I am not sure when the Billion Dollar Idea began to coalesce in my brain. After the first few years of the twenty-first century it was becoming obvious to me that the rapid consolidation of the number of large retailers … Continue reading

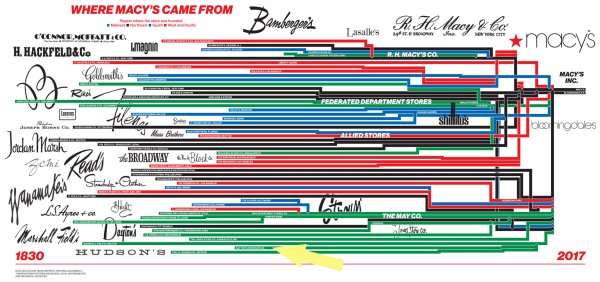

I am not sure when the Billion Dollar Idea began to coalesce in my brain. After the first few years of the twenty-first century it was becoming obvious to me that the rapid consolidation of the number of large retailers had drastically diminished the prospect for sales of the AdDept system. So, I was constantly on the lookout for ways to apply TSI’s assets in a potentially profitable manner.

Here is a list of what I thought that the company’s most valuable assets were:

- The ability to deliver high-quality custom programming expeditiously.

- The proven ability to design functional databases.

- A good understanding of all forms of advertising except for Internet advertising, which was still experimental and rapidly evolving.

- A good understanding of retail concepts.

- A growing understanding of U.S. newspapers.

The market that I had long coveted was the development of a universal database for storing medical histories. Because of the complexities involved in such a task, most software developers would shrink from it. However, even then I could see that there must be many billions of dollars at stake. Maybe TSI could claim at least a small share, which would, of course, not seem small to us. However, in order to make any sensible plans, the company would need some sort of entrée into the market. That is, we would need client #1 first, and I could not imagine how that might come about.

So, I tried to think about where we might use our knowledge of advertising and newspapers. At this point I should explain the sources of profit for newspapers. The revenue from subscriptions and single-issue sales never came close to covering the costs of newspapers. Newspapers have always relied strongly on income from advertising, which mainly came from three sources:

- Display ads within the text of the newspaper were called “ROP”1, which stood for “run of press”. These ads were billed by the amount of space used, either in pages (or fractions thereof) or in column-inches. Advertisers might pay extra for color or for prime positions, such as in the sports section or the back page of the main section.

- Classified advertising included help wanted and personal ads.

- The preprinted flyers that were stuffed into some issues of the paper were called “inserts”. They were billed by the size (number of pages or weight) and the quantity, and the distribution in thousands of copies. Some large papers allowed for selection of distribution by zip code or some other method.

Later, as their circulation numbers dropped, a third option called “polybags” was embraced by many newspapers . These were plastic bags that served as flimsy raincoats for inserts that were delivered willy-nilly to people without subscriptions.Sometimes the inserts were enclosed within an abbreviated edition of the paper that often contained news of mostly local interest.

TSI’s department store clients were almost always the largest purchaser of ROP ads in each of their newspapers. The AdDept installations had required us to learn how to handle the most complicated contracts and ROP strategies. Inserts seemed relatively simple to us. We knew almost nothing about classifieds.

One aspect of inserts struck me. They had nothing to do with the contents of the newspaper. Whereas the ROP ads had to be fitted into the spaces not taken up by news and other articles,2 the inserts were totally independent of the paper’s content and of one another. Therefore, the inserts could just as easily be delivered by any other organization with the infrastructure to do so.

The newspaper’s advantages was that it was contracted by the readers’ subscriptions to deliver the papers anyway, and so the papers incurred only minimal additional costs. The printing was done elsewhere. The inserts were just stuffed into the middle of each copy of the newspaper. For the newspaper they were almost pure profit.

On the other hand, many advertisers ran exactly same insert in a very large number of newspapers. ROP ads could be sent electronically to the papers, but the inserts needed to be physically delivered. That process must necessarily be both expensive and subject to errors.

It seemed to me that any organization that had a large number trucks and drivers in every market could potentially compete with the newspapers for the insert business provided that:

- The trucks and drivers were available every Sunday, the day that inserts were ordinarily delivered.

- The inserts could be packaged in an attractive manner so that they were bound to be opened and read.

- By minimizing the number of locations to which the advertiser must deliver, shipping costs for them could be held to a minimum.

- Key advertisers could be persuaded that they would receive both lower shipping costs and more targeted marketing for the same cost.

- A foolproof system could be devised for online ordering that would automatically do billing or Electronic Funds Transfer. To my knowledge TSI was the only company that had developed a sophisticated system for ordering of newspaper advertising.

It seemed to me that three organizations could surely meet the first four criteria: Federal Express3, United Parcel Service, and the U.S. Postal Service. Adjustments would be necessary, but all of the requirements are close to their core business. I was pretty sure that, with the proper hardware, TSI could handle the fifth item. At least I was willing to consider making such a commitment.

I thought a lot about how such a project could come into being. I would need to set up a meeting with a high-level executive at one or more of the organizations. This was a big stumbling block. Over the years I had dealt with a large number of influential people. Most of those relationships were quite good, but none of them, at least to my knowledge, had much to do with any of those organizations or any other group with a large number of trucks. I could put a letter in the mail, but when no one responded, then what?

I fantasized about getting a meeting with Fred Smith, the founder and CEO of FedEx. I had heard that as a young man he had had a difficult time persuading people of the practicality of his concept of a central hub in Memphis for deliveries all over the country. It was based on a paper that he wrote for an economics class at Yale.4 My idea—of advertisers bringing their inserts to the nearest FedEx office instead of bringing them to every newspaper—was no more off-the-wall than his had been, and he was now worth billions.

I could envision workers wearing red and blue delivering “FedExtra” packages all around the country on Sunday mornings. People would tear open the packages like Christmas presents.

If I did manage to get someone to take a meeting, I would need to make a compelling presentation. It was hard for me to figure out how I would do it. I would need to downplay the difficulty of implementing a delivery system and emphasize (1) the large amount of revenue that was potentially at stake and (2) the importance of a customized ordering system (which we had sort of developed with AxN).

I just could not visualize how I could make this work. I was confident of my abilities to assess whether a system that a potential client described could be feasibly implemented by TSI. However, in this case I had to convince the prospective client that it had the wherewithal to implement part of the system but not a critical aspect of it. If I were in their shoes, I would either dismiss the idea out of hand, or I would ask for more time and then call my IT department to see if they could handle the fifth step.

I was not even sure that I could convince anyone of the feasibility of the project. None of the groups that might be able to pull this off were accustomed to dealing with advertisers who used print media. They would need to locate the people who buy the service from the papers and convince them one at a time of the superiority of the new approach.

Someone would need to provide the capital. I certainly did not have it. I did not even have knowledge sufficient to indicate that $X of capital would be required, and it could likely be made back in Y years. That is what people generally want to hear at the first meeting.

I had a strong suspicion that the companies that distributed flyers that contained lots of manufacturers’ coupons would be key. The other companies would probably want their flyers to be in that package because that was the one that frugal buyers would seek out. We might need to give the coupon distributors a discount.

I could anticipate other difficulties as well. Both the USPS and UPS were heavily unionized. Making deliveries on Sunday would probably be a very big deal. FedEx was not as heavily unionized, but its pilots were, and this project would likely affect them a lot. I could foresee that it would provide the shipping company with a lot of business, but it might complicate its relationship with its labor force. We could be of no help in that regard.

One good aspect was that the project could be rolled out market by market. There was no need for a national launch. When the second market was launched, presumably the national advertisers from the first market would be happy to participate. Only the local advertisers would need to be recruited.

So, I put a lot of thought into this idea but no effort beyond a little research. I still think that the project could probably have been done. I needed to find a partner who had worked at a large newspaper and was familiar with both the difficulties of working with the advertisers and the difficulties involved in obtaining the flyers and assembling them. Together we might be able to construct a presentable business plan. Unfortunately, I never met such an individual and for several years I had my hands full with AxN and AdDept.

A big concern for me at the time was that, if the project succeeded in wresting the insert business away from the newspapers, many of them would go out of business, and the country would lose its major source of investigative journalism. In retrospect it seems risible that I would suppose that turning trees into pulp would always be the principal source of information for people.

When I started thinking about the project I was in my late fifties. A few years later my penchant for finding new worlds to conquer abated.

1. Although ROP is a true acronym and the periods were almost never included when it was written, I never heard anyone pronounce it as a one-syllable word. It was always called “are oh pee”.

2. On a visit to the Springfield Union News/Republican I learned that actually the papers were often laid out the other way—the ads were placed first, and the text was placed in the empty spaces that remained. The editor told me that they once had held a space open for an missing Filene’s ad that right up until the very last minute before press time.

3. I was able to locate no reliable information (both advertisers and newspapers were vague) as to how much money was spent annually on inserts. $20 billion per year was my best estimate.

4. Smith’s paper received a C. The concept must have seemed outrageous in the mid-sixties.