Rocky and friends Continue reading

In 1988 Rocky and Jake, the two cats that had adopted us as caretakers a couple of years earlier, made the move with Sue and me from Rockville to Enfield. After spending their first winter indoors in Rockville, they had been allowed to roam in the neighborhood of the Elks Club. They always came back to one of our doors when they wanted food, shelter, or a massage. They seemed to have learned what was dangerous, although for Rocky earning the knowledge probably knocked him down to eight lives, as explained here.

Neither seemed to have much difficult adjusting to the change of scenery. There was so much more for them to explore, both inside and out. Rocky particularly liked the fact that when he was outside he could leap up to the windowsill near the dining area and gaze through the window at the activity going on inside. After we started opening the window for him when he did so, this became his preferred form of ingress. Rocky was a real leaper. None of our other cats ever attempted this feat.

Rocky loved to be petted. His favorite technique was the full-body massage, but he would accept any kind of petting by just about anyone whom he knew well.

Jake was a much more private cat. He always seemed to pick a corner and sit there silently analyzing the situation. He tolerated a little petting as the price to be paid for a constantly full bowl of Purina Cat Chow.

The night of October 31, 1988, was a sad one. Sue and I went out for supper, as I remember, and when we came back we found Jake’s dead body on the street. I buried him in the yard, but I don’t remember where.

Sue and I did not feel devastated at Jake’s demise. We had lost quite a few pets by that time. We liked Jake, and we missed him, but neither of us had formed a strong attachment to him.

I don’t remember where our next pet, Buck Bunny, a very large grey and white rabbit with long floppy ears, came from. I am quite certain that I had nothing to do with the acquisition, but Sue had no recollection of us even having a rabbit during this era until I showed her his photo. Buck’s home was a large wire cage in the westernmost small bedroom. The barnboard bookshelves were also in that room. It was a sort of library, but it held as many games as books.

We kept Buck in his cage most of the time because, like most rabbits, he had an instinct to gnaw on things. Before we released him from the cage, we placed all electrical cables up out of his reach. That was possible because, unlike Slippers (described here), he was not much of a leaper.

Sue visited her friends Diane and Phil Graziose in St. Johnsbury, VT, pretty regularly. Sometimes I joined her, but just as often she went by herself. On one of those solo trips she brought home a tiny tan and white kitten. It was so small that it fit in the breast pocket of her flannel shirt. the mandatory state uniform of Vermont.

The kitten was one of many feline denizens of the trailer park in which the Grazioses lived. It probably should have been allowed to nurse for another week or so. However, this was probably the best chance that it would ever get to avoid spending a Vermont winter outdoors. The situation worked out well. We gave him milk for a few days, and then he found the bowl of Cat Chow and the water bowl on his own.

Rocky had little use for the pipsqueak, but the kitten immediately made friends with Buck Bunny. They really hit it off. The kitten liked to sit near Buck’s cage, and when Buck came out they played together or just snuggled.

When the kittne was more mature we got it fixed, of course. By then it had become rather obnoxious, and so we were not a bit surprised when we learned that it was a tom. I named him Woodrow1 after Woodrow F. Call, one of the protagonists of my favorite novel of all time, Lonesome Dove, by Larry McMurtry.

After his medical procedure Woodrow decided that I was his buddy. He loved to take naps next to me. Almost any time that I went into the bedroom and got into bed, Woodrow climbed up to join me.

Meanwhile, Rocky had claimed Sue as his BFF. When Sue and I sat in the living room chairs (purchased used from Harland-Tine Advertising, which is described here, and draped with white cloth) Woodrow sat on my lap and Rocky found Sue’s. The two cats were totally different.

- Woodrow liked all people. Whenever anyone visited us, Woodrow greeted them immediately. Rocky usually hid.

- Rocky loved almost any kind of human food; Woodrow liked only Cat Chow and ice cream.

- Woodrow was a hunter; Rocky preferred to snuggle. He exalted in his full-body massages.

- Woodrow liked to be carried with his back down and all four legs up. Rocky did not mind being picked up, but he insisted on the chest-to-chest method.

- Woodrow liked the top of his head to be rubbed hard, but any other style of petting annoyed him.

- Woodrow climbed trees (although he usually waited to be helped down); Rocky never did.

- Rocky was mostly silent. In his later years Woodrow gave off all manner of soft sounds as he walked around. I called them his “play-by-play”. Except for that one time in the flea bath he preferred not to speak English.

Woodrow and Rocky eventually became buddies. When I returned home after work, they were almost always together on the lawn next to the driveway waiting for me. The sight of them always cheered up, no matter how rough the day had been. I often sang to myself, “with two cats in the yard, life used to be so hard.” Our house was indeed a very fine house.

However, Woodrow did not abandon his first friend, the lagomorph. He still like to lie or sit next to Buck’s cage, and when we let Buck out, the two still socialized.

Actually, they socialized too much. Buck tried to hump the fully grown Woodrow whenever they were together, and Woodrow put up with it. It wasn’t just a phase, either.

Sue and I decided that we needed to get Buck Bunny fixed. I loaded him inside his cage into Sue’s car, and she drove him to the vet. She explained the problem to the doctor. He examined Buck and reported to Sue that “Buck” was actually a female.

Sue asked him why the rabbit was engaging in these activities if he was not even a male. The vet replied that he was only a veterinarian, not a psychiatrist. So, we still let the two buddies hang out together. If the rabbit (who was by then officially renamed Clara, after my mother’s mother, Clara Cernech, who had died in 1980) got too amorous, we just put her back in her cage.

I don’t remember the circumstance of Clara’s death. She was a French Lop, a breed with a lifespan of only five years. She was fully grown when we adopted her.

My favorite moments with Woodrow and Rocky were when I came home for lunch in the summertime. Both cats napped under bushes. Rocky customarily slept in the cluster of forsythia bushes in the northeast corner of our lot. Woodrow favored the burning bush halfway between the house and the driveway to Hazard Memorial School.

I liked to eat my lunch while sitting at the picnic table in the yard and reading a book.When I brought my food (no matter what was on the menu) out to the picnic table, Rocky stumbled groggily out from his resting spot. He sat on the ground next to me for a while and looked up hopefully. Then he raised his front paws up to the bench and nudged my elbow with his snout. Eventually he often leapt up on the table. He knew it was not allowed, but he could not help himself.

I always broke down and gave him a tiny piece of meat. No matter how small the morsel was, he purred loudly while he ate it, got down, and retreated back to his bush to finish his nap.

After lunch I usually took a short nap in the yard on a mat or blanket. As soon as I had made myself comfortable, Woodrow emerged from his bush to check out what I was doing. I always slept on my side. After I had assumed the sleeping position, Woodrow walked up so that he was about a foot from my chest. He then flopped over toward me, and we both stacked a few z’s.

In inclement weather they repeated their tag-team act. Rocky begged for food at the table in the dining area, and Woodrow climbed up on the bed to join me for a nap.

When he was not napping with me, Woodrow moved from place to place in search of the best locations for sleeping. One of his favorite places was on a towel in the small storage area in the bathroom. He arrived there by jumping up on the clothes hamper. He then moved aside the curtain with one of his front paws and sprang into the niche. I called this obscure hidey-hole “Woodrow’s boudoir”. Occasionally when someone used the toilet or the shower, he startled people when he stuck out his head from behind the curtain to look at them with sleepy eyes.

Woodrow preferred Cat Chow to all other forms of food except ice cream. The only time that he paid much attention to Sue was when she sat down with a bowl of ice cream. Then he became more of a beggar than Rocky.

Although Woodrow loved to hunt, he was not possessive about his catches and kills. He often was seen parading around the house with a mouse in his mouth. Sometimes he dropped one at my feet or Sue’s. I had to pick them up quickly. There was a fifty-fifty chance that the poor crittur was still alive. I released many outside; after that they were on their own.

Two were distinctive. One day I was taking my daily postprandial nap in the bed. Unbeknownst to me Woodrow brought into the bedroom his latest prey, a small bird. He silently entered, crawled under the bed with his catch in his mouth, positioned himself directly below my head, and commenced to crunch the bones between his jaws. It was a very disconcerting addition to my dreamscape. Needless to say he left the remains beneath the bed for me to clean up.

On another day I came home for lunch to find that Woodrow had apparently brought home a guest, a full-grown mourning dove. Evidently Woodrow had lost his appetite, but the bird may have thought that he was on still on the menu. He flew about, crashing into one window after another in a panicked attempt to escape. I finally chased him into the library, where I opened the window and closed the door. When I came home after work there was no sign of him. We have never found a cadaver, and so I presume the dove found his way out.

Woodrow was the only pet that we ever had who clearly had multiple personality disorder. His was more like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde than The Three Faces of Eve.

I called Woodrow’s alter-ego Nutso Kitty. Whenever he entered this state his eyes glazed over, and he stalked and attacked anything that moved. One day Woodrow was placidly napping with me when, unbeknownst to me, he underwent the demonic transformation. I must have moved my hand a little. He pounced on it with all twenty of his switchblades extended. After literally throwing him out of the room, I rushed to the bathroom for first aid. My hand throbbed in pain for a few days. Fortunately it was my left hand, which has never been much good for anything except typing.

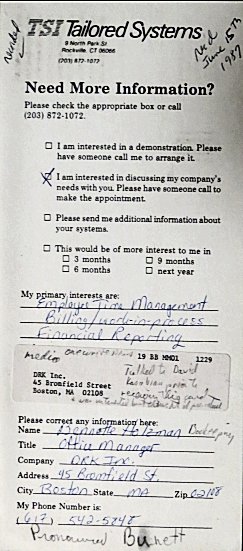

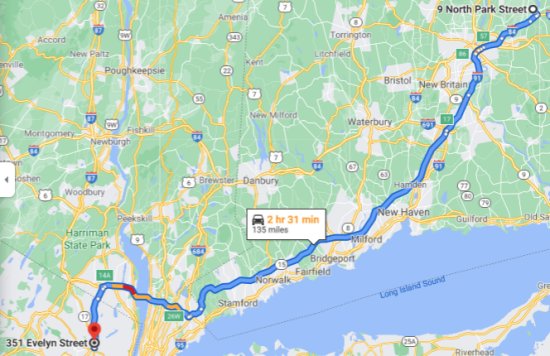

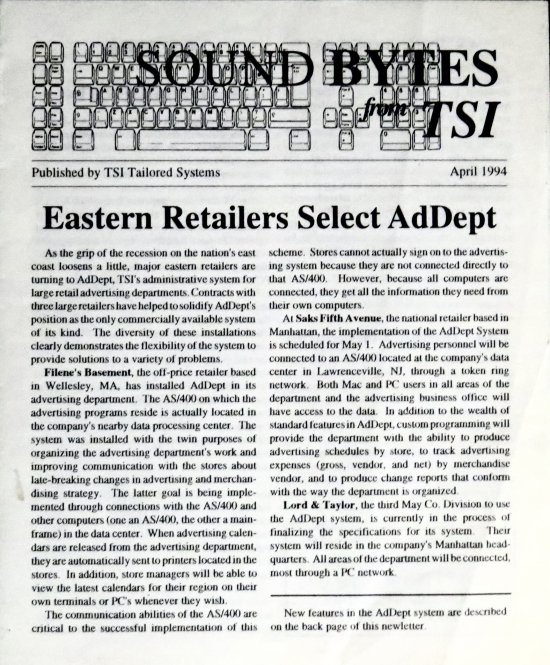

In 1992 or 1993 Sue and I made a trip to Dallas to pitch TSI’s AdDept software system to Neiman Marcus (described here). We then drove our rental car to Austin so that Sue could visit her high school friend Marlene Soul. Marlene exhibited a toy she used to keep her cats active. It was a long very limp stick with a feather on the end. With every slightest move of the hand the cat was drawn inexorably to the dancing feather.

As soon as I got home I purchased one so that I could torture Woodrow. He absolutely could not resist it. After he chased it for at least an hour he hid under a chair so that he could not see it. I pulled it out every time that I thought about that bloody left hand.

We had to take Woodrow to the vet twice to patch him up after fights. Both times he had abscesses that the vet had to drain and then sew up. After the first one, I tried to teach Woody to keep his left up, but he got tagged again a few months later. I never got to see how the other cat did in these scrapes, but I doubt that he escaped without some damage.

I don’t really have many good stories about Rocky. He was consistently a very sweet cat for all of the eighteen years that I knew him. He never got into a fight, or at least he never got seriously hurt. When we brought him to the vet for shots he went completely limp when we put him on the examination table. The vet called him “catatonic cat.”

Once, however, Rocky was missing for three days. Sue and were quite concerned. I had walked up and down the nearby streets looking for him several times. I also took the car and expanded the search area. Sue and I searched everywhere in the house. No luck. However, when I checked the garage for the third time Rocky came slowly out from behind some junk. He followed me inside and nonchalantly drank some water. Within a day he showed no sign of any problem.

How, you may ask, could the cat have hidden in the garage? Why not just pull out the car and search thoroughly? Well, there was no car in the garage. It was full of Sue’s junk, packed from floor to ceiling, as is her new garage as I write this. A thorough search of the garage would have entailed taking all of the junk out piece by piece and piling it somewhere on the yard. Then, whether I found him or not, I would have had to reassemble the mess in precisely the way that I found it.

I did call for Rocky each time that I opened the garage door, but he must have been asleep or just obstinate.

Both Rocky and Woodrow stayed outside a great deal during the summer. They both were tormented by fleas every year. I felt great sympathy for them. They were obviously suffering terribly. I tried to help them.

- I tried to pick the fleas off. During each session, I slew several dozen by squeezing them between my fingernails. I could hear their shells crack, but a few days later there would be just as many.

- I tried flea collars. Rocky, who must certainly have had a set of bolt-cutters secreted away in the bushes, always showed up without it within a few hours. The collar helped a little with Woodrow, but there was no guarantee that the fleas would cross it. He also hated the collar, but Rocky would not lend out his tools.

- I tried flea powder. It helped a little for a short time.

- Flea baths actually worked, but both cats hated them. After a short struggle Rocky submitted meekly, but he also gave me a look that asked what he had done to make me despise him so much. Woodrow, of course, fought me tooth and nail. I had to don gloves and my army field jacket to pick him up. One time—I swear that this is true—he clearly screamed out the word “NO!!!!” as I dipped him in the medicated water in the tub.

Of course, if we did not attack them quickly, the fleas got in the carpet, and, after we got them off of the cats we had to “bomb” the house. That was not a bit pleasant.

Fortunately, the flea problem was solved when our vet supplied us with Frontline2, the monthly drops on the back of the neck, at some point in the nineties. I don’t know if there were side effects, but the product sure worked on the fleas. It was great having flea-free cats and a flea-free house.

Not long after Woodrow established residency with us, I bought a cat door and installed it in a window that led to the top of the basement. It was located just below the bathroom window. Just below the window on the basement side was the top of some shelves that were there when we moved in. From the shelves I placed a spare door at a 45° angle to serve as a ramp down to the ping pong table. A box served as a step up to the table or down to the floor.

Rocky seldom used the cat door. He preferred for a human to let him out through one of the doors or in through his favorite window. When he did enter through the cat door, he did not use the ramp. Instead he jumped from the bookshelves to the washing machine and from there to the floor. He exited the house by jumping up on the picnic table and climbing the shelves.

Other cats occasionally tried to use the cat door. Brian Corcoran gave me his Super Soaker, which proved to be very effective at chasing them away. However, the felines were most active at night, and I was not. Occasionally one would get in and help himself to some Purina Cat Chow.

I often heard the distinctive caterwauling of two or more cats that were about to engage in that furious and bloody activity known as a catfight. Once I saw Woodrow in the basement on the bookshelf near the cat door loudly warning a cat not to poke his head through. He definitely meant business. His body was crouched and taut, ready to for action. His right paw was raised with all five claws drawn. He reminded me of Horatius at the bridge.

There were a couple of other uninvited guests. One night I heard some very loud munching coming from the hallway. I jumped out of bed, turned on the hall light, and beheld an opossum helping himself to the Cat Chow in a bowl at the other end of the hall. I assume that the opossum was a male since it did not have a dozen babies on its back.He had evidently found his way through the cat door, down to the basement, and up the stairs. My footsteps frightened him enough that he rushed down the stairs, never to be seen again.

The story of the other remarkable intruder can be read here.

Sue and I took quite a few long trips after Rocky and Woodrow moved in, and the cat door was installed. We also invested a few dollars in a gravity-fed Cat Chow dispenser. Whenever we took a trip we left Rocky and Woodrow “home alone”. We provided them with plenty of food and water, and Sue arranged for someone to check on them every few days. This arrangement worked well for our trip to Texas (described here), our cruising tour of Greece and Turkey (described here), our trip to Hawaii in 1997 (described here), our misbegotten adventure in Maine and Canada (described here), and our first tour of Italy in 2003 (described here).

Rocky died later in 2003 at the age of eighteen. I am pretty sure that he used up all nine of his allotted lives. Even though I was much closer to Woodrow for the many years that we had both of them, I cried when Rocky died. He was so tough and such a nice cat. I really missed him.

The story of the Enfield pets continues here.

1. A better choice probably would have been “Augustus”. His personality was much more like the free-spirited Gus McCrae’s than the rigid Woodrow Call’s.

2. I later switched to Advantage II. It was cheaper and worked better.