Finally made it to NDT! Continue reading

The U-M team in 1975-1976 was, of course, a little different from the previous year’s. Don Goldman and I still comprised the coaching staff. The team lost two debaters. Mike Kelly had graduated, and Tim Beyer had decided not to debate after his freshman year. So, Wayne Miller debated with Mitch Chyette all year, and Don Huprich debated with Stewart Mandel. Two freshmen joined the team, Dean Relkin and Bob “Basketball” Jones.1 Bob knew Don Huprich; I am not sure how Dean found out about the team.

The financial situation was even worse than in the previous year. The travel budget remained the same, but Paul Caghan was no longer around. Even if he had been, I doubt that I would again have requested a stipend for his girlfriend. Also, I had high hopes that in March Wayne and Mitch would qualify for the National Debate Tournament in Boston. We would need to find financing for that somewhere.

The debate topic for the year was “Resolved: That the federal government should adopt a comprehensive program to control land use in the United States.” Wayne and Mitch ran an affirmative case about the Army Corps of Engineers. Don and Stewart’s case was about coal pollution and solar heating/cooling. I liked the latter a lot more than the former.

In 1974-75 I had worked with Tim and Stewart Mandel primarily on strategy and the construction of individual arguments because their presentation skills had already been pretty well honed in high school. In 1975, on the other hand, I needed to devote more time with Bob and Dean to fundamentals.

Dean Relkin’s word rate per minute was without a doubt the lowest of anyone that I ever heard in an intercollegiate debate. There was never any doubt that Bob had to be the second affirmative. Almost everyone in college typed up the first affirmative constructive speech, which was then delivered word-for-word. Generally, the only exceptions were to add a joke or two that might be appreciated by the judge. The speech would ordinarily be delivered at a conversational pace—considerably slower than the other seven speeches.

The first affirmative speech that was designed for Dean could be read aloud by any of the other guys in seven or eight minutes. So, their affirmative case contained, by necessity, fewer arguments than anyone else’s. This was not necessarily a significant disadvantage. Sometimes debaters present more arguments than they can defend.

Dean had a skill that considerably helped offset his shortcoming in the speed department. He had exceptionally good word economy—the ability to state an argument in the most compact manner. In fact, the only debater whom I have ever heard with better word economy was the legendary Tom Rollins2 of Georgetown, who won the top speaker award at NDT in 1975 and then again in 1978. He was runner-up in 1976.

To address the speed problem in the other three speeches we decided that it would be best for Dean to give the first affirmative rebuttal and both second negative speeches. Most speakers giving the 1AR, a five-minute speech that follows fifteen minutes of arguments from the negative, spoke at a very rapid rate. Dean could not match them, but his phrasing was so good that he almost always was able to answer all of the 2NC arguments and also do a pretty good job of dealing with the most important points in the 1NR.

The second negative posed a different set of problems. Most of Dean’s constructive speech could be written out ahead of time, and he was fully capable of coming up with new arguments. The problem was that the 1AR might present so many answers that Dean could not get through them all in his rebuttal. So, he needed to learn how to select one or two of his best arguments against the affirmative plan and strive to win the important points supporting those points. He also needed Bob to select an argument or two that he (i.e., Bob) had presented in 1NC and defended in 1NR for Dean to “pull through” in his rebuttal. They had to practice this quite a bit, but eventually they got it down.

Bob also had a problem that was difficult to deal with. I noticed in practice debates that he would sometimes skip an argument. In a debate this is tantamount to conceding it. Doing this even once could easily turn a victory into a defeat.

All debaters took2 careful notes when the opponents were speaking on a “flow sheet” with several columns. In one column were the opponents’ arguments. In the next column were written the planned responses in shorthand. That column served as the outline for the speech.

I decided to ask Bob Jones to participate in a mini-debate. Someone would read a first affirmative speech. Bob would take notes and prepare a first negative constructive for me to listen to. Ordinarily I would also take notes on my flow sheet, but in this case I just watched Bob while the other participant read the case.

After about a minute or two I called a halt to the exercise. I noticed that Bob was holding his pen between his middle two fingers. His thumb was barely involved at all. This might be a good grip for a bear, but there are many better ways for a creatures with opposable thumbs to write. Bob’s approach forced him to lift his hand after every few characters to see what he wrote, which, considering that none of his fingertips were in contact with the pen, could be just about anything. Try it yourself!

I was flabbergasted. Aside from hiring a first-grade teacher to come to the Frieze Building to teach him how to write, I could think of no practical advice for him. I occasionally awoke in the middle of the night fretting over this problem.

I did have one unexpected visitor in the Frieze Building that year, my cousin John Cernech, Terry’s older brother. He may have called before he arrived. If not, I do not know how he found the debate office.

He told me that he was a dean at Quincy College (Quincy University since 1993) in Illinois. It was a Catholic school of a little over one thousand students. I had no idea what being a dean entailed—Animal House was not released until 1978—and did not press him about it. That he was administering a college surprised me a little. He was two or three years ahead of me in high school, and academics was not his specialty.

He might have told me about Terry. Somehow I learned that he was managing a pizza restaurant.

He was very cordial as he asked me about what I had been up to. I told him about my classes and the debate team. I may have told him about living in Plymouth and Sue; I don’t remember. It probably would have been courteous to invite him to lunch or dinner, but I didn’t. I naturally assumed that he had come to spy on me for someone in my family. I may have been mistaken.

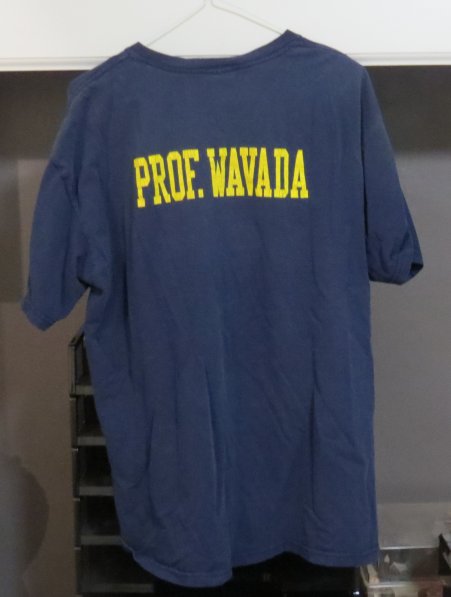

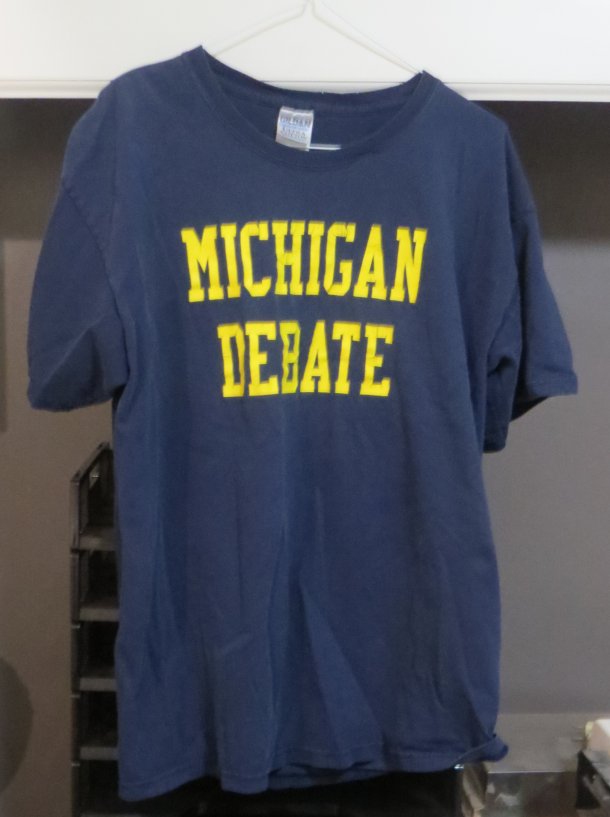

I think that this was the year that the blue Michigan Debate tee shirts appeared on the circuit. The guys still dressed nicely for the preliminary rounds, but they broke out the tee shirts for elimination rounds. “Michigan Debate” was imprinted on the front in maize; the debater’s name was on the back.

They got one made for me, too. The front of mine had a “C” to denote my status on the team. The back said “Prof. Wavada”. This was in honor of the mythical Professor Wavada (wuh VAH duh) who was often announced as a judge for elimination rounds. Of course I was not a professor. I had never even taught a class in anything anywhere.

The guys were not receptive to my idea for much snazzier uniforms. I envisioned the debaters wearing maize (the color, not the plant) shirts with blue ties arrayed with maize wolverines; these ties were on sale in Ann Arbor. Over these shirts we would wear blue blazers with the school seal emblazoned on the breast pocket. The debater could add his own name on the back in maize letters. The trousers would be a tasteful maize and blue plaid. The footwear would include maize socks and white bucks with a bold block M in blue on the toe of each shoe.

I remember changing into my tee shirt whenever I was chosen to judge an elimination round. During the very first time that I wore it the room became uncomfortably chilly. I shivered so much that it became difficult too take good notes. Nevertheless, I never covered up the school colors with a jacket.

Don Goldman escorted Bob and Dean to several nearby tournaments. I remember taking the pair to two. The first was a varsity tournament at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. The guys did a terrific job. They actually qualified for the elimination rounds. I was really proud of them.

I had learned from Dr. Colburn that Juddi and Jimmie Trent were both professors in the speech department at Miami. I looked them up. I was disappointed that I did not get to talk with Jimmie, but I did spend a little time catching up with Juddi. She did not seem to have changed much. I certainly had, at least in appearance. I wonder what she thought of the bearded cowboy with glasses that I had become.

I also drove Bob and Dean to Novice Nationals at Northwestern. Three things stand out in my memory from that tournament. At the beginning of the event David Zarefsky was master of ceremonies at an assembly. He started by directing our attention to the “continental breakfast, which you all know is a euphemism for coffee and donuts.” A few people laughed.

He then presented the tournament’s staff. One of the Northwestern coaches was female, and she was very hot. I don’t remember her name. When Zarefsky introduced her he mentioned that “she had served in every conceivable position.” I guffawed, but no one else had even the slightest reaction. It was a little embarrassing.

A unique feature of the Novice Nationals was the way that the schedule for the preliminary rounds was determined. All eight rounds were set before the tournament began. They divided the country into four geographical sections. Each team met two teams from each section. I really liked this format.

At the assembly one of Northwestern’s many coaches announced that the staff was having a contest. I don’t remember what the prize was, but they challenged the attendees to deduce the determinants of the sections. I spent a little time on this and submitted my list of teams in each section. At the final assembly they announced that there had only been one entry in the contest. They awarded me the prize and announced that I had only made one mistake. I think that I had Central Michigan and the University of Detroit in the wrong groups. The dividing line between the eastern group and the east-central group went through Ypsilanti MI.

After seven rounds Bob and Dean still had a chance to qualify for the elimination rounds. Unfortunately in the last round they faced a very good team from the University of Kentucky. Bob and Dean were on the negative. I had judged UK’s case several times, and we had plenty of time to prepare for this round.

I suggested to the guys that they should use the Emory switch in this round. That is, Dean would give his plan attacks in the first negative. Bob would analyze the advantages claimed by the affirmative in the second negative. In addition, Bob might be able to answer part of the second affirmative’s refutation of Dean’s disadvantages. Dean would have the entire five-minute 1NR to resuscitate his plan attacks. Bob would give the 2NR and pick the best arguments to sell. He had never done this speech before, but he had a lot of experience with this speech, and the mindset is similar.

The guys agreed to try it. Kentucky still won the debate, but both Bob and Dean thought that the switch gave them an enormous tactical advantage. They both thought that they would have been embarrassed if they had used their standard approach.

One of the Kentucky debaters later talked with me about the switch. She complained that the Michigan team only did that because they knew that they could not win with the usual strategy. This was, of course, true. She did not claim that the switch was illegal or unethical. She did not even argue that it was inappropriate for a novice tournament. When I asked her if Bob and Dean should have just rolled over and conceded, she just walked away.

It just occurred to me that this might have been Bob and Dean’s final debate. I wonder.

The first tournament for the four varsity debaters was again at Western Illinois. Wayne, Mitch, Don, and Stewart piled in Greenie and I drove them to Macomb. I don’t remember the details of this trip, but Wayne Miller has assured me that he and Mitch made it to the final round.

On Saturday at this tournament I must have had a round off from judging. I remember walking by myself over to Hanson Field where I watched part of a varsity football game through the chainlink fence. I don’t remember whom the Leathernecks played that day or what the score was. It wasn’t Michigan Stadium, but it was real football, and I enjoyed it.

The highlight of this tournament for Wayne Miller was not the trophy that he fondled through most of the grueling return trip. It was learning the saga of Herm the Sperm, which I related somewhere in the middle of the Land of Lincoln.

Herm was an extremely industrious sperm. He started every morning with his Daily Dozen, a set of exercises design to maximize his strength, stamina, and—above all—speed. The afternoons he spent in the pool working on his strokes. His goal was to be not just the best sperm, but the best in every stroke—butterfly, backstroke, and freestyle.

Herm had nothing but contempt for the other sperm. “Go ahead,” he told them. “Just sit there lounging around smoking cigarettes. One day, when the lights flash and the alarms sound, you’ll regret it. That’s when it will be every sperm for himself, and you just know that the first one to reach and penetrate the egg will be none other than yours truly, Herm the Sperm.”

A few of the sperm tried to emulate his devotion and energy, but they soon gave up. Herm had set the bar too high.

Then one day the lights did flash and the alarms did blare. Sure enough, Herm sped past the tens of millions of his brethren. They knew they could never pass him, but they still pressed forward. That is just what they were designed to do.

Then, to their amazement they saw Herm attempting the hopeless task of swimming against the stream. “Get back!” he cried at the top of his lungs. “Get back! It’s a blow job!”

My recollection of the rest of the tournament schedule is very spotty. Wayne and Mitch usually qualified for the elimination rounds, but they did not win any tournaments. Some of the specific recollections that I have don’t concern debating or coaching.

I remember standing with Mitch at the back of the auditorium at Emory University in Atlanta. The debate director was a formidable woman with a powerful voice, Melissa Maxcy4. Mitch could not help himself. He turned to me and whispered, “Thunder Woman!”

The Georgetown tournament was memorable for a couple of reasons. Stewart asked me to point out some of the more famous debaters. Our guys had on suits or at least sports jackets. One pair that Stewart was interested in was Ringer and Mooney, the guys from Catholic University whose affirmative case legalized marijuana. I said, “See that guy over there playing the air guitar and the tall skinny guy in the flannel shirt and the worn-out jeans. They are Ringer and Mooney.”

Bill Davey stopped in at the tournament to work the room laying on his inestimable charm. At the time he was clerking for Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart. He already knew Wayne and Mitch. I introduced him to Don and Stewart.

All the guys on the U-M team were much more comfortable debating affirmative. I told them about how successful Bill and I had been on the negative with the Emory switch. Wayne was not interested, but Mitch was rather eager to try it. As much as anything, I think that he just wanted to start his 1NC with “Flip your flows; here come the P.O.’s.”5

The most popular case that year called for the termination of nuclear power plants. Wayne found an article in which the author stated that leaving the uranium in the ground would cost thousands of lives because of the radiation from some element, radium I think. He thought that this evidence absolutely destroyed the “nukes” cases.

I was always skeptical about claims that appear in only one article. I pointed out to Wayne that the article did not specify over how many years these deaths would occur. It turned out that the half-life of radium was over sixteen hundred years!

Mitch and Wayne were at one point were experiencing difficulties with their Army Corps case when Mitch was asked in the first cross-x period, “How much is a human life worth?” No matter what Mitch responded, the negative had a clear path to a worrisome plan attack. I suggested that Mitch respond with a question:”Do you mean under the plan?” When they answered yes, he would then say that it would be “exactly the same as under the current system.” This seemed to work.

I could be wrong, but I think that only three of us went on the “Eastern swing” trip to Boston. I got angry at Mitch when he reported that he could not find a critical piece of evidence in a recently concluded round. I flung my legal pad across Harvard Yard in disgust.

My philosophy was, “If you can’t find it, you ain’t got it.” I did not think that anyone whom I coached spent enough time keeping his/her evidence orderly. One of my major frustrations in coaching was that I could never convince any debaters to implement my policy of numbering every divider section and putting that number on every card in that section.

I did a fair amount of research on prisons. I was convinced that a really strong case could be made for prison reform. Don and Stewart added it to their solar power case for a while, but they usually emphasized the solar case in rebuttals.

Debaters in those days wrote their names on the blackboard. Wayne and Mitch liked to goof around a little if they thought that the judge would appreciate it. They would sometimes call themselves “Mitch Egan” and “Wolva Reenes”. For Carl Flaningam of Butler they called themselves the Schidt Brothers, Sacco and Peesa.

As I mentioned, the top two debaters from Catholic University, Ringer and Mooney, ran an affirmative case that legalized marijuana. It was exceptionally difficult to attack. Their plan included a federal board to oversee the plan; they would sometimes even specify that the judge for the round would be a member of the board. However, all of the advantages came from legalizing cannabis, not regulating it. I suggested that we run a counterplan that was basically their plan without the board. We used it when we faced them, but we never defeated them.

I was conscientious about turning in my expense reports promptly after tournaments, but I don’t think that I earned any Brownie points with the department’s administration.

My most embarrassing moment in the seven years that I spent at U-M came during the high school debate tournament. It fell to me to announce the results at the final assembly. I made a serious error in scoring the speaker points, and, needless to say, no one checked my work. Some of the people to whom I awarded trophies did not deserve them. I had to purchase duplicate trophies for the real winners and send to all the schools that attended letters that acknowledged and apologized for the mistake.

Don Goldman and I went out for a drink after we found this out. It was the only time in my entire life that I really felt compelled to drown my sorrows.

At some point I noticed that the tournament brackets that Dr. Colburn had provided in an appendix to his book on debate were wrong. At first he denied it, but in the end he admitted that I was right. I guess that no one checked his work either.

For the district tournament Wayne and Mitch decided to use Don Huprich’s case on solar heating and cooling. I am not sure whether this was my idea or theirs, but I definitely supported it. Don helped them a lot to prepare.

Augustana and Northwestern again received first round bids to the National Debate Tournament, and again no other team from District 5 received one.

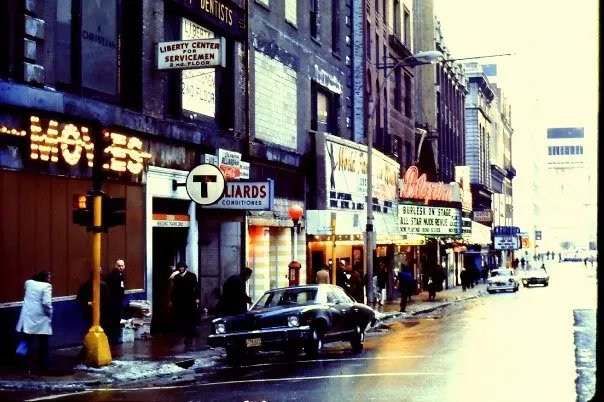

Wayne and Mitch went 6-2 at districts and qualified comfortably. So, we finally got to go to the NDT, which was sponsored by Boston College, but held at a hotel in downtown Boston.

I don’t remember who paid for the trip. We definitely took Greenie across Canada again. Wayne and Mitch finished in the middle of the pack.

I have only two strong memories. One was from the evening on which we accidentally wandered into Boston’s Combat Zone, which was only a few blocks from the hotel. This was a completely new experience for a Catholic lad from Kansas.

I also recall the evening that we spent exchanging evidence and ideas in the room of one of the debaters from, I think, Eastern Illinois. They had no idea what to say against Catholic’s marijuana case. We told them about our counterplan. They were intrigued enough to write it down. Mitch pontificated the opening sentence for them: “Once upon a time, when men were men and giants roamed the earth …”

Once again the only teams from District 5 that made it to the elimination rounds were the two pairs that received first-round bids, Northwestern and Augustana. The tournament was won by Robin Rowland7 and Frank Cross8 from KU, the two guys for whom I voted in the first elimination round that I ever judged at the tournament in Kentucky in 1974.

The drive back was long but by no means onerous.

Later we learned that the team’s budget had been cut drastically for 1975-76. For most purposes the program had been eliminated. Dr. Colburn’s title was still Director of Forensics, but the budget was not sufficient to attract anyone who was serious about debate. I still had a class or two to take, but I would not be the coach of that team. Don Goldman had finished his masters. I don’t know what he did next.

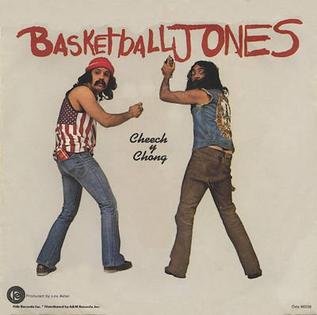

1. “Basketball Jones featuring Tyrone Shoelaces” was a popular song released in 1973 by Cheech and Chong. They somehow convinced an unbelievable assortment of people to help them. The song’s Wikipedia page is here.

Bob Jones contacted me in 2018 or 2019 about finding a bridge club in southeast Connecticut. He is a Diamond Life Master, a very high rank. In 2021 he lives in Marietta he lives in Marietta, GA.

2. Tom Rollins has had a fascinating career. You can read about some of it on his LinkedIn page. Among other things he founded The Teaching Company. I purchased several of its courses. I enjoyed listening to them on my Walkman while jogging.

3. In the twenty-first century laptops have replaced paper in nearly every area of debate, including note-taking.

4. In 2021 Melissa (Maxcy) Wade is the Executive Director Emeritus of the Barkley Forum at Emory University. To read about her career click on her picture on this webpage.

5. P.O. is short for plan objection. This includes disadvantages and arguments that the plan will not accomplish what the affirmative team claims.

6. Carl Flaningam practices law in Skokie, IL. His LinkedIn page is here.

7. Robin Rowland has taken to wearing bow ties at KU. His Wikipedia page is here.

8. Frank Cross died in 2019. His obituary is here.