An amazing system. Continue reading

In the eighties IBM sold two mini-computers1, the System/36 and the System/38. It was hard to understand why. They both supported the same programming languages (RPG, COBOL, and BASIC), cabling, and peripherals. They both were aimed at small businesses that used them for traditional “business” applications—as opposed to graphics or calculation-intensive jobs. There was a large overlap in the targeted customers for each system. Both systems were even designed at the same IBM facility in Rochester, MN.

For several months rumors abounded in the trade magazines for these products that IBM would soon announce a new computer to replace both of them. The code name was Silverlake.

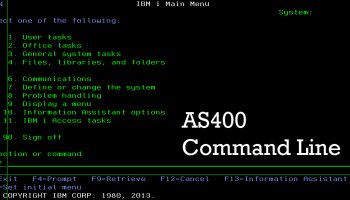

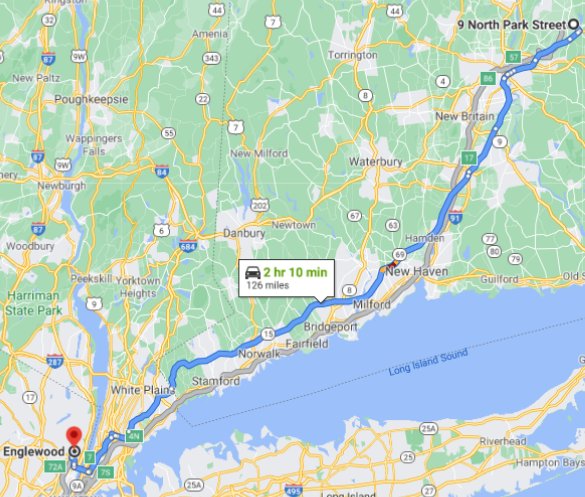

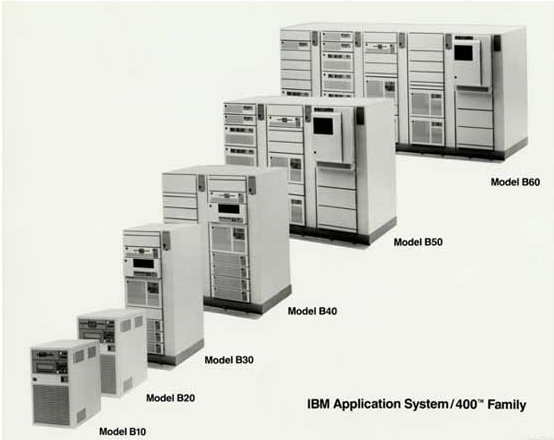

The announcement was made on June 21, 1988. I attended a briefing at the IBM office in Hartford. The name of the new system was AS/400. The “A” stood for “application” because every program ever written for either the S/36 or the S/38 would run on the new system. Neither the S/36 nor the S/38 could be upgraded to an AS/400, but the new system accepted all of the software and most of the peripherals. The thrust of the pitch was that IBM was providing the “best of both worlds.”

This claim was possible because the “native” environment of the new operating system was based on the System/38. The new system also supported a “System/36 environment” that allowed programs written for that system to run with no changes. Since the native environment was much more efficient than the S/36 environment, software developers were expected to migrate their code to the native environment as soon as they could.

My immediate interest was in the price of the low-end systems. I was bitterly disappointed. The least expensive model, the B10, cost much more than the 5363, which was a perfect fit for most of our target market. Once again, IBM just refused to address the millions of small businesses that could be served very well by an economical system that could handle a handful of simultaneous users. In 1987 IBM had finally introduced such a system. With this announcement just one year later a perfectly good solution was replaced by a much more expensive and unproven one.

So, from the perspective of selling to local advertising agencies and other small businesses, the announcement was a nightmare. However, as is described here, Macy’s gave TSI no choice but to embrace the AS/400. They wanted to hire us to develop a system for them, but they had no interest in purchasing obsolete hardware.

IBM’s approach eventually worked out in our favor. The AS/400 had many outstanding features that were not available on the System/36.

- The new system’s operating system was built over a relational database. I am not sure that most people in the S/36 community knew this at the time because IBM did not even mention it at the announcement meeting, and the database was not even given a name (DB2/400) until much later. All anyone knew was that it sure had fast file access.

- The defining feature of the operating system was inherited from the System/38: Single-Level Store. I never have understood this completely, but the effect was that the main processor did not care whether programs or “pages” of data were already in memory. The task of managing storage was managed by other processors. So, the problem that occurred on the System/36 when too many jobs were running simultaneously would not occur on the AS/400. Moreover, the compiler on the AS/400 took advantage of this setup to make the programs run much more efficiently under normal conditions as well.

- For our purposes the big advantage of the AS/400 was that BASIC programs on the AS/400 were compiled, not interpreted. This meant that we could externalize routines that were performed by many programs, and one program could call several other programs that could run simultaneously as “batch” jobs without tying up any terminals. These were huge advantages.

- The BASIC interpreter that was invaluable for debugging was NOT eliminated.

- The AS/400 operating system was designed to be able to take advantage of future hardware advances. Because potential customers were more concerned about solving their immediate problems, this was not a great selling feature. However, it was definitely a great “keeping” feature. Ever program that we wrote in 1988 still works on hardware marketed by IBM thirty-one years later!

- The first announcement did not require this, but eventually every AS/400 came with a 1/4” cartridge tape drive. This eliminated the nightmare of having to convert repeatedly from one storage means to another.

- Priority could easily be assigned to certain jobs.

- A modem could be attached for faxing. Our AdDept customers used these for insertion orders until we devised a better way of handling them.

- The system could be attached to an Ethernet or Token Ring network.

- IBM’s query tool was a big improvement. We insisted that all of our clients licensed it, and I personally trained at least one employee in its use. That worked fine unless the person who had been trained left the company or was reassigned. We also offered support for designing and helping with queries, but we charged a monthly fee for this service.

- Printing was much more flexible. Even laser printers attached to PC’s could be used for printing reports. I learned PCL, Hewlett-Packard’s printer language, so that I could design customized reports with fonts and simple graphics (borders and the like could be generated on HP printers. This was very popular with our customers.

Although some things continued to frustrate me about the AS/400, I grew to appreciate it more and more. It was not designed for tiny developers like TSI, but it allowed us to produce software with features that went way beyond the capacity of any model of the System/36. By the time that the E models of the AS/400 were released in 1992, the low-end systems represented very good investments for the companies who were interested in TSI’s products and services.

On the other hand, IBM’s approach meant that independent developers who marketed to the end users directly rather than to IT departments—and there were a lot of us—had to devised a way to survive until IBM provided us with a reasonably priced product. Those four years were very difficult for TSI. The company survived, but the grim reaper’s shadow was on our door quite a few times.

Over the course of twenty-six years, TSI had at least four AS/400’s (or follow-ons. named iSeries or System i) All of them worked spectacularly well. We hardly ever called IBM for either hardware of software support. We purchased or leased all of them at big discounts because we were developers. On the first one, a B10, I prudently scraped together enough cash2 to order the maximum amount of memory and disk. It was adequate for development purposes, but if one of our clients had tried to run its business on it, it would have been embarrassing. For one thing the operating system itself required almost half of the unit’s disk space! Subsequent releases of the OS required much more disk.

Still, we lived with it, and we came through on the other end.

How well did the strategy work for IBM? In 1988 IBM was one of many competitors in the mini-computer market. The others were DEC, Hewlett-Packard, Data General, Wang, and a host of other companies. By the mid-nineties all of the competitors had conceded the entire market for reasonably priced multi-user computers to IBM. All of them except HP went out of business, and even HP (after several mergers) now makes and sells only PC’s and printers. This stunning event went almost unnoticed by most so-called experts. They blamed poor management by these companies for their demise. Were they all stupid? No, the AS/400’s were demonstrably superior.

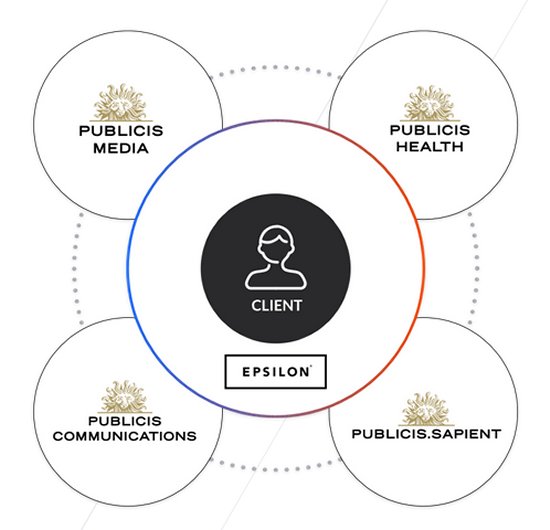

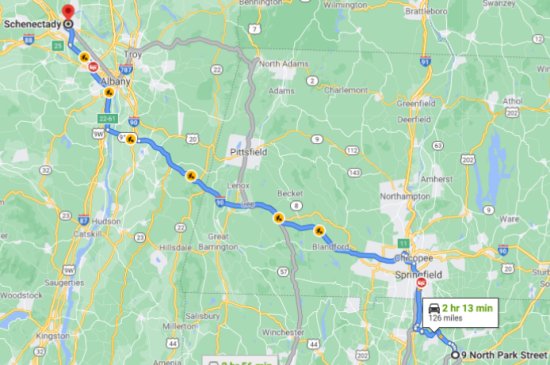

The mini-computer market still exists, but almost no one talks about it, because IBM has hidden its premier product inside hardware with other brands. The only thing that IBM left for the AS/400’s legions of devotees to cling to was the letter i. When Lou Gerstner took over the reins of IBM in 1993, he put a heavy emphasis on services, which were very profitable, over hardware and software, which evidently were not. So, Gerstner never liked the AS/400 approach because the IT departments that used it had little demand for IBM services. For example, at some point in the twenty-first century I visited Macy’s IT department in a suburb of Atlanta. Dozens of IBM employees went to work there every day. One extremely large office contained desks for them and no one else. Macy’s had several AS/400’s or i series systems there. One person managed them all, and he worked for Macy’s, not IBM.

Users of TSI’s software systems loved their AS/400 computers, and they never purchased any services from IBM beyond maintenance contracts.

The AS/400’s operating system (OS/400) employed strict typing of objects. Every object had one and only one type, and it was unchangeable. On a PC a developer—or even an end user—can change the type (as designated by the three-digit “extension” after the period). For example a text file named sample.txt can easily be changed to a comma-separated-values file sample.csv. Users could even make up their own extensions.The operating system might warn the person that changing the extension might make the file unusable by certain applications, but it would still allow it.

The AS/400’s native environment, in contrast, had a limited number of well-defined object types, many of which had equally rigorous subtypes:

- Database files could be physical or logical. A logical file is equivalent to what is called a “view” in SQL.

- Programs had subtypes for each supported language. A new language called CL3 was added.

- Menus were lists of options displayed on the screen, usually with a command line at the bottom. Each option had a number.

- Commands were routines that could be invoked on any command line. A command was essentially a shortcut for calling a CL program.

- The names of the commands supplied by the operating system. were consistent throughout: VVVAAANNN, where VVV was a three-character abbreviation of a verb, AAA was an optional three-character abbreviation of an adjective, and NNN was a three-character noun. For example, DSPSYSVAL was the command for Display (DSP) System (SYS) Value (VAL).

- Most commands had parameters. For example, the GO command required the name of a menu object as a parameter. GO BACKUP caused the system to display and execute the menu object named BACKUP. Pressing F4 after keying in the command displayed a data entry screen for all of the parameters.

- TSI created a large number of commands in

- Several other object types, such as line descriptions and spool queues, were used by the system software. Most system objects of all types (except commands) began with the letter Q.

- BLOBs were objects that did not fit any of the other types. They included all types of images, video, sound, etc. They were added in later releases.

Users could not create new object types or subtypes, but new ones often appeared in new releases of the operating system.

Every object had a name, which was limited to only ten characters. A letter was required for the first character. The other characters could be letters or numbers. A few special characters were also allowed. The names were NOT case-sensitive.

Every object resided in a library, which was itself and object with a ten-character name. This was a departure from the S/36, where data files were not assigned to libraries. On the AS/400 two objects in the same library could not have the same name.

On the S/36 and for a short time in the S/36 environment on the AS/400 TSI used periods in the names files that were associated. For example, files that began with “M.” in the GrandAd system were media files. In the native environment of the AS/400 such files caused a problem for some third-party programs that users might wish to employ to create customized reports. So, TSI changed the names so that the first one or two characters served to group files.

Third-party programs and programs written in other languages also had difficulty with integers that were left-padded with blanks4, as BASIC programs have always done. TSI changed all of its programs to pad integers with zeroes instead of blanks. So, when the value of a three-digit number was 15, it was written on the AS/400 database as 015, not (blank)15.

1. The terms mini-computer and midrange computer referred to multi-user systems that were not powerful enough to run the business applications of major corporations. The System/36 and System/38 were certainly mini-computers. At its introduction so was the AS/400. The twenty-first century models, however, were more powerful than the mainframes of the eighties.

2. I suspect that TSI actually leased it.

3. CL stood for Control Language. CL was the easiest language ever. It was simply a list of commands to be executed in order. Since CL programs were compiled, they could be called from other programs written in any language.

4. I considered this an intolerable bug in the software developed and marketed by the other company. I encouraged the person trying to use the software to complain to whomever claimed that the product would work on AS/400 files. Eventually, we changed our files and programs to forestall a brouhaha.