Debate in the middle years. Continue reading

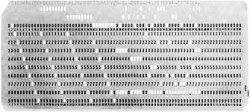

A primer explaining the format and other details of intercollegiate debate can be found here.

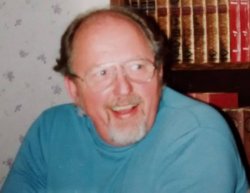

Fall 1967: When I returned to school after the summer of 1967, I discovered some very important changes in the debate program at U-M. Dr. Colburn was still the Director of Forensics, and Jeff Sampson was still coaching. Juddi (pronounced “Judy”) Tappan, a high school coach from Belleville, had been added to the staff. My recollection is that in her last year at Belleville two girls from her team had won the state championship.

Juddi’s assignment at U-M that year was to coach the novices. She had a very good crop. I think that both of those girls from Belleville came to U-M. One might have participated in debate for a short while, but by the time that the tournament season started, neither was involved. The four principal players were Bill Davey, an exceptionally smart guy1 from Albion, MI, Ann Stueve from Kentucky, Jim Fellows, whom I never got to know very well, and Alexa Canady from Lansing. All four of them were almost certainly better debaters than I was when I first set foot in the Frieze Building a year earlier. They all definitely had more experience than I did.

I think that there was one other coach, but he spent little time with any debaters and none with me.

For me the debate season began bizarrely. Jeff Sampson escorted me and either Bob Hirshon or Lee Hess to Expo ’67 in Montreal to debate against two guys from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh about abortion. The whole debate only lasted for a little over thirty minutes and was attended by the coach/escorts of both teams and three ladies who had years earlier passed the age for which family planning is much of an issue. The guys from Duquesne had done quite a bit of research and presented a lot of serious arguments. We mostly told jokes.

Surely this was an appropriate metaphor for the age: four young guys debating about the circumstances in which women should be allowed to have abortions. Moreover, two of us were not even taking it seriously.

I don’t remember that we took an airplane to Montreal, but neither do I recall a long car trip with a border crossing. I retain a rather vivid memory of a rude cab driver who pretended that he did not understand English. If we had a car, why would we take a cab? Maybe parking was an issue.

This trip was undeniably a waste of time and money; perhaps some other organization paid for it. The plus side was that we did have time to wander around the Expo for a day or so. My strongest memory of the fair itself is eating a reindeer sandwich at one of the Scandinavian pavilions. It tasted a little funny, but it was not awful.

I also remember that we attended a performance of Laterna Magika, a multi-media theater troop from Prague, which at the time was on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Jeff chided me for trying to figure out what message was being conveyed.

Years later my wife Sue told me that she was also in Montreal during that period, had heard about the debate in which we participated, and almost went to it. This was five years before I even met her. So, this was almost a great story.

I considered the national debate resolution for that year, “that the federal government should guarantee a minimum annual cash income to all citizens”, uninspired. I cannot remember much about the individual arguments. Of course, debaters argued whether the states were “closer to the people” or whether in-kind payments were better than cash, but I cannot imagine that there would be enough meat there for a year’s worth of debates.

I think that I had three partners during the year:

- I remember debating with Larry Rogers, a junior, at the tournament at the University of Illinois Chicago Circle (UICC). I remember that he performed brilliantly in one debate, but overall we did not do well together, and I did not enjoy the experience at all. I also remember that one morning he took what he called “a Polish shower” with Right Guard before he dressed for the debates that day. By the way, all the male debaters wore suits Larry quit the team before the end of the year.

- I am sure that I debated in at least one tournament with Lee Hess, another junior, who was my partner during the whirlwind spring 1967 season. I have a vague recollection that we debated together at Ohio State, but details have escaped from my memory. Lee had a motorcycle. I think that he might have had an accident with it that semester.

- My third partner was Gary Black, a senior. I think that we did well together at one tournament, but I don’t remember the details. The main thing that sticks out in my mind is that I did “outsides” on the affirmative, which meant that I delivered the first affirmative constructive and the second affirmative rebuttal. Usually, this is only done when one debater is much better than the other, but my speaker ratings were generally equal to or better than Gary’s. He designed the affirmative case; I could not have defended it with much enthusiasm.

I might have debated with Bob Hirshon at one unmemorable tournament.

Spring 1988: Just before finals for the fall semester Jeff took me, Lee, and Gary aside, and had us write down on a sheet of paper the name of the other member of the trio that we would prefer to debate with. They both chose me. Although I chose Lee, Jeff decided to pair me with Gary for the important tournaments in the second semester (January-March 1968).

Here is what I remember of that time.

- Both Lee and Bob quit debating before the semester began.

- Gary and I had a practice debate against Bill and Ann in which we performed badly. Juddi remarked that it was a classic case of the novices showing up the varsity. I was too arrogant to get upset by this.

- Gary and I made the elimination rounds at a few tournaments, but we did not have any exceptionally good performances.

- We went 2-6 at Northwestern, which was an improvement over what I had done as a freshman.

- Gary and I flew unaccompanied to a tournament at Loyola of Baltimore. The field was weak. I think that we qualified for the elim rounds, but then we lost. I lost my overcoat on this trip. Another passenger evidently took mine from the overhead rack by mistake when the plane stopped in Pittsburgh.

- Throughout the year ballots from several judges remarked that I should tone it down. I would start out at a reasonable volume, but after a while I got excited and started shouting. I worked on this.

- Jeff did not work with Gary and me as much as he had helped Lee and me the previous year.

- At the District 5 qualifying tournament for the NDT Gary and I were 4-4 with twelve ballots out of twenty-four, exactly average and exactly the same as Lee and I did the previous year.

- Both freshman teams did quite well throughout the year. I don’t remember the details.

Jim Fellows decided that he did not want to debate any more.

The summer of 1968 was definitely unique. Assassinations led to destructive and bloody riots. The suburbs of KC, where I was, were not affected, but Detroit, one of the centers of the protest, is less than an hour from Ann Arbor. The police also rioted outside of the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago. Then Nixon disclosed the existence of his secret plan to end the War in Vietnam.

I had my first real job in the actuarial department of the insurance company that my dad worked for. My summer adventures are described here.

Fall 1968: Jeff Sampson moved on. Juddi made all the decisions about partnerships. She also did whatever coaching was done.

The team had one very talented freshman, Mike Hartmann. He had a pretty good partner, Dean Mellor.

The resolution was “that executive control of United States foreign policy should be significantly curtailed.”

I was paired with Alexa. We ran a case that banned deployment of troops to fight without a congressional declaration of war. I was first negative and second affirmative. Bill and Ann were the other varsity team.

Here is what I remember of the first semester.

- I enjoyed debating with Alexa. I had never had a female partner before. She was a talented debater and a good partner, but the thing that really impressed me was that she carried her own evidence boxes.

- A small percentage of varsity debaters were female. Black debaters were very rare. Alexa was the only Black female debater whom I ever saw at a varsity tournament in my four years as an undergraduate debater. This could not have been easy for her.

- In one round we faced a good team that presented a a plan to use American food to feed starving people around the world. I had heard of this and done a little research, but I had never discussed it with Alexa. I decided to argue topicality and to present a counterplan that included all aspects of the affirmative plan, but no reduction in executive control. Alexa did not know what to argue in the second negative, but she soldiered on and did not complain, even when we ended up losing the round.

- Our best tournament was Ohio State. We made it to the semifinals, which qualified us for the Tournament of Champions. We might have been the first U-M team ever to accomplish this.

- For some reason Juddi drove us to Oshkosh, WI, to a second-rate six-round tournament at the state university there. In the first round we debated a really obnoxious team from Ripon College on our affirmative. The second round was allegedly power-matched, but we were scheduled to meet the same team on the same side! I immediately complained to the staff. I was told that we should just switch sides. I really did not want to debate that team again, but we had no choice. The teams that we faced after that were a little better, but I was depressed after the last round. Then they announced the results. I was astounded when they announced that Alexa was the second-place speaker. I never had lower points than she did, and, sure enough, I won the award for top speaker, which, as I recall was a hearty handclasp. Alexa and I had won all six debates and qualified for the quarterfinals, where we were quickly eliminated on a 2-1 decision that no one in the audience could believe.

- Juddi smoked. She expected one of the males to light her cigarettes for her.

- We stopped for gas once when Juddi was driving her own car. She purchased $.50 worth of regular.

- Juddi wore a LOT of makeup. Alexa, who roomed with her on trips, said that it was frightening to see her when she first got out of bed. One of the other grad students said that Juddi always looked like a million dollars, but you had to suspect that at least half of it was counterfeit.

- Before final exams both Ann and Alexa quit the team. So, Bill and I were the only varsity debaters left.

Spring 1969: The first tournaments that Bill and I attended together were at Harvard and Dartmouth in January. Juddi made the arrangements. We drove to Oberlin College in Ohio to pick up their team, Roger Conner2 and Mark Arnold, and their coach, Dan Rohrer. We then proceeded to Buffalo to pick up a team from Canisius College. I never heard of teams car-pooling to debate tournaments, and this was uncomfortable, at least for me. Mark Arnold disliked me intensely. Also, the Oberlin and Canisius teams had much better records than we did.

We definitely attended the tournament at Northwestern. I think that we were 4-4, which continued my trend of improvement over the previous year with three different partners.

The only other tournament that semester that I clearly recall was the very long drive to Minneapolis to attend a tournament at St. Thomas College, now known as St. Thomas University. I think that this was the first time that Jimmie Trent, a famous debate coach and a professor in the speech department at Wayne State, accompanied us. We attended a peculiar set of tournaments for the next year and a half. It was not until considerably later that I began to suspect that Juddi tried to schedule tournaments that she was reasonably certain that she and Jimmie would not run into anyone from Wayne State.

Jimmie definitely was very knowledgeable about debate, and he was also great fun to be with on tournaments. He specialized in my favorite kind of humor, the shaggy dog story, which was ideal for a long drive. His presence almost counterbalanced having to deal with Juddi. At some point they got married, but, as far as I could tell, that did not change the political implications of a Wayne State speech professor helping U-M debaters.

The tournament at St. Tom’s was at best second-rate. It did not even supply standard ballots for the judges. They had to fill in these yellow cards that rated speakers on a twenty-point scale instead of the thirty point version. There was also very little space for the judge to express the reasoning, if any, behind the decision.

The three feet of snow on the ground made traipsing between buildings carrying our evidence a real pain and led everyone to question the motivation for the trip.

Bill and I went 7-1 in the prelims. That made us the top seed in the elimination rounds, which, as I recall, began with quarterfinals. Almost all tournaments used seeded brackets for the elimination rounds, but not this one. Instead, for some reason, they drew the pairings at random. In the quarterfinals we ended up debating against a team from Augustana College in Illinois that we had already defeated on our negative. We were “locked in” on the affirmative because tournaments generally guarantee that no team will debate another team twice on the same side.

This was the worst possible draw for us. I had a much better record on the negative throughout my career, especially with Bill. It was a tough round. I will always think that I won this round with a joke. I started my last affirmative rebuttal with this remark: “I have been wondering why Mr. ______ (the second negative) wore galoshes to the debate. Now that I see all the snow that they tried to bury the plan under, I understand. Let’s start digging.”

Everybody in the audience laughed. We won the room and two of the three judges.

In the semifinals we faced the team that gave us our only loss in the prelims. However, this time we were locked in on the negative and won easily.

In the finals we faced two guys from Iowa whom I had debated several times over the years. We were locked in on the affirmative. As it turned out, in the elimination rounds we faced the second, third, and fourth seeds, in that order. All were teams that we had already debated.

At this point in the year we had a pretty strong non-intervention case, but we also had a food case that we had pulled out (successfully) a few times that year. The northern plains was a very conservative part of the debate world, and so we decided to stick with the non-intervention case.

Just before the debate started, they introduced the five judges. Two were debate coaches with whom both teams knew pretty well. Three of them were local luminaries. Of course, we did not get to interview them, and so we had no way of know how familiar they were with debates at this level.

Debate coaches have a lot of practice at following arguments. The best tactics for dealing with inexperienced judges are not at all as clear as they are for dealing with debate coaches. The thought occurred to me that we should perhaps run the food case. Any yokel can relate to starving millions. However, it was only a flickering thought; we went with our original plan.

We won both debate coaches, but lost the three civilians. I will always think that if we had used the food case, we would have won the outsiders and maybe lost the coaches. I had plenty of time to think about this on the long drive home. Winning this (or any) tournament would have been a feather in our cap. Finishing second in such a sorry gathering made us just an “also ran”.

Bill and I went 4-4 at the district qualifier in March. We only won eleven ballots. So, I appeared to be regressing a little.

During the summer I worked in a the actuarial department of Kansas City Life, not my dad’s employer. Two other guys, Todd and Tom worked there. One day someone asked if they had gone to lunch, and I was able to use a line I had been saving for weeks: “Tom and Todd wait for no man.”

Man also landed on the moon.

Fall 1969: I learned that two strong additions had been made to the debate staff, Roger Conner1, who had an exemplary record debating at Oberlin, and Cheryn Heinen, a very good debater from another strong debate school, Butler. Roger and Cheryn could probably have been a big help, but they were seldom allowed to go to big tournaments, and neither planned a career as a debate coach. Because the program had very few debaters, we hardly ever had practice rounds, and when we did, Juddi ran them.

Since Bill and I were the only debaters on the team with experience at the varsity level, I had assumed that we would be paired up from day 1. Partner-switching is uncommon at most schools.

I was therefore unpleasantly surprised and disgruntled to find myself paired with Dean Mellor at the beginning of the year. Bill and Mike must have also been debating together.

Cheryn did not work with us much. Still, the most memorable event of the semester occurred when she was driving us in a car from the university’s motor pool westbound on I-94. There were three other debaters in the car. One was certainly Bill. The other two must have been Dean and Mike.

The car was proceeding at the speed limit when all of a sudden the front hood came unlatched and was flung backwards by air pressure into the windshield. It also made a dent of at least six inches in the roof of the passenger compartment, but it remained attached to the hinges. The glass on the windshield shattered, but it stayed together. This video is what it felt like from the inside. However, we were going much faster, and both the windshield and hood were obviously beyond repair.

Cheryn screamed in terror, but she quickly regained composure. We were very fortunate to be quite close to an exit. Bill and I rolled down windows and gave Cheryn driving instructions to get the car onto the exit ramp and then into a service station.

Cheryn called the university and reported the problem. The people at the motor pool insisted that one of us had opened the hood for some reason and failed to latch it. We all insisted that no such event had occurred. After a few hours someone brought us a different car to use, and we continued on to the tournament without further incident.

The resolution for 1969-70 was that the federal government should grant annually a specific percentage of its income tax revenue to the state governments. I think that we ran the same case all year. It called for granting 50 percent of the income tax revenue to the states through existing grant-in-aid programs. We claimed that Congress would never finance the programs to that extent because of the power of the Military-Industrial Complex.

I do not remember details from too many tournament. I remember attending the Ohio State with Dean. We had been doing pretty well for the first seven rounds. In the eighth round, however, Dean got all flustered in the 1AR, and totally made a mess of things. His speech was so bad that there was no chance of winning after that. It was too bad, because we would have qualified for the elimination rounds if we had won.

I am not sure where we were, but at one tournament Juddi arranged for us to eat supper with the debaters from Emory University in Atlanta. She liked their southern charm. At dinner she ordered a steak well done. The waiter brought it. Juddi cut it and sent it back for more cooking. She judged that the substitute was sufficiently dead. She smothered it in red sauce. Before she could take a bite one of the Emory debaters asked her very politely why she didn’t just order a piece of bread and cover it with ketchup.

By the middle of November Juddi had changed the pairings so that I was again with Bill. On Thursday November 22 we drove to Chicago for a tournament at UICC. It was a fairly important tournament for us, but it meant that we would miss the last game of the football season.

Students at U-M were allotted one reduced-price season ticket on the south and west sides of Michigan stadium. I had a superb ticket on the 50-yard line. How I managed to get such a good seat is described here. On this occasion I gave my seat away to someone. I don’t remember who received it.

We missed the best game in the storied history of Michigan football. Ohio State was rated #1 in both polls. Michigan was 7-2. OSU had never been behind at any point in any of their previous games. Nevertheless, Michigan prevailed 24-12 that Saturday and won a ticket to the Rose Bowl for the only time in my undergraduate career.

Meanwhile, Bill and I had our worst tournament ever. For me the worst aspect was our loss to my old friend and high school debate partner, John Williams, who represented UMKC. I was more depressed about this than about any previous result. Still, I only had one semester left, and I resolved to make the most of it.

Where are my U-M debate partners in 2020?

On Twitter I follow Bill Black, who is rather famous for finding fraudulent activity in corporate and political America. He currently teaches law and economics at UMKC. His Wikipedia page is here.

I have not been in touch with Gary Black. I was quite surprised to find this web page on the Internet. I am not positive that this is the Gary Black that I knew, but the age and colleges match. I wonder what Charlie Delos would think of Gary’s new career.

Alexa Canady is a famous neurosurgeon who is now retired and living in Pensacola, FL. I emailed her because I noticed that she was a member of the American Contract Bridge League (ACBL). She responded to the email, but we have not had any further correspondence. Her Wikipedia page is here.

I have seen Bill Davey twice since I graduated in 1970. When I came to Ann Arbor after being discharged from the army, he let me crash in his apartment for a week or so. I also saw him at a debate tournament at Georgetown in the mid-seventies. He was then clerking for Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart. Later Bill was a big player in the development of the World Trade Organization. He is now retired from his teaching position at the University of Illinois. His biographical information is here.

Mike Hartmann is an attorney at the international law firm, Miller-Canfield. He was the CEO from 2007 to 2013. His bio page is here. I have been in touch with him by email.

Lee Hess is the Chairman of Cairngorm Capital and lives in Columbus, OH. I have communicated with him by email a few times. His bio page at his company is here.

Bob Hirshon is a professor at the U-M Law School.

I have not been in touch with Dean Mellor. Apparently he is doing something in sales in the L.A. area. His LinkedIn profile is here.

I have not been in touch with Larry Rogers.

1. Bill was a Presidential Scholar in his senior year of high school (1967), which indicates that he had one of the two highest scores in the state of Michigan on the National Merit exams.

2. I asked Roger why Mark Arnold hated me. He told me that I was right about that, but he did not know why. Roger was an interesting guy. He sold bibles in his youth. He tried to teach us to yodel, which he insisted was the best way to prepare for debates. He spent thirty years as lobbyist, mostly on immigration issues. I almost went to see him when he was leading a seminar in Hartford. In 2020 he is an adjunct professor at Vanderbilt.