A tragic tale of two millionaire wannabes: the Saudi terrorist, the cowboy president, and what they wrought. Continue reading

I wrote this entry on September 11, 2001, the twentieth anniversary of the famous terrorist incident. 9/11/01 was a Tuesday. We had a full house at TSI’s office in East Windsor—Sandy Sant’Angelo, Nadine Holmes, Harry Burt, Brian Rolllet, Denise Bessette, and myself. Sandy either was either listening to a radio, or she was surfing the Internet. She told the rest of us. I cannot remember whether everyone stopped working or not.

I was not even a little surprised that something like this had happened. I had followed developments in the Middle East since I debated and gave extemporaneous speeches about foreign policy when I was in high school. Also, there had already been some close calls. In 1993 a member of a group called Al-Qaeda, Ramzi Yusef, had set off a very destructive bomb in a basement parking lot of the World Trade Center.

For a long time Arabs who were not lucky enough to control oil deposits had been treated very shabbily by the West. The big issue, of course, was the fact that after World War II the Palestinians had been summarily evicted from the land in which they had resided for decades and replaced by Jewish refugees from the Pale and from western countries. At the same time Israel had been assisted by the United States in developing a very strong army with an impressive arsenal that included nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them.

Little by little the Israeli government had limited the rights of non-Jews and, after the Six-Day War in 1967, had authorized hundreds of thousands of settlers to seize property on the West Bank previously owned by the Palestinians. Another factor was the fact that one of Islam’s holiest places had also been seized during the war and access to it was subsequently controlled by the Israelis. On several occasions a peace negotiations between the two sides had been attempted, but nothing much ever happened.

For more than fifty years any attempt to address these issues in the United Nations was thwarted by the U.S. So, it was no surprise to me that a very large number of people in the Middle East felt great animosity toward America.

In 2001 and the previous few years I had been traveling all over the country1, almost always by airplane (anecdotes recounted here). I was lucky that most major airlines scheduled flights at the local airport, Bradley International, but almost all my itineraries required a layover at a hub. So, I was quite familiar with the security arrangements at airports around the country. At most airports security was run by the airlines themselves or by contractors that they hired. The marketplace for air travel was intensely competitive. The primary objective for the airlines was to make the experience enjoyable.They emphasized how pleasant flying on their planes was. Security was seldom mentioned.

In the hours that I spent sitting in airports I sometimes tried to imagine ways for getting weapons onto airplanes. The type of security varied greatly from airport to airport, but I thought that a determined person could easily have figured out a way to get a gun on an airplane. In some airports, such as Kansas City’s, it would have been laughably easy.

So, when I heard on 9/11 that a group of people had skyjacked some planes, I assumed that that they had smuggled guns aboard. In fact, however, they did not need guns. Their only weapons were box-cutters, mace, and imaginary bombs. They were able to commandeer the planes because in those days the door to the cockpit was generally open. Flight attendants went in and out all the time. It was also not rare for the captain to meander into the passenger area and chat with people. Kids were sometimes invited to visit the cockpit. The airlines encouraged this rapport between the crew and the customers.

On 9/11 nineteen men divided into four teams. Two teams went to Logan International Airport in Boston, and one each to Newark International and Dulles in Virginia. Each group intended to board a flight,and when it had reached cruising altitude, and take control of the passenger area and then the cockpit. The one member of each group who had some training as a pilot would then fly his plane to a designated targets and crash int it. The four events were designed to occur simultaneously or nearly so.

Fifteen of the men were Saudis, one was Egyptian, two were from the United Arab Emirates, and one was Lebanese. Four had some training as pilots. The others were simply there as “muscle” to keep the passengers and crew under control. The oldest was the Egyptian, Mohamed Atta, who was thirty-three. All the rest were in their twenties.

Two morning flights each were selected on American Airlines and United Airlines. Three of the attempts were successful. At that time the standard procedure in dealing with a hijacker was to accede to the demands. In this case the demands were simply for the crew to get out of the way and for the passengers to remain in their assigned seats.

The passengers on United Flight #93 revolted. What happened after that is unclear, but the plane crashed in Pennsylvania.

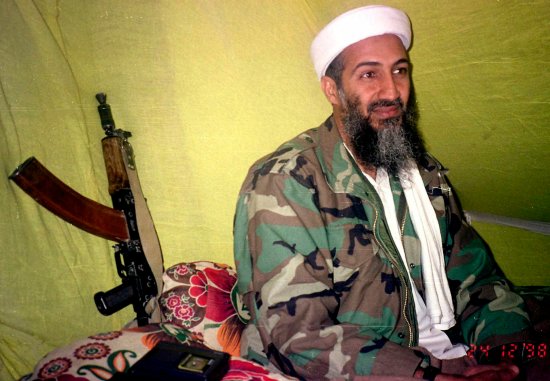

The event was merely a murderous stunt, not an attempted coup. Al-Qaeda claimed credit for the attack, and intelligence briefings had actually predicted something like what had occurred. Most of the 2,997 casualties were associated with the attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

My representative, Nancy Johnson, immediately declared that “9/11 changed everything.” Most people probably agreed with her, but to me the only thing that 9/11 changed was to remove the blinders concerning airport security. The other potential lesson, that U.S. foreign policy was bitterly hated by a large swath of the world’s population, was not learned. In fact, anyone who acknowledged it was reviled. Instead, the clarion call was “United we stand!” Criticism was not tolerated.

The Bush administration’s reaction was very strange in one way. The entire country’s airspace was essentially closed to commercial traffic for several days. That was probably prudent. However, during this period the government allowed the evacuation from the U.S. of 140 or more Saudi nationals despite confirmed intelligence that the vast majority of the of the perpetrators were Saudis. The funding also mostly came from other Saudis.

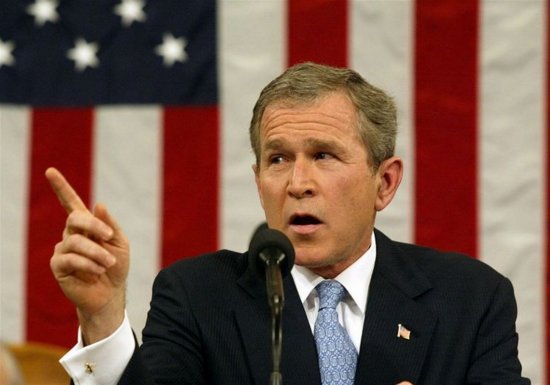

The attack was described by everyone as a terrorist act, which, of course, it was. Colin Powell said that we were “fighting a war against terrorists of global reach.” He therefore excluded Hamas, Hezbollah, and domestic terrorists. Almost immediately, however, the “of global reach” limitation was dropped, and anyone who in any way supported terrorism (except for the right-wing American version) was added to the list of enemies. Later the president the target as evil itself, as embodied in the “Axis of Evil’: Iraq, Iran, and North Korea. Bush even used the word “Crusade” to describe the new Bush Doctrine of boundless preemptive military actions. No word was more offensive to Muslims.

To his credit, W. stopped short of offering indulgences to everyone who fought in this war on terror.

The testosterone-laden approach was very popular. Support for the president jumped to an astounding 90 percent. Nobody asked me.

This is indisputable; None of these countries had in any way participated in the attacks. Iraq’s biggest crime was probably the $25,000 that Saddam Hussein had been paying families of Palestinian suicide bombers. There was something personal, too. Iraq had allegedly been behind an assassination attempt on W.’s father in Kuwait. Iran was allied with Hezbollah. The Israeli lobby and the Neo-Cons who advised Bush pressed for aggressive action against both.

Nobody in North Korea ever crossed any borders. Who knows what the justification was for including them in this unholy crusade? It has been reported that President Bush informed Bob Woodward that he loathed Kim Jong Il.

So, who was a terrorist? Terrorism is a tactic, not a country or organization. Terrorists didn’t wear uniforms or work on behalf of governments. Some didn’t work for anyone. Their common traits were strict secrecy and lack of access to advanced weapons.

So, how do you identify them before they commit a heinous act? The answer was simple: “Don’t worry. We know some of them3, and we have ways of finding the rest. Trust us.”

Meanwhile, the first stage was to attack the Taliban, a band of religious fanatics who ran Afghanistan and gave refuge to Osama Bin Laden, the leader of Al-Qaeda. After a few weeks of heavy bombing the Taliban offered to hand Bin Laden over, but the Bush people were unwilling to negotiate. They expected a quick unconditional surrender, which, of course, never happened. If you look up “hubris” in the dictionary, you might see a picture of Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney.

In 2003 the U.S. attacked Iraq. The administration had made a comical attempt to gather allies for the vengeful invasion of the country that was the most secular of any in the Muslim world. An attempt was even made to convince the United Nations to back the attack.That was thwarted by Pope (Saint) John Paul II. My dad was very upset by the fact the country that he loved and for which he had fought in World War II, would commit such an act of naked and illegal aggression.5

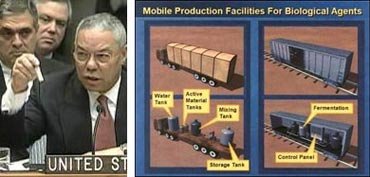

I remember watching a video recording of Colin Powell’s presentation to the U.N. I had read a transcript and had been somewhat impressed. However, when I saw the video I realized that what I had assumed were photos presented in evidence were actually drawings. He was trying to sell an unprovoked invasion based on an artist’s conception of what the Iraqis might have been doing. These were just cartoons! Although many Americans swooned, the rest of the world was unimpressed.

Most of the American public bought all or at least most of the lies. I knew from reading Juan Coles’ blog, Informed Comment, that the case presented was full of holes.

The administration was not impeded by this snub. Condoleezza Rice and others appeared on radio and television programs to promulgate a new catchphrase. Even if Iraq did not currently harbor terrorists, it certainly had “weapons of mass destruction” and if the country ever did start welcoming terrorists, we did not “want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

In point of fact, no one (except perhaps Cheney in his yellowcake fantasy) thought that Iraq had nuclear weapons. Some people just assumed that Saddam Hussein had been lying when he declared that his government had destroyed all of Iraq’s chemical weapons. The WMD justification was totally bogus.

No one except Harry Shearer seemed to notice that the one Islamic country that definitely possessed weapons of mass destruction and definitely had harbored terrorists, Pakistan, was never mentioned in this propaganda blitz.

There is no doubt whatever that the Republicans (joined by a few turncoats like my senator, Joe Lieberman) knew exactly what they were doing. Bush informed a stunned Tony Blair on September 14, 2001, that they planned to attack Iraq.

What really made me see red was the indefinite imprisonment of foreigners on the military base in Guantánamo Bay for the sole purpose of circumventing the American system of justice. Some were never even charged with a crime.

The interrogators even tortured civilians—some captured by very sketchy foreigners—to force them to provide evidence of Iraqi misdeeds. Even worse was the disgraceful use of “extraordinary rendition” to send captured individuals to countries with less rigorous legal systems in order to extract information from them—whether or not it was true. This was perhaps the most disgraceful period in U.S. history that I have witnessed. In my opinion all of the participants should have been tried for war crimes. I cannot imagine what their defense would have been.

The reaction to 9/11 that affected my lifestyle the most was the creation of the Homeland Security Department and, especially, its Transportation Security Administration (TSA). Security at airports and on airplanes definitely needed improvement. Armed passengers needed to be prevented from boarding airplanes. If someone with a weapon somehow got aboard, they must be prevented from gaining access to the cockpit.

However, one does not use a double-barreled shotgun when threatened by a mosquito. The new security procedures were a grotesque overreaction. For example, solely because one incompetent idiot named Richard Reid once tried to light his sneakers on fire on an airplane, every adult was required to remove both shoes before boarding an airplane! The TSA transformed air travel from a boring expediency into an outrageously annoying exercise in frustration. I ended every trip in a very foul mood.

European countries had already implemented a much more reasonable and equally effective program. We should have sought counsel from them as to how they had successfully dealt with a very active terrorist group, the Red Brigades. The Bushies were too busy making and selling their plans to ask anyone for advice.

The most sensible moves that the administration undertook were to require the crew in the cockpit to stay there and to require the door to the cockpit to be locked. Thank goodness the government did not accede to the demands from some gung-ho pilots to carry sidearms.

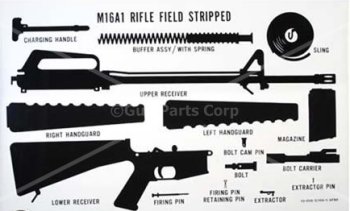

The most frightening experience that I ever had in an airport or an airplane was in the Intercontinental Airport in Houston shortly after 9/11. Some genius had decided that it would be cool to have soldiers with automatic weapons in U.S. airports. I saw in the Houston airport a young guy in U.S. Army camos4 eating his supper alone at a restaurant. His M16 was leaning against the back of his chair.

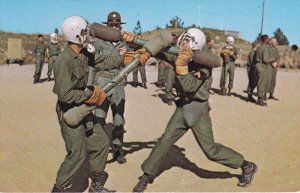

The M16 was a weapon that I (and thousands of others) knew very well. I could consistently hit a human-sized target with one at distances up to three hundred meters. I could take one apart and reassemble it. Most importantly, I knew the location of the little lever that activated the fully automatic mode. As I watched the young man eat his burger, I suddenly realized that I was carrying a potential weapon—my laptop in its very sturdy metal case—with which I could easily disable this soldier, thereby enabling me to seize his rifle. I wondered how many other travelers there had similar thoughts.

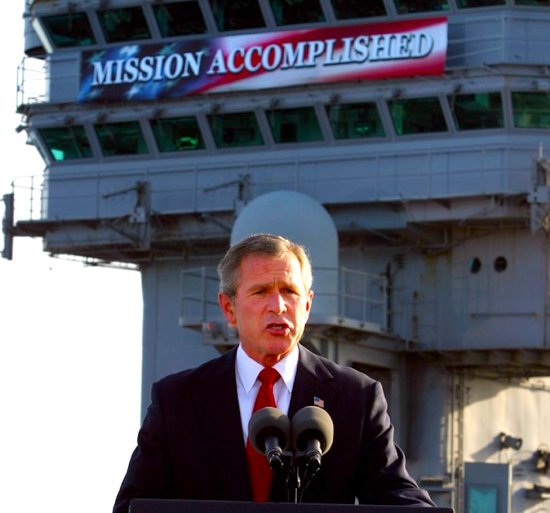

Anyway, the U.S. forces quickly brushed aside the Iraqi troops. Our draft-dodging president got to land a jet on an aircraft carrier where a huge “MISSION ACCOMPLISHED” banner was displayed.

We tried to install a Hartford Native, Paul Bremer, as imperial governor. That did not go over too well. The fighting continued in whack-a-mole fashion at a reduced level. Then the situation deteriorated. We dropped a lot of bombs, and hired a lot of mercenaries. When things began to look really bad again our military presence in Iraq even “surged” just before the 2004 election in America. Some called it “the splurge” because a whole lot of money was spent assuring the support of local power brokers. This tactic was effective, but the loyalty only lasted as long as the payments kept coming.

The U.S. eventually imposed on the Iraqis an Italian-style parliamentary democracy. We may have expected the Iraqis to form parties that resembled liberals and conservatives, but, in fact, Saddam Hussein had probably been the most liberal leader in the Muslim world. He tolerated all religions, but the new parties were formed primarily along religious lines, and, guess what, the most popular party was the Shiite faction that was friendliest to Iran, a card-carrying member of the Axis of Evil. The main thing that all parties agreed upon was that all Americans and practitioners of non-Muslim religions—including the rather vibrant Christian communities—were not welcome in democratic Iraq.

Eventually, we did go, in a manner of speaking. But what a cost this adventure exacted—hundreds of thousands of lives lost, millions of lives of innocent Iraqis disrupted, trillions of dollars wasted, and a treasure trove of international good will squandered.

Then the Islamic State (or ISIS or ISIL) developed, and we allied with Iran, of all people. Then we had to fight them in Syria, too, and …

I don’t want to write any more about this. I am not an expert on the Middle East, but Juan Cole is.

I have been following Juan Cole’s blog, Informed Comment since it began in 2002. You can find it at juancole.com. Cole was (and still is in 2021) a professor in the history department at my Alma Mater, the University of Michigan. His writings presented an impartial and very well researched description of affairs in the Middle East and other countries dominated by Muslims. He had lived for a period in the area and he could read and understand Arabic and a few other languages used in that area.

I have read his blog every morning no matter where I was since he started posting it in 2002.

Professor Cole wrote a long article in 2006 for Foreign Policy magazine explaining the politics of the situation. Although he was pilloried by jingoistic Americans and Zionists at the time, he has proven right about nearly everything. The article was republished on his website on September 10, 2021. You can read it here.

1. In those years I spent considerable amounts of time in airports in all of the following states: Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, DC, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin.

2. Nancy Johnson served in Congress for twenty-four years. She was defeated by twelve percentage points in 2006 by Democrat Chris Murphy despite outspending him by a large margin. Since then she has worked as a lobbyist.

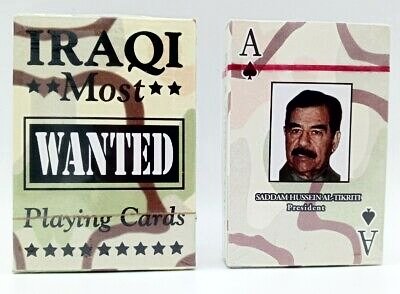

3. To help identify the “bad guys”, a deck of cards was created. Saddam was the ace of spades. During this period rumors abounded about potential terrorists who looked like ordinary God-fearing law-abiding citizens. However, on notification by someone (George Soros?) they and the other members of their “sleeper cell” were ready to spring into action to attack a predetermined target.

Some patriots took the “better safe than sorry” approach. On September 15, 2001, Frank Roque murdered a Sikh man and fired on a Lebanese man and an Afghan family in Arizona.

4. My dad asserted at the time that it was the first unprovoked attack by the U.S. This was clearly false, but I never challenged it.

5. Don’t get me started on the current custom of military personnel wearing camouflaged fatigues for day-to-day activities in the U.S.