The proverbial brass ring? Continue reading

Even before I became a professional software developer, my friends and acquaintances often approached me with their ideas for computer programs. It started in the Army with Doc Malloy’s idea for a tennis game, continued through graduate school, and was nearly ever-present in my business life. It seemed peculiar to me that so many people seemed to imagine that I had a skill that they lacked but no idea how best to employ it.

In point of fact, the limiting factor in software development was almost always money. A new software system required a substantial investment to cover development and testing costs, as well as marketing expenses. Very seldom did the people who propose these project give any thought to helping to finance them. At least they never volunteered information about having a secret source of funds. They evidently thought that they should share in the imaginary profits because they provided the original idea. I sometimes told them, “ideas are a dime a dozen. Implementation is everything, and marketing brings it home.”

I had plenty of ideas of my own. A few of them, such as the idea of running several simultaneous “threads” for the cost accounting programs generated a bit of revenue for TSI. One of my ideas, the use of a butterfly-shaped website for insertion orders and emails for notifications, resulted in a very profitable product for TSI, AxN. The genesis of its design and the marketing concept that turned it into a financial winner is described here.

TSI’s clients also had a large number of ideas for programming, but they seldom expected us to work pro bono. I spent many hours researching and writing quotes for changes to our systems requested by our clients. I doubt that a month went by in which I failed to produce produce ten or twenty of them. I considered my most important responsibility at TSI to be providing a clear description of each requested project and assigning an appropriate cost figure.

Very seldom did someone approach me with a project that included funding. I can think of three times in forty years. Only one of these concerned software that we had already designed and coded. The person making the proposal was Gilbert Lorenzo1, who was one of the top bosses in the advertising department at Burdines, the Florida division of Federated Department Stores.

Gilbert telephoned TSI’s office in the early nineties. He had received one of our first mailings about AdDept, our administrative system for large retail advertising departments. He said that he would be in New England to meet with some people at Camex2, the company based in Boston that marketed a system for digitally producing page layouts for newspapers and large advertisers. He requested us to show him a demonstration of the AdDept system.

We reserved some time in a demonstration room at the elegant IBM office in Waltham, MA. We had a relationship with this office, but we had never done an AdDept demo there before. I arrived there as early as I could to get the system set up for my presentation. It was a very nice facility that always impressed potential clients.

The AdDept system in those days was fundamentally sound, but many “bells and whistles” were added on in the subsequent decade. In almost every case they were suggested by and paid for by one AdDept client or another.

The most impressive thing about the demos in the early years was the speed with which the programs moved from one screen to the next. Once the tables were set up, a user could define all aspects of a new ad to run in dozens of papers in just a minute or so. This always generated the biggest “Wow!”

In our discussion after the meeting Gilbert said that he liked what he saw. He might have even said that he wanted to buy the system. However, I did not hear from him again for several years. This was consistent with what always seemed to happen with Federated’s divisions, a phenomenon that is explored in more detail here.

Meanwhile Burdines was—unbeknownst to me—experiencing explosive growth. In 1991 alone the number of stores increased from twenty-seven to fifty-eight through the assimilation of two Federated divisions— the Maas Brothers and Jordan Marsh stores in Florida. More stores were added throughout the rest of the nineties. By the end of the decade Burdines dominated the department store market throughout the entire state.

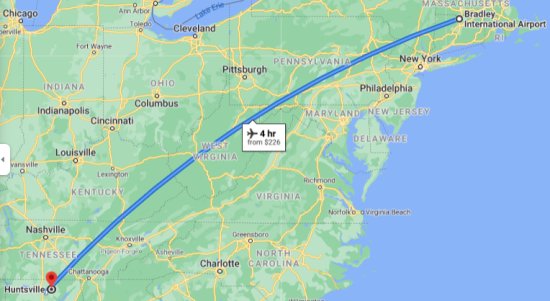

The purpose of Gilbert’s second contact with TSI was to invite me to Huntsville, AL, the home of a software company with which he was working at the time. I don’t remember the name of the company. I do recall that two of the team assigned to this project formerly worked as software developers at Camex before DuPont purchased the company and changed its focus. One of them was Mike Rafferty3, whom I had met at Camex’s headquarters when our common customers had requested that an interface should be constructed between the two systems, a project that was described here.

The software company in Huntsville had a very impressive headquarters. As I understood it, the company’s primary customers were NASA and companies that worked with NASA. That was de rigueur in Huntsville.

Gilbert explained that he was working with Mike and the others to develop a comprehensive software system for the advertising department at Burdines, and he hoped and expected that the other Federated divisions would also use it. He wanted TSI (or at least me) to participate in the project, and he insisted that he had the funding for it.

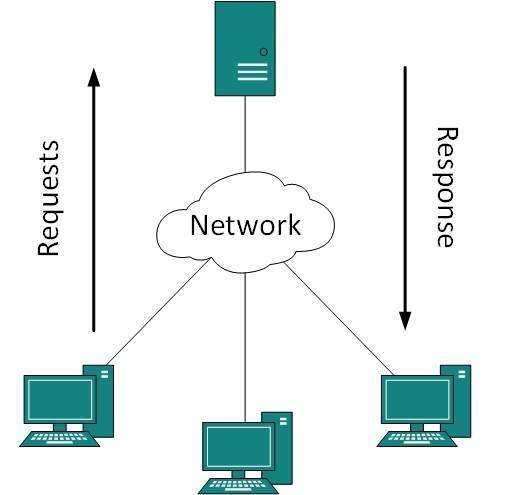

Mike described their approach to the project. They intended to use a home-grown database that resided on a server, but most of the programs would reside on the individual “clients”—PC’s or Macs. When I told him that TSI’s programs were written in BASIC, he suggested that we consider converting them to use Microsoft’s Visual Basic.

Most of the discussion concerned the scope of the project. They were interested in integrating something like AdDept into the unitary structure that they envisioned. No one addressed how TSI would be integrated into the development process. Maybe they expected me to fill in some of the details or to volunteer to research how difficult it would be. Maybe they knew that we seldom backed down from a project just because it was difficult.

The atmosphere was cordial and positive. I remember that we all went out to lunch together, and I ordered a Monte Cristo sandwich. Nevertheless, this meeting made me very uncomfortable. On the one hand, the prospect of installing a version of the AdDept system into all the remaining Federated divisions was way beyond tantalizing. It would be a dream come true. What they suggested would undoubtedly a big job, but TSI had a talented group of programmers who were quite familiar with both the subject matter, and the way that I liked to approach big challenges.

On the other hand, from my perspective the way that this project was described was adorned with “red flags”.

- I had already researched the possibility of using Visual Basic. It might have been possible to convert some of the programs, but there were no tools designed to help. It would certainly have taken TSI several years to produce a workable system. We would be discarding all of the tools that we used in favor or ones that we had never used and, to my knowledge, had never been used by anyone in a data-intensive situation. TSI’s programmers would certainly need a lot of training. We would probably need to hire skilled employees or at least consultants to achieve any degree of efficiency.

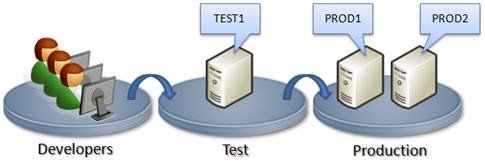

- Their whole architecture was different from what we used. In the AdDept system the data and all the programs resided on the AS/400 server. The “client-server” approach that they proposed located the data on a server, but the program were all distributed to the PC and Mac clients. To me this sounded like an administrative nightmare. All changes—including emergency fixes—must be installed on all of the clients.

- I considered the AS/400 integral to AdDept’s success, and so did our customers. The operating system code was built on the database rather than the other way around. That meant that the system itself could never be used for programs with the the huge requirements for memory, disk, and processing speed that design and creation of advertising layouts required. The AS/400 was definitely not designed for that. However, it was ideal for administrative systems like AdDept. It competently handled so many problems with which all-purpose operating systems constantly struggled.

- I trusted IBM and the AS/400’s database. I knew how to get the latter to function efficiently, and IBM’s support was unmatched in the industry. The idea of converting to a home-grown database seemed just preposterous.

- By the time of the meeting in Huntsville TSI had finally turned the corner. The AdDept product had a solid client base and a good number of prospects outside of Federated. How could we continue to pursue AdDept development for those companies—which was relatively certain to generate revenue and good will—while devoting a great deal of time and attention to the massive Federated project? It did not seem possible to me.

- Gilbert had said that he had funding, but he never provided any details about who, how, or how much.

Something about the project sounded fishy to me. They were interested in my participation, but they never specified how. Did they want to buy TSI? No one mentioned anything like that. Did they want to hire some or all of us? Did they just want me to consult with them as to the system design? Or was there something else?

At the end of the meeting, Mike asked me what format TSI preferred for exchange of information. Both of the programmers were very surprised when I told them that our offices were connected to all of the clients’ AS/400s via phone lines. We used the AS/400’s built-in messaging and word processing. No one had ever asked us to communicate outside of that.4 I told them that TSI’s employees had PC’s, and the company had a few modems, but we mostly used the PC’s as terminals to the AS/400.

The group did not come to any agreement about how the project was to proceed. I had an impression that they thought that I (who was well into my fifth decade on the planet) was a fossil. I, on the other hand, thought that they, who had dealt almost exclusively with production of ads for newspapers, dramatically underestimated the difficulty of designing a single multi-user database that was capable of handling all aspects of scheduling and managing the financial aspects of all media. The planning and cost accounting modules were even more challenging.

After the meeting I had a little bit of private time with one of the principals of the software company. He asked me what I thought about the project. I told him that it was interesting, but I did not see the ROI (return on investment) for combining the two systems. I remember his exact words. “ROI. Oh, yeah, where’s the ROI?”

I did not hear from any of them again, and I did not press for inclusion in their project. In all honesty I had too many other things demanding my attention. After a year or two I sometimes wondered whether Gilbert had abandoned the project or had gone ahead with it. The answer, it turned out, was somewhere in between. I spent no time searching for information about the project, but little hints turned up occasionally.

Our liaison at Lord & Taylor, Tom Caputo, described to me his experience interviewing for a job in the advertising department at Bloomingdale’s, a Federated division in New York City. He asked the people there about their computer system. They showed him boxes that contained the software for the FedAd system, which Federated had sent them and told them to use. The people at Bloomies had never unsealed the boxes.

When I installed the AdDept system at Macy’s South5 in December of 2005, TSI’s liaison there was Amy Diehl. Her official title was “FedAd Coordinator.” By then I knew that FedAd was the culmination of the project begun by Gilbert Lorenzo more than a decade earlier.

I soon learned that the advertising department at Macy’s South was not actually using the FedAd system at all because the programmers had admitted that it could not handle the department’s planning process. Instead they had been using parts of a previous version called Assets for a few tasks. I was astounded to learn that the Assets system used a Microsoft Access database. They had sent a boy to do a man’s job! Federated Systems Group no longer supported it.

Later we heard that Macy’s East was using the FedAd system, which by then had been given a different name. At the time its advertising department was still using the Loan Room system that TSI had written and implemented for them in the early nineties. That meant that for years the details of every ad were being entered into at least two separate systems.

I even quoted a bizarre request from Macy’s systems people to write an interface between their system and AxN. I provided them with a quote, but nothing came of it.

In all of that time—more than two decades—I never heard anyone say anything good about FedAd. As far as I know it generated a great deal of expense and not a penny of revenue for the company. I only knew of one department that used it. TSI, in contrast, sold and installed thirty-five AdDept systems, each of which was customized to the needs of the individual departments.

On the other hand, I might have been able to carve out a career as the guru for Macy’s concerning administrative software for advertising. That would have certainly been something to crow about. After all, when the game was finally ended, Macy’s had all the marbles.

I doubt that they would have let me—and whatever portion of TSI was involved—participate from Enfield or East Windsor, and I doubt that they would have let us continue to perform or oversee work for their competitors. They might have allowed me to program for the AS/400—I saw several of them at the FSG data center in the Atlanta area. However, it was more likely the Gilbert would have required everyone in the process to use the same database. He seemed to be calling all the shots.

So, I probably would have had to sell my soul to Macy’s. I might have made a lot of money, but I think that I would have been miserable. Almost everyone in my acquaintance who had worked for one of our clients and then worked for Macy’s or a Federated division quit in the first few years and was openly bitter about the experience.

Finally, I must add that I suspect that there was a good possibility that the invitation to Huntsville was just a ruse to get me to expose the totality of the AdDept system to people who might be able to replicate it.

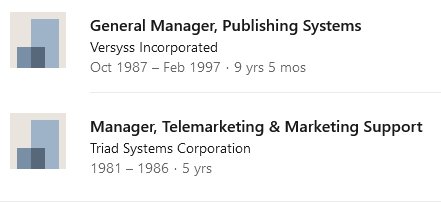

Epilogue: While researching the blog entry for TSI’s relationship with Federated Department Stores (posted here), I discovered that Val Walser’s LinkedIn page prominently features how she “directed development of a sophisticated, integrated software product” in the division run from Seattle. It must be referring to the system that Gilbert and Mike envisioned so many years earlier. I never heard anyone mention any other such system.

1. For some reason Gilbert Lorenzo has two LinkedIn pages. They are available here and here.

2. The Camex system was used by both of the first two AdDept users, Macy’s East, and the P.A. Bergner Co.

3. Mike Rafferty’s LinkedIn page is here. It did not provide much information about him when I discovered it in 2022.

4. Keep in mind that the Internet was in its infancy. At that time Microsoft had not yet completed its domination of the word processing and spreadsheet markets. Technical people used “message boards”, not email, for communication. AOL did not hit the web until 1997.

5. The installation at Macy’s South is described in detail here.