Classes in the middle years. Continue reading

To the best of my recollection this was my undergraduate academic schedule at Michigan:

| Freshman | Fall 1966 | Math 195 | Russian 101 | Chem 103 | Latin 350 |

| Spring 1967 | Math 196 | Russian 102 | Chem 106 | Greek 101 | |

| Sophomore | Fall 1967 | Math 295 | Comp Prog | Econ 101 | Greek 102 |

| Spring 1968 | Math 296 | Comm Sci | Sp Persuasion | Greek 201 | |

| Junior | Fall 1968 | Math 395 | Econ Intl | Sp Debate | Greek 202 |

| Spring 1969 | Math 396 | Topology | Homer | Thucydides | |

| Senior | Fall 1969 | Probability | Statistics | Psychology | Euripides |

| Spring 1970 | Sp Study | Linguistics | Russ Lit | Anthropology |

The classes for the first semester of freshman year (fall 1966) are discussed here.

The classes for the second semester of freshman year (spring 1967) are discussed here.

The classes for the second semester of senior year (spring 1970) are discussed here.

Here is what I remember from the middle years by subject:

Math: The three-year basic sequence (195-6, 295-6, 395-6) started with a review of calculus. The last semester covered, I think, the calculus of several—more than three—variables. It was during this last class that I realized that I had absolutely no interest in being a mathematician. I could no longer visualize what was being talked about. I am sure that it is valuable for things like string theory, but it was not for me.

In fact, I was lucky to last that long. These six classes were all taught by professors, as opposed to graduate students.1 We were expected (but not required) to do the problems at the end of each chapter of the text. I looked at them, but I never did them. Our tests asked for proofs rather than solutions to problems. The material became more and more difficult as the course numbers got higher. I familiarized myself with the concepts, but I did not actually learn them. That was not my goal; my goal was to pass the tests.

I developed several techniques for pretending to prove that formula A is equivalent to formula B, which is the format for most, but not all, mathematical proofs. It would be best to come up with an actual proof, but this is not like horseshoes or hand grenades. Coming close can count for a lot. I thrived on partial credit.

The first technique is known as proof by induction, a legitimate and powerful method absolutely essential for proving some mathematical concepts. It even has its own Wikipedia page. Any time than something countable—an integer or even a rational number—was mentioned in either formula A or formula B, I would used proof by induction. It was always good for a half-page of paper, and I never got less that seven out of ten points. Occasionally, it actually produced the required proof.

The technique that I invented and perfected was the Wavada Squeeze. You will not find it on Wikipedia yet. Here is how you do it: Start with formula A, and in a column beneath it make as many manipulations of it as you can think of. For example, you could multiply and divide by something: A=((x+3) x A)/(x+3). After ten or so manipulations, you end up with something quite different from what you started with. On a separate sheet of paper perform a different set of manipulations on formula B. Once in a while one of the two will actually show the way to a proof, and that’s great. However, even if neither does, you can maximize your partial credit by writing the the manipulations of B in reverse order beneath the manipulations of A. This will give you a “proof” that A=B with twenty or so legitimate manipulations, and one horrible leap somewhere in the middle. This was usually good for at least five out of ten, which was much better than nothing.

I made the mistake of taking one graduate-level class, Topology. I ended up with a C, which is a terrible grade in a graduate class. I remember entering the classroom on one Monday after a debate tournament. Everyone was busy writing their names on “Blue Books”, which meant that an exam was about to take place. This was news to me. Evidently, it was announced in a class that I had not attended. Usually I tried to make sure that I had a friend in classes to warn me about such events. This class, however, was composed of graduate students in math. None seemed approachable. I got one right out of nine. Showing up clueless in a classroom full of people with Blue Books appeared frequently in nightmares over the decades.

I am embarrassed to say that not only have I forgotten the names of these teachers, but I also have only vague recollections of any of the concepts, never mind the details, of what I supposedly learned. I never considered graduate school in math.

Actuarial Science: I passed part 1 of the actuarial exams in May of 1969. I took two classes from Cecil Nesbitt2, a very famous actuary, in the fall semester of 1969 with the half-hearted purpose of passing part 2—probability and statistics. I was not a bit impressed with the quality of the other students, when compared with the guys (and girl) in my math sequence.

My attendance in both classes was extremely spotty. I did not do any of the assigned problems. Nevertheless, I thought that I had passed part 2 in November, but i was wrong. The exam was offered again in May, but I was not upset enough about this failure to study more in the spring session. The result is described here.

Cecil Nesbitt’s Wikipedia page is here.

Greek: For the first two Greek3 classes the teacher was H.D. Cameron.4 I can clearly visualize the professor who taught the 200-level classes as well, but I am embarrassed to report that I cannot remember his name. He also taught the Thucydides class.

My clearest recollection of those last two classes in the sequence involved the final exam. With less than one hour remaining before the Greek final, I realized that I had misread the exam schedule and studied for a different subject. The exam for that subject was a day of two later. So, I ended up taking the Greek test with practically no cramming.

Thank goodness it a Greek course was the one to which I gave insufficient attention; I got an A anyway. If I had neglected the other subject (I forget what it was), I would have been in a world of hurt. This kind of thing was also a subject of many future nightmares.

In all honesty the university should not have allowed me to take these four classes. My high school Greek class was good enough that I could almost certainly have placed out of Greek. However, there was no placement test for Greek at U-M. I am thankful for the lack; I received four easy A’s.

The Homer and Thucydides classes were more difficult. All of the other students in both classes were graduate students who took nothing but Greek classes and spent all of their daylight hours in the classics department. I was lucky to survive.

I enrolled in a course that translated the plays of Euripides. I had to get special permission from the professor to join. However, after a week or two I dropped the class. It was just too demanding for my schedule.

If I had applied to graduate school in 1970, I would have tried for a masters in the classics. These were the only classes that I enjoyed the most.

Speech: I took only one real speech class, persuasion. It was taught by Bruce Gronbeck.5 The other two speech classes were gift A’s to compensate for the time that my participation in debate consumed.

I went to the persuasion class every time that I was in town. I gave all the speeches and turned in the assigned paper. I found the material presented boring, but the speeches were quite interesting.

I have several vivid recollections. We talked about some of the speeches as a class. In one situation I remarked that I thought that the speaker had seemed sincere. Prof. Gronbeck asked me why I thought that, and I was stumped. Nobody else really had a better answer. As Jean Giraudoux famously noted, “The secret of success is sincerity. Once you fake that you’ve got it made.”

Jim Pitts, the captain of the basketball team, was on the roster for the class, but he never attended, not even for the assigned speeches. Prof. Gronbeck told Dr. Colburn about this, and a few days later Jim appeared, and he was prepared to give a speech. No speeches were scheduled for that day, but he was allowed to deliver his speech, which was about abortion.

Jim took the floor with about twenty 3″x5″ cards held in very large hands. The use of a deck of cards in a speech is always a bad idea unless you plan to demonstrate how to throw them. Jim’s first line was “The chances of getting an abortion in this country are 1. Slim and 2. None.” On the fourth card he could not read the handwriting of whoever wrote the speech. A few cards later the cards were in the wrong order, which always seems to happen. When he finished the speech, Prof. Gronbeck thanked him, and no one else said anything. The class then continued as usual.

That was Jim’s last speech, but he never missed any basketball games that year.

Prof. Gronbeck wanted to hold a one-on-one debate, and I volunteered. My opponent, who was from Germany, chose as the topic the reunification of her country. She was against it. It wasn’t much of a debate. I had to go first, and we only got one speech each. She made no attempt to refute anything that I had said.

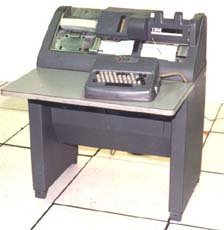

Communication Science: For some reason in those days the academic department at U-M that dealt with computers was called “Communication Science”. I took two courses. The first was the introductory programming class. My instructor was Господин Muchnik, whom I already knew as a student in my first-semester Russian class. We learned to program in MAD, which stood for Michigan Algorithm Decoder, a programming language used nowhere else in the world.

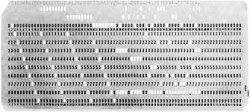

There were no terminals. We had to record our programs and our data on eighty-column IBM cards. This required use of a machine to punch the cards. Each card corresponded to a line of code or a row of data. There was no backspace or delete key. If you made a mistake when you punched the, you had to eject the card and throw it away. The university had a dozen or more of these machines for students, and they were located on the other side of campus. If they were all in use, you just had to wait or come back later.

When you finally had your program and data punched, you inserted the deck of cards into the pre-compiler, a small machine that found syntax errors in MAD programs. When you fixed all of the errors that it found, you were ready put a rubber band around your deck of cards to submit a job to the computer. The operator would accept the job, assign it a number, and give you a card with your job’s number and a phone number for a recording that announced the number of the job that the computer was currently on. It might be hours or even days befor the announced number was greater than the number of your job. When it finally happened, you walked back to the computing center to retrieve your output and your deck.

The first few times that you did this, the output consisted of a list of errors. If there were only a few errors, you would wait for a keypunch machine to be available, fix the errors, and resubmit the deck. This process went on until you either despaired or were euphoric when you finally got some results.

For our final project we could do any program that we wanted. The only requirement was that it be at least one hundred lines of code. My project read in a bridge hand of thirteen cards and output the opening bid using the standard American system taught by Charles Goren. I did it over the Thanksgiving holiday when there were no lines for the keypunch machines, and shorter waits for the jobs. I got it to work well pretty quickly.

Needless to say, I really liked programming, and I was good at it.

The other Comm Sci class that I took was a strange amalgam of language theory and the history of computer languages back to the Turing machine. I did not get a lot out of it.

Economics: You cannot debate as much as I did without doing quite a bit of research into economics. By the time (sophomore year) that I enrolled for the introductory class at U-M I had already read hundreds of articles and several books on economics. The format for the class was lecture plus recitations. I enjoyed the lectures, although my memory of who gave them cannot be correct. I found the recitations tiresome and overly simplistic.

I studied for the final with my debate partner, Gary Black, a senior. I helped him more than he helped me. I was more than a little peeved when he got a low A, and I got a high B.

I took one more economics class. I did not like anything about the way the course in international economics was taught. I put in as little effort as possible. I think that I got a C.

My enduring impression about the field of economics was that it was 99 percent unproven theories. I was right. The next fifty years proved conclusively that most of what I was taught was just wrong. In fact, Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist, won a Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for demonstrating that the basic behavioral assumption underlying all economic analysis is nonsense.

Psychology: As a senior I signed up for the introduction to psychology in the honors program. I was allowed to take one class pass-fail, and this was the one that I selected. Grades lower than C were unheard of in honors classes. So, I correctly determined that I could pass this class with virtually no effort.

The teacher was a female graduate student, and she insisted that we understand the principles of feminism. Most of us had never heard of the word. I remember very little else about the class, except that it was full of freshmen with first names like Hill or Twink. Twink told us that in the home in which he grew up no one ever questioned Freud’s teachings. I found that astounding, but I suppose that it is no more astounding than believing in the Book of Mormon or, for that matter, the Bible.

Twink was a fairly big guy, maybe 6’3″. Once I was walking somewhere with my friend, Tom Rigles, who had already heard me tell stories about him. Tom said that he did not imagine him being so big. I casually remarked that I could take him. Rigles scoffed at me. As God is my witness, I could take Twink then, and if he is still alive, I could take him now.

I don’t think that the psych class had a final exam, but we were required to write a paper. I had picked up a book called Games People Play by Eric Berne. The night before the papers were due, I skimmed the book and wrote and typed the paper. It was the third and last paper of my entire undergraduate career

I disliked all the “social science” courses that I took. If you had predicted in 1970 that I would voluntarily take almost nothing but social science courses for six years in graduate school, I would have told you that you did not know what you were talking about.

1. Ted Kaczynski, the notorious Unabomber, was a graduate assistant in the math department at U-M during the sixties. The offer of the teaching position was the main reason that Ted chose Michigan over Cal Berkeley and the University of Chicago.

2. My best friend since 1972, Tom Corcoran, worked as an actuary. One year I was shopping for a birthday card for him. I looked through about twenty humorous cards until I found one that actually mentioned Cecil Nesbitt! I was absolutely astounded.

3. I learned classical Greek in high school and college. Decades later I tried to teach myself modern Greek in preparation for a Hellenic vacation. The alphabet was the same, and the grammar was similar. However, the vocabulary and pronunciation were drastically different.

4. Professor Cameron in 2020 is emeritus in the classics department and curator of the university’s Museum of Zoology.

5. Professor Gronbeck died in 2014. A very lengthy obituary can be read here.