More of the same and a tasty side dish. Continue reading

I arrived at Wayne State with a masters degree in speech communication from Michigan. If I wanted to get paid to coach debate, I had to be a graduate student. Since I already had a masters, that meant that I needed to commit to work towards a PhD.

PhD candidates were required to take a given number of additional graduate-level classes. A few had to be outside of the department. Repeating classes in the same basic subject taken at other institutions was perfectly acceptable.

A dissertation was also required. The basic requirement was that it include original research in an important topic under the aegis of speech communication. My unhappy experience in that endeavor is described here.

PhD candidates at Wayne State were required to make three oral presentations. The audience for all three was the student’s committee of “advisers”, which consisted of three professors from the speech department and one from another department. The advisers could ask questions, make statements, and suggest improvements. At the end each presentation met and told the candidate whether he passed or failed.

The required presentations were these:

- The oral examination. The outside adviser was not included in this exercise. Each adviser could ask any number of questions about any subject.

- The defense of the prospectus for the dissertation. The prospectus is a printed document that outlines the purpose of the study, the plans for research, and the method of evaluation.

- Defense of the dissertation.

In general, Michigan is a much more demanding school than Wayne State. These figures are from 2019:

| Acceptance | Graduation | |

| Michigan | 23% | 91% |

| Wayne State | 73% | 38% |

This does not mean that every department at U-M was better. I was not favorably impressed by the faculty in my area of the speech department at Michigan. My favorite teacher at U-M (Dr. Cartwright) was in the psychology department. The one impressive person at U-M’s speech department (Bob Norton) did not take teaching speech seriously. I would say that the speech professors at Wayne State were slightly better.

The graduate students in speech communications at both schools impressed me equally little. Practically none of them would have been able to handle a rigorous curriculum, as in a math, science, or language department. I studied the bare minimum amount to get by, and I had no difficulties with any of the classes.

I think that I took at least one class from every professor who resided on the fifth floor except George Ziegelmueller1, who had been in the department for ages. I don’t remember George teaching any graduate-level classes while I was at Wayne State. If he did, it was probably in directing forensics.

Here are my impressions of the other teachers. They are listed in alphabetical order, with the ones whose names escape me at the bottom.

I think that Steve Alderton2, whose first year was 1977-78, taught a class in group communication. I don’t remember much about it. Steve got his PhD at Indiana, which had a very good reputation in speech circles.

Both George and Steve were on my dissertation committee. That experience is described here.

I remember taking a class from Jim Measell3, but I don’t remember what the subject was. Sheri Brimm was in the class with me. That experience is described here.

In July of 1979 the Skylab satellite fell into earth’s atmosphere and broke into a lot of debris. Jim removed a ceiling tile from over his desk and scattered some fairly realistic-looking electronic parts around his office in hopes of persuading people that pieces of the satellite had crashed through the roof of Manoogian.

Barb O’Keefe3, earned her PhD at the University of Illinois, a gathering point of disciples of George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory. I think that her husband was also a devotee. She taught a class in communication theory, in which she described the “evolution” of communication theory. The second-to-last step was systems theory, which she dismissed because a system is never truly closed. Of course, that is true. The researcher tries to exclude externalities when possible and account for them when it isn’t. However, the externalities exist regardless of which construct is used to analyze the transactions.

The culmination, according to Barb, was PCT, which postulates that people have dichotomous (i.e., two dimensional) constructs that they use to evaluate everything. Examples are light-heavy and tall-short. I asked her about colors, and she replied with something like, “Oh, there’s an answer to that.” She never looked it up or told me where I could find it. She was quite intelligent and an effective teacher, but she was also a “True Believer”, and that scared me.

She also really upset me when she let slip that she thought that debate training “turned students into monsters.” I kept my distance from her.

I remember taking one seminar from Ray Ross5, the author of the Speech 100 textbook. It might have been about persuasion. All I remember is that it was the least demanding of all of the courses that I took, and everything that he taught was at least twenty years old.

Lie Ray, Gary Shulman received his PhD from Purdue. I took two of his classes. The first was statistics, which covered much of the same material as the class that Bob Norton taught at Michigan. The number of students enrolled was more than for Bob’s class. I remember that everyone was assigned a topic to explain to the class. Most of these topics were very straightforward, but the one that I was assigned was a complicated statistical tool that I had never heard of. I spent a lot of time working on my lecture, but it was just impossible (IMAO) to present it in a fashion that was comprehensible for speech students within the time limit, which I think was fifteen minutes. I got a bad grade on this exercise. This was the only time in my life that I complained about a grade. It didn’t matter; I aced the tests.

Gary’s other class, which, as I recall, was taught at night, was industrial communications. Vince Follert and Pam Benoit were also in this class. We had several exercises to perform as teams of three or four. The catchphrase was “Learn by doing”. The first project challenged each team to construct a castle using some tools that each group was provided—a stapler, some tape, string, some crayons, and construction paper. The castles were then judged on sturdiness, height, and esthetics.

Pam, whom I knew to be a good artist, was in our group. I gave all of the construction paper and crayons to her and told her to decorate them so that we did not finish last in esthetics. The rest of us then affixed one end of the string to one of the ceiling panels next to a wall. We then stapled the decorated paper to the string and taped the whole contraption to the wall. It looked nothing like a castle, but it was by far the tallest, easily the sturdiest, and as esthetically pleasing as any. De gustibus non est disputandum. We won the competition, but Vince claimed that we cheated.

In the second, much longer exercise, we had different roles in a factory that made some doodads from tinker toys. I was the foreman in the first segment. Gary never prohibited us from rearranging the furniture, and so I ordered that the desks of the people who were charged with locating the pieces moved so that they were next to those of the people who assembled them. This made everything very efficient and made the rest of the exercise, which culminated (on Gary’s order) in a strike of employees who were as jolly as Santa’s elves, totally inappropriate.

I had heard through the grapevine that getting a consulting gig with one of the auto companies was the Holy Grail for the faculty members in the speech and psychology department. I never found how many, if any, completed the sacred quest.

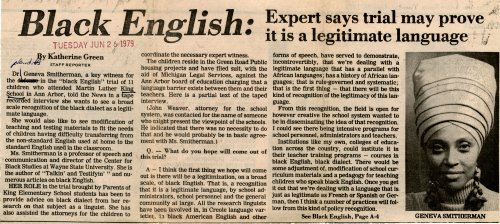

I am pretty sure that I never met Geneva Smitherman7. I may not have even seen her. I have no recollection of where her office was. She definitely taught classes while I was at Wayne State. However, I never took any, and nobody that I knew well did either.

A surprisingly large number of graduate students in Wayne State’s speech department held outside jobs. A fairly large portion of this group took all of Prof. Smitherman’s classes and very few others. One of these students took the class that Ray Ross taught that I was in. She confided that she had many friends who would not take classes from any of the other professors. It was actually feasible to get a masters degree at Wayne State using this approach. If the student was willing to write a thesis (supervised by Prof. Smitherman), it could be accomplished in only a few years.

The effect that Prof. Smitherman and her ideas had on the department as a whole is discussed here. Jimmie Trent was the chairman of Wayne State’s speech department up until 1972 or 1973. I don’t know when Prof. Smitherman was hired, but it is fun to speculate that Jimmie hired her as a parting gift to the department. She is eight years older than I am. The timing could be right.

There was also a professor in the department who taught classes in rhetoric and oratorical analysis. I am not certain whether I took any of them or not. I definitely remember that he brought his adolescent son to our house on Chelsea one evening to witness one of our D&D adventures. We would have let them join the party of adventurers—I had a computer program that could generate a character in seconds and generate a nice printout with all of the characteristics. They declined the invitation.

I took one graduate-level class in psychology. I don’t remember the professor’s name, but he was both entertaining and handsome. I was more interested in the first characteristic than the second, but I did notice that about 80 percent of the students were female. I wanted to ask this professor to be the “outside” member of my PhD committee, but he was on sabbatical.

I found the psych students in this class to be no more capable than the graduate students in the speech department. I received an A with very little effort.

In one class session the psych professor discussed oral exams. He said that it was very difficult for the faculty members to assess the performance of the candidates. In general, they were mostly surprisingly awful. He said that some professors used a 10 percent standard. That is, if 10 percent of the answers seemed acceptable, that was good enough.

He also mentioned an exception. He told us about one fellow who was not considered a very good student. However, his performance in the oral exam was the best that any of the professors had ever witnessed. It turned out that he worked as a disk jockey (whoops; the meaning of that term has changed in the intervening years) “presenter” at the college’s radio stationed, and he was used to ad-libbing and responding to unexpected questions.

Well, if a little radio time had that effect, I figured that all my years of debate experience would certainly serve me even better. I did not waste even one hour cramming for my orals, and I passed with flying colors.

I took one other class; I cannot even remember the exact nature of the subject matter. It might have concerned statistics for the social sciences or the the use of computers in social science research. The instructor was weak. I remember that on one of his multiple-choice tests he asked for the definition of an algorithm. When he graded the test he marked the right answer (a set of rules to be followed in calculations or problem-solving) wrong and refused to admit that it was a mistake. I might have dropped the class or just stopped attending.

You may be wondering how a student could have “just stopped attending”. Well, the university had a requirement that the prospectus be presented and defended before completing the coursework. I don’t remember the details. I was not ready to write my prospectus on time, and, besides, I was busy coaching debate. So, for a semester or two I attended classes for which I had not registered. This was not the smartest scheme that I had ever devised, but, since I did not pay tuition either way, I could not see that it would harm anyone.

I do not understand why none of my instructors challenged my presence. I am quite certain that the university provided every instructor with a roster of all enrolled students.

Occasionally someone who was not on the roster attended one of the classes that I taught. I took attendance every day and, in a friendly way, challenged all the interlopers. Occasionally they were just guests of one of the enrolled students8. None of the people whom I challenged ever came to a second class.

My failure to enroll went undetected for quite a while. When someone in the administration finally noticed I was ordered to report to the dean’s office. He grilled me about why I did this. I told him frankly that I had no excuse, but I wanted to do whatever was necessary to get back in good standing. He grilled me about this over the course of a handful of interrogations. He apparently thought that my actions were part of a nefarious scheme.

I discovered during these exchanges that the school was reimbursed by the state based on enrollment numbers. So, what I did cost Wayne State some money. Of course, it also saved the state of Michigan the same amount of money.

I also had to go to track down the instructors and ask them to submit grades for me. Fortunately they were all still on campus. None of them gave me the slightest bit of grief.

Of course, if I had stopped attending a class because I could no longer tolerate it, I just never asked for a grade. I had plenty of credits without those classes.

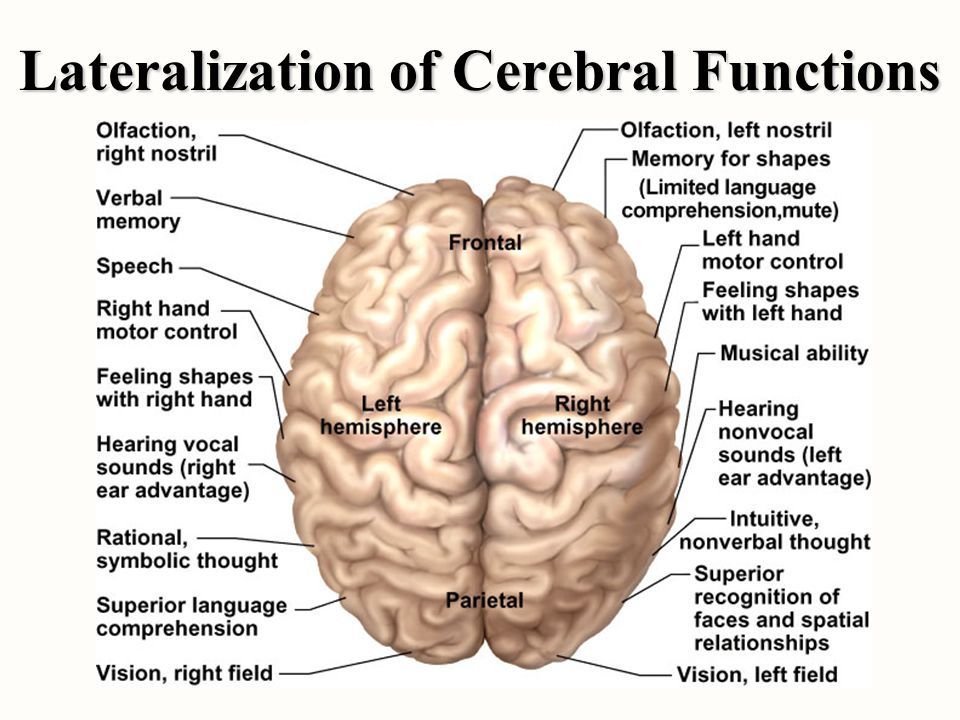

I spent a lot more time researching than I did studying for these classes, which for the most part, I considered useless. None of my research concerned anything that I had studied in classes at Wayne State. It was concentrated in two areas: 1) the social science research that used the ten standard questions in the “shift to risk” research, and 2) the medical research concerning hemispheric specialization. The former was compiled in anticipation of doing a dissertation on some aspect of the area. The latter was because I was intellectually curious about the subject. In the late seventies almost no one outside of the medical community was aware of all the recent breakthroughs in understanding the function of the brain.

There was no Internet; there were only libraries. I had boxes full of 3″x5″ file cards on both subjects. I used the “shift to risk” file to prepare my prospectus. I used the hemispheric specialization data for a paper that I submitted in 1980 to the Journal of the American Forensic Association9. I wrote it in response to a two-part article in the journal by Charles Arthur Willard10 (whom I knew as the debate coach at Dartmouth College) entitled “The Epistemic Functions of Argument: Reasoning and Decision-Making From A Constructivist/Interactionist Point of View”.

I knew that Dr. Willard, like Barb O’Keefe, received his masters and PhD degrees from Illinois in the speech department that promulgated Personal Construct Theory. My paper presented a short review of the current state of the neurological evidence about the way that the human brain makes decisions. It argued that some of the fundamental elements of PCT were inherently inconsistent with the fundamental postulates of PCT.

Before sending my paper to the same journal I let George read it. He agreed with me that people in communications theory were not conversant with research by neuroscientists. He asked me if I was sure about “all of this”. I assured him that when something was questionable I had been careful to include disclaimers.

My paper was quickly accepted for publication, but the principal reviewer wanted me to make a few minor changes. By then, however, I had decided to change careers. I let it drop.

1. George died in 2019. A press release from Wayne State can be read here.

2. While writing this I discovered that only a few years after I departed in 1980 Steve Alderton changed careers entirely. He got a law degree and then became (for almost three decades) an official of the federal government, a world traveler, and an artist! His obituary is here.

3. Jim Measell left academia in 1997 to specialize in public relations. His experiences are described here.

4. Barb O’Keefe Northwestern https://dailynorthwestern.com/2019/08/14/campus/school-of-communication-dean-barbara-okeefe-to-step-down-in-2020/

5. Ray Ross died at the age of ninety in 2015. He was at the Battle of the Bulge! His obituary is here.

6. Gary is a professor of strategic communication at Miami University in Oxford, OH. Information about him can be found here. I wonder if Jimmie Trent hired him.

7. It appears that Geneva Smitherman is now at Michigan State. Here is her Wikipedia page.

8. The most memorable of these occasions was when one of the students brought her identical twin sister. This was the same student who started one of her speeches with, “I want to take this occasion to introduce all of you to my best friend, Jesus.”

9. The journal’s title was later expanded to Argument and Advocacy: the Journal of the American Forensic Association.

10. Charlie Willard has a Wikipedia page.