffic. I don’t think that we bothered with logs. The gates may have been locked at night.

Almost no one entered or exited through the east gate for the simple reason that there was nothing beyond the east gate except the scrub land that the natives called (mistakenly, according to Webster) “mesa”. If someone approached from the west you could see them coming when they were still several minutes away.

I have retained a couple of memories of being on patrol with more experienced guys. Once I remarked to my partner that I was disappointed that I had not seen a roadrunner. He quickly responded, “There’s one, and there’s one on the other side of the road.”

I have retained a couple of memories of being on patrol with more experienced guys. Once I remarked to my partner that I was disappointed that I had not seen a roadrunner. He quickly responded, “There’s one, and there’s one on the other side of the road.”

As a cartoon aficionado I naturally expected roadrunners to be about the same size as coyotes. They are actually are only about eighteen inches from tail to beak, and a very skinny tail takes up a good portion of that. Furthermore, the ones that hung around our base never had much need to demonstrate their speed.

One guy in our platoon was really short. He was a big Black guy from KC who was scheduled to ETS a few weeks after we arrived. He had already decided to reup, and he requested an assignment in Vietnam. He had already completed one tour there, and he told me that he knew how to make a lot of money there selling drugs. I would say that there was at least a 50-50 chance that he was putting me on, maybe even baiting me. I don’t know why he would have confided to a complete stranger a plan for illegal activity.

He was the only guy in the barracks who had a television in his room. I asked him where he got it. He told me the name of a discount department store near the base. He showed me a clipboard that he had. He claimed that he walked into the store, checked the packing slip on a box for a TV against a piece of paper on his clipboard, picked up the box, put it confidently on his shoulder, and walked out. Once again 50-50, but the clipboard idea could have other applications. I bought one at the BX.

He was the only guy in the barracks who had a television in his room. I asked him where he got it. He told me the name of a discount department store near the base. He showed me a clipboard that he had. He claimed that he walked into the store, checked the packing slip on a box for a TV against a piece of paper on his clipboard, picked up the box, put it confidently on his shoulder, and walked out. Once again 50-50, but the clipboard idea could have other applications. I bought one at the BX.

The only other thing that I remember about him is that he really liked Sly and the Family Stone.

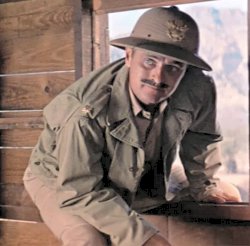

The guys that guarded the gates and patrolled the base wore OD fatigues, but the trousers were starched, pressed, and bloused below the knees. The boots and belt buckle had to be polished. In Basic they had made us remove the plastic coating on the brass belt buckle. At SBNM most guys bought a new belt and left the coating on to prevent tarnishing. Some guys even bought patent-leather boots to eliminate the need for shining. They also wore their holsters, armbands, and white MP hats. Indoors the hats were ALWAYS removed. If it was cold, they wore gloves and field jackets. Hands were NEVER allowed in pockets. Of course, if no one was looking, …

I vividly recall one midnight shift that Russ Eakle and I were parked in one of his favorite hiding places near the Officers Club. He had already given a couple of citations for rolling through the stop sign at the end of the club’s driveway. The club was a good distance from any activity. There was seldom any traffic in either direction, and if there had been, the headlights would have been visible a mile away—literally.

Russ returned to the truck in a bad mood. He said that the officers whom he had ticketed had complained that it was petty for him to issue a ticket. “They should show respect for the badge,” said Russ I made some semi-commiserating noises without mentioning the fact that we did not have badges, just armbands. We then resumed our position again in anticipation of more vehicular crimes. Soon an erratically driven vehicle appeared. The driver was a naval officer with salad on his epaulets. Sitting in the passenger seat was a much younger woman. The car hardly slowed for the stop sign.

Russ turned on the siren and the cherry-top and pulled the vehicle over. He got out of the truck and did his Duke-walk toward the offending vehicle. Russ conversed with the driver for about ten minutes. When he returned to our truck I asked him what he charged the guy with. He said that he let him off with a warning because he had been very polite and respectful.

I am quite sure that he was polite and respectful. He was probably afraid that he was going to be written up for driving under the influence, and the police report would probably include the name of the passenger. DUI is a serious offense. Even a ticket for rolling through a stop sign might cause him trouble with his superiors, and he might have a lot of explaining to do to his wife as well.

Russ never did get it. His approach punished people for trivial offenses and allowed those guilty of more serious things to grovel their way out of it. It disgusted me.

I really hated being on patrol, especially with Russ. I did not see how if I could put up with it for the 19+ months that I had left in my hitch. Fortunately I did not need to.

Before we went on duty for the swing shift we lined up in the courtyard behind the PMO for a “guardmount”, an inspection by an officer. Part of the routine was to make sure that nobody’s .45 was already loaded before the clip was inserted. One at a time we would draw our .45 and pull back the slide on the top. The officer would then look inside from the top to make sure there was no bullet in the chamber. He then said “Clear!”, and the guy with the .45 would pull the trigger to return the slide to the forward position.

One time Lt. Hall, second-in-command of the MP Company, was inspecting our patrol. When he had finished examining Al Williams’ pistol, he shouted “Clear!” Al pulled the trigger and his .45 fired. The bullet actually shot the hat off of Lt. Hall’s head! It was mostly the lieutenant’s fault; he apparently didn’t bother to look in A.J.’s .45 very carefully. We all just pretended that nothing happened.

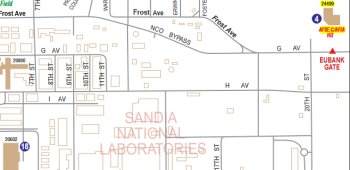

Manzano Base was mostly located underground beneath the mountains in the lower right. Below the mountains is a mileage indicator. The arrow in the top left indicates the main part of SBNM.

One time I was assigned to spend a midnight shift on guard duty at Manzano Base. This assignment was peculiar in two ways. 1) Several miles from anything resembling civilization, it was by far the most desolate and boring assignment. The visible part of the base was surrounded by two high fences, one of which was electrified. By the time that the midnight shift started, no one else was in the facility; at least that was the case on the night that I was there. 2) The entire base was top secret. No one seemed to know what went on there. A top secret clearance was required for the guard that MPCO SBNM supplied at night. The thing was, my clearance had not arrived yet.

The duty itself was not very memorable. In fact, nothing at all happened other than intermittent buzzing sounds from the base. To stay awake I took a few walks around the perimeter of the parking lot gazing at the starlit sky and singing cowboy songs at the top of my voice: “Some boys they go ridin’ the trails just for pleasure …”

The duty itself was not very memorable. In fact, nothing at all happened other than intermittent buzzing sounds from the base. To stay awake I took a few walks around the perimeter of the parking lot gazing at the starlit sky and singing cowboy songs at the top of my voice: “Some boys they go ridin’ the trails just for pleasure …”

I was disappointed that no coyotes joined me. There were lots of roadrunners around here; there must be coyotes, right?

After the shift I went to the mess hall for breakfast. I bought an Albuquerque Journal. On the front page was a story about Manzano Base. It emphasized the secretive nature of the base and the ironclad security. I considered writing a letter to the editor explaining how the reporter had missed his chance because during the night that that issue of the paper went to press Manzano had been guarded by a guy with no clearance at all. I thought better of it.

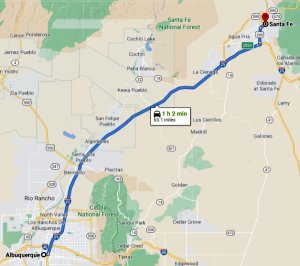

A group of us was somehow chosen to make a road trip to Santa Fe, the capital and cultural center—it has an opera company!—of New Mexico. A military funeral was being held there, and MPCO SBNM was assigned the task of providing a three-volley salute. This was a very popular duty because it offered a rare opportunity to get off the base, have a free meal at a restaurant, and see a little of Santa Fe. I don’t remember who else was in this group of eight—seven enlisted men to shoot the rifles and a sergeant to tell us when to fire. I am pretty sure that we all wore our regular fatigue uniforms with our MP armbands and white hats.

A group of us was somehow chosen to make a road trip to Santa Fe, the capital and cultural center—it has an opera company!—of New Mexico. A military funeral was being held there, and MPCO SBNM was assigned the task of providing a three-volley salute. This was a very popular duty because it offered a rare opportunity to get off the base, have a free meal at a restaurant, and see a little of Santa Fe. I don’t remember who else was in this group of eight—seven enlisted men to shoot the rifles and a sergeant to tell us when to fire. I am pretty sure that we all wore our regular fatigue uniforms with our MP armbands and white hats.

We took a van. The drive to Santa Fe was a little over sixty miles. During the first half the Sandia mountains were on the right, and the usual desert scenery was on the left. In the second half we began the climb to Santa Fe, which is 7,199 feet above sea level.

General Patton called the M1 Garand “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” Ours probably just needed cleaning.

On the way the sergeant warned us about the M1 rifles, relics from World War II. Because none of us had even seen one of them before, he had to explain how to make them work.

Evidently they were not very reliable. He said that we should not be surprised if the weapon we were holding did not fire. We should just continue with the ceremony. As long as a few of them worked, no one would know the difference.

We arrived at the cemetery only a few minutes before the start of the ceremony. We all lined up a couple of feet apart. The sergeant called the command to take aim. We pointed the rifles into the air at a 45° angle. When he yelled “Fire”, we all pulled our triggers. Four or five rifles worked, including mine. The M1 had a little more kick than an M16. On the second command, only two or three worked. Mine still functioned. The last volley consisted of only one actual shot. It was tempting for the rest of us to yell out “Bang”, but no one did.

We were all very embarrassed. We had no intention of making a mockery of the poor guy’s funeral. We hurried to our van and made a quick getaway. We did not start laughing until we were far enough away that no one could see us.

The only thing that I remember about our lunch on the road was that we all enjoyed it.

My metabolism was not designed for shift work. I had only pulled one all-nighter in four years of college, and that was when a bunch of us were working on the dorm’s homecoming float. I really need at least four or five hours of sleep per night, and it must be at night. By the second night of every midnight shift I was a zombie.

I remember an unfortunate incident at breakfast at the mess hall, which was serve cafeteria-style. They gave me the plate with my omelet, and I placed it on my tray. Then I pushed my tray down to the end and right off onto the floor. I just forgot to grab the other end with my right hand.

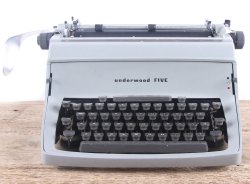

On the walk from my room to the PMO on another day I noticed a piece of paper on the bulletin board near the MP Company’s clerical office. It asked if there was anyone in the company who knew how to type. In those days typing was an uncommon skill among guys. Why should they learn how to type? The secretarial pool did that kind of thing. As I recounted here, however, I had taught myself to type in high school, and I was actually pretty proficient at it.

On the walk from my room to the PMO on another day I noticed a piece of paper on the bulletin board near the MP Company’s clerical office. It asked if there was anyone in the company who knew how to type. In those days typing was an uncommon skill among guys. Why should they learn how to type? The secretarial pool did that kind of thing. As I recounted here, however, I had taught myself to type in high school, and I was actually pretty proficient at it.

I sought out to the clerk, whose name was Orsini2, and informed him that I knew how to type. He was pleased to hear it and arranged for me to take a typing test the next day.

I was confident that I could handle a job in the military that required typing skills. However, I had never taken a typing test. I was not sure how it would be graded, and I was somewhat worried about a bad habit that I had developed. Typing books prescribe that the thumb should be used to press the space bar. I have always used my right forefinger.

Since I did not bring my typewriter to Albuquerque, I could not practice using my thumb on the space bar. Besides, you can type much faster and more accurately if you pay no attention to what your fingers are doing. A separate part of your brain knows where all the keys are. The best idea is to depend on it. So, I boldly resolved take the test using my usual deviant approach and forget about my thumb.

Since I did not bring my typewriter to Albuquerque, I could not practice using my thumb on the space bar. Besides, you can type much faster and more accurately if you pay no attention to what your fingers are doing. A separate part of your brain knows where all the keys are. The best idea is to depend on it. So, I boldly resolved take the test using my usual deviant approach and forget about my thumb.

SP4 Orsini sat me down at a typewriter3 that had some paper already loaded in it. On my left side he placed a sheet of paper that had a few paragraphs of text on it. “Aha”, I thought, “I know this trick.” I moved the paper to my right side, glanced down to make sure that my fingers were properly placed, and typed the first couple of lines. I went at a pretty good clip, and I had not made any mistakes when …

Orsini stopped me. “Thanks” he said. “That’s enough.’ The next day I was told that instead of going on patrol or gate duty, I was to report to Lorenzo Bailey, the Desk Sergeant for the second platoon. Evidently Orsini just wanted to make sure that I did not “hunt and peck”.

Orsini stopped me. “Thanks” he said. “That’s enough.’ The next day I was told that instead of going on patrol or gate duty, I was to report to Lorenzo Bailey, the Desk Sergeant for the second platoon. Evidently Orsini just wanted to make sure that I did not “hunt and peck”.

My new assignment involved a slightly different uniform. I did not carry a nightstick. The holster for my .45 was attached to a webbed belt. During all of the time that I worked on the desk I never inserted the clip in the pistol. I always kept it in my pocket. No one ever noticed that the handle was empty, or, if they did, they did not care.

The desk sergeant and his assistant(s) used the police radio to dispatch patrols to whatever required attention. Since Sgt. Bailey did not type, the assistant(s) were required to type up incident reports as well as the log of all activity for the shift. Sgt. Bailey’s assistant was Randy Kennedy, who had just been promoted to sergeant himself. Bailey (no one ever called him Lorenzo) needed another assistant because Randy was scheduled to ETS (leave the military) in a short time.

For the guys on the desk the three shifts were quite different. The day shift was almost always busy. Some civilian employees assisted us on patrol, but they were not easy to work with. They were all Mexican-Americans; several were named Gallegos, apparently relatives. They always drove the black and white sedans; they never touched the trucks. They could patrol, but we could hardly use them for anything else. I don’t think that they ever relieved anyone at a gate or escorted a “run” from the commissary or BX to the bank. We never sent them on anything that might require judgment, such as a reported crime or a traffic accident.

We had to let everyone have time for lunch. The most challenging aspect was to make sure that there was sufficient coverage during that period.

The swing shift had two busy times. There was a lot of vehicle traffic when the people from Sandia Laboratories went home between 5 and 6. Later there could be incidents at the two bars, the Officers Club and the NCO Club. Domestic disputes, everyone’s least favorite, could occur near the end of the shift.

Usually we only had two people on the desk for the midnight shifts.

The most challenging was when the ‘Officer of the Day” decided to make a nuisance of himself. At night, when the Base Commander was not readily available, an Officer of the Day was in charge of the base. This assignment rotated around all of the unmarried field-grade officers on the base—Army, Navy, and Air Force.

Most officers dreaded this duty, but one guy relished it, a naval officer named, believe it or not, Lieutenant Commander Commander. Yes, Commander was both his title and his last name; I don’t know if Commander was also his first name. However, I do know that both major (in the Army, Air Force, and Marines) and lieutenant commander (in the Navy and Coast Guard) have the same pay-grade, O-4. So, our Commander Commander had the same rank as Bob Newhart’s Major Major.

Most officers dreaded this duty, but one guy relished it, a naval officer named, believe it or not, Lieutenant Commander Commander. Yes, Commander was both his title and his last name; I don’t know if Commander was also his first name. However, I do know that both major (in the Army, Air Force, and Marines) and lieutenant commander (in the Navy and Coast Guard) have the same pay-grade, O-4. So, our Commander Commander had the same rank as Bob Newhart’s Major Major.

Commander Commander liked to inspect the gates. He would call the PMO and ask us to send a car to pick him up. This was the last thing that we wanted. Our most responsible guys were seldom assigned to gate duty, and it was best not to think about what amusements the other guys had brought with them to help kill time.

The second time that Commander Commander did this on our shift, we were ready for him. We sent Charlie Antonelli4 to escort him. Charlie was the shakiest person I have ever met. He was nervous about everything. He always was dressed and ready for duty more than a half hour early. He would then walk up and down the hall asking people if his gig line was straight and his boots were shiny enough. He was always concerned about any of the dozens of rumors that were circulating, and he constantly sought other people’s opinions about them. Charlie was a nice guy, but it did not take long for this to become annoying.

The second time that Commander Commander did this on our shift, we were ready for him. We sent Charlie Antonelli4 to escort him. Charlie was the shakiest person I have ever met. He was nervous about everything. He always was dressed and ready for duty more than a half hour early. He would then walk up and down the hall asking people if his gig line was straight and his boots were shiny enough. He was always concerned about any of the dozens of rumors that were circulating, and he constantly sought other people’s opinions about them. Charlie was a nice guy, but it did not take long for this to become annoying.

One other important fact needs emphasis. Charlie’s shakiness contributed to his standing as—by far—the worst driver in the platoon, probably the company, and maybe the whole base. Charlie was never allowed to drive a police vehicle. We always found a partner for him, and the partner always drove.

When we got the call from Commander Commander, we sent Charlie to pick up him up. I don’t remember how we got rid of Charlie’s partner. Maybe we claimed that we had a “special project” for him.

Charlie picked up Commander Commander at the Bachelor Officers Quarters (BOQ), which is where he was staying. Charlie called in on the radio and said that he was en route to the main gate with Commander. About fifteen minutes later Charlie drove his vehicle to the PMO, parked, and came inside. He told us that Commander Commander had told him to pull over to the side of the road. He said that he would walk back to the BOQ. They never even made it to the main gate. We considered it a small victory.

I did not know Randy Kennedy too well. He did not live in the barracks, and he ETSed a short time after our group arrived. However, I became pretty good friends with Sergeant Bailey. He was a lifer, but he was anything but gung ho. I don’t know how long he had been in the service, but at this point it was just a job for him.

I remember that there was an incident that happened just before I started working on the desk. I don’t remember the details of it, but Bailey was worried that he would get in a lot of trouble over it. We were working mids together, and he asked me to type his statement for him. I helped him compose it in a way that emphasized the positive aspects of his involvement. He was very appreciative. He explained that in one of his previous assignments he had been guarding a prisoner and for some reason he used the nightstick on him and caused permanent damage. He had not been punished, but a letter about the incident was in his permanent record. If he had another black mark, he could face some serious discipline. As far as I know, nothing happened to him.

By the way, Bailey was Black, and Kennedy was white. There were quite a few Black guys and some Mexican Americans in the MP Company. I never heard of any racial incidents.

I can remember a few peculiar events when I was working on the desk. Once there was a traffic accident during daylight hours only about a block away from the PMO. We had no patrol vehicles available. So, I abandoned my typewriter and walked over to handle the accident. I brought the forms with me on my clipboard, but it was a very minor incident, and the two parties agreed not to report it. Since it was our policy to give a ticket whenever there was an accident. I was pleased with this resolution.

The only time that I ever gave a ticket was the day that someone way above my pay-grade decided to set up a speed trap on Wyoming St., the main drag. So many cars were caught that they directed them over to the parking lot near the PMO, and they enlisted everyone they could find to write tickets. They only did this once.

During the day the PMO received quite a few telephone calls. Bailey answered most of them, but occasionally he was busy with something. I was required to identify myself: “Provost Marshall’s Office, Private (later specialist) Wavada speaking.” In the pursuit of plausible deniability, I practiced saying this until I could say it as fast as I could say a Hail Mary. My debate training helped. No one ever asked me to repeat my name.

Once I was called upon to investigate a reported crime. A lady called the PMO to report that someone had broken into her house. Sgt. Bailey asked me to drive one of the spare vehicles to her house and fill out a report. She told me that nothing was missing, but sh wanted to show me the door through which the intruder had allegedly entered by breaking a glass panel. There was indeed a broken pane, but the glass was on the outside of the door. It seemed unlikely to me that the miscreant had caused this as he made his escape. He certainly did not enter that way.

The guys on patrol often forgot that anyone with a police-band radio could listen to their transmissions. We had cut to short many conversations that had drifted into taboo topics with “10-21”, which told them to call us on a telephone. It was frustrating when the patrol responded with “What does 10-21 mean? I left my ten series card in my room.”

I was considered very good at typing up incidents using the various forms, especially the traffic accident reports. No brag; just fact. I had two skills that got my work noticed. 1) I could write clear, grammatical declarative sentences with accurate spelling. 2) I had perfected the skill of fitting n+1 letters into n spaces. This latter skill was invaluable. The reports had to be typed, and there could be no scratch-outs. So, if you left a letter out of a word, you had to start over. It was, however, possible to Wite-Out the erroneous word. Then I was sometimes able to key in the corrected version by partially depressing the backspace key while typing each letter so that the spaces between letters were reduced, but the word was still legible.

I was considered very good at typing up incidents using the various forms, especially the traffic accident reports. No brag; just fact. I had two skills that got my work noticed. 1) I could write clear, grammatical declarative sentences with accurate spelling. 2) I had perfected the skill of fitting n+1 letters into n spaces. This latter skill was invaluable. The reports had to be typed, and there could be no scratch-outs. So, if you left a letter out of a word, you had to start over. It was, however, possible to Wite-Out the erroneous word. Then I was sometimes able to key in the corrected version by partially depressing the backspace key while typing each letter so that the spaces between letters were reduced, but the word was still legible.

At some point in May I was removed from my duty as a desk clerk for the second platoon, Instead I started working in the Law Enforcement Office. I still lived in the same room amidst the guys in the second platoon. I don’t remember who replaced me on the police desk, but I do remember that Sgt. Bailey was not happy with this development.

By the time that I assumed my new role I had been promoted to Private First Class. This had nothing to do with my performance. Because such a long time with no new personnel had passed before the five of us arrived, MPCO SBNM had a supply of approved promotions ready to give to the first people who had enough “time in grade”. Because Ned Wilson and I had been promoted at the end of AIT, we both got promoted to PFC before the other guys in our group.

By the time that I assumed my new role I had been promoted to Private First Class. This had nothing to do with my performance. Because such a long time with no new personnel had passed before the five of us arrived, MPCO SBNM had a supply of approved promotions ready to give to the first people who had enough “time in grade”. Because Ned Wilson and I had been promoted at the end of AIT, we both got promoted to PFC before the other guys in our group.

Ned and I also got promoted to SP4 as soon as we were eligible. The number of available SP4 promotions was smaller. I don’t remember exactly when that was, but the rest of the guys had to wait some time before they achieved it. I calculated that I earned several hundred dollars extra, and I owed it all to the lie that I told my platoon sergeant before the “white glove” inspection in AIT.

Ned and I also got promoted to SP4 as soon as we were eligible. The number of available SP4 promotions was smaller. I don’t remember exactly when that was, but the rest of the guys had to wait some time before they achieved it. I calculated that I earned several hundred dollars extra, and I owed it all to the lie that I told my platoon sergeant before the “white glove” inspection in AIT.

I never met anyone at either of my two permanent duty assignments who had been promoted as fast as Ned and I were. I only know about the MPs at SBNM, but at Seneca Army Depot I had access to all the personnel files.

1. The Manzano facility was integrated into Kirtland AFB in 1971. Its function has changed, and it is no longer classified. An account of its history can be read here.

2. I did not know it at the time, but the Orsini family in Italy has produced three popes and at least ten cardinals.

3. All the typewriters that I encountered in the Army were manual models. The IBM Selectric had been around for a decade, but I never saw one until in my Army career.

4. I have no way to verify it, but I think that Charlie died in 2020, just as I was beginning this project. The obituary is here.

Pingback: 1971 SBNM March-June Part 4: The Guys in MPCO | Wavablog

Pingback: 1972 January: Transition to Seneca Army Depot | Wavablog